Search

Recent comments

- struth....

2 hours 16 min ago - earth....

2 hours 56 min ago - sordid....

3 hours 19 min ago - distraction....

3 hours 37 min ago - F word....

4 hours 39 min ago - not losing....

9 hours 51 min ago - herzog BS....

10 hours 14 min ago - freedom to say.....

13 hours 10 min ago - wanton barbarism....

1 day 2 hours ago - little nazi....

1 day 4 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

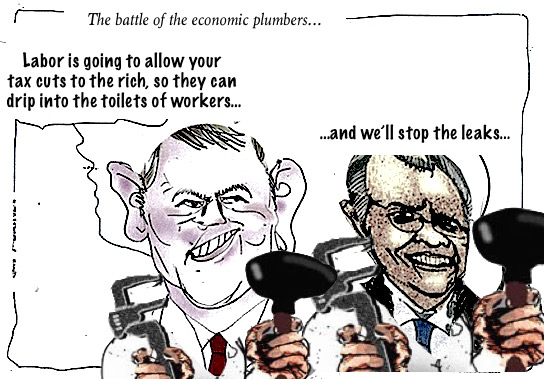

bourgeois plumbers

plumbers

plumbers

The Labor Party has decided to support the government’s tax cuts for the rich. Worth an estimated $184 billion over ten years, Labor politicians are confident that this massive concession to billionaires, whose wealth has doubled during the pandemic, is in the interests of the poor and downtrodden.

It’s a step towards greater fairness and equality. So is the ALP’s decision to ditch its own modest proposal to reduce the negative gearing tax give-away to the well-off.

How can that be?

Well, according to the logic of Labor politics, the highest good is winning office and, by definition, ALP governments benefit everyone. The right wing of the party is clearest about this. But it’s also the position of the left, combined with a dose of handwringing or tissue shredding over the sacrifices of principle—the constant concessions to the rich—that must be made to achieve the higher good.

Understanding politics would be much easier if there were a simpler match-up between parties and social classes: Liberals and Nationals for the bosses, Greens for the middle classes, Labor for workers. But its more complicated.

Workers and their dependents are around two-thirds of the Australian population. The conservatives do most straightforwardly express the views of bosses. Some of them play a very active role in the Liberal Party machine. Along with taxpayer subsidies, big business is the main source of funds for both the Liberals and Nationals. And a few capitalists (Malcolm Turnbull, for example) have even been among its prominent parliamentarians. But neither the Liberals nor the Nationals would ever win elections unless significant numbers of workers voted for them.

Greens voters are disproportionately professionals but most of them are white collar workers, like teachers, who sell their ability to work for a wage, have limited control over what they do on the job and no control over other employees.

Labor’s working-class base has declined, but it still exists. Even if most workers no longer vote for the ALP, they are a much larger proportion of its electoral base than they are of the other parliamentary parties. So the most working-class electorates are generally the safest Labor seats.

At least as important, there is a connection between affiliated trade unions and the Labor Party, via the union officials. They control their unions’ delegations to ALP state conferences, play a major role in the extra-parliamentary machine and have been treading the track from union office to parliamentary suite since the party was established in the 1890s.

And for a well over century, Labor has been committed to managing Australian capitalism. In government at state and national levels on many occasions, it has not deviated from that commitment, which is a fundamental aspect of its make-up.

In fact, its links with the working class mean that Labor can sometimes deliver more for the capitalist class than the conservative parties. The decline in workers’ living standards under John Curtin’s government during World War Two, the introduction of real-pay-cutting wage indexation under Gough Whitlam and likewise Bob Hawke and Paul Keating’s Prices and Incomes Accord, which also reduced real wages and conditions and intensified work, are examples.

Of late, Labor has been complaining about rising government debt. “Deficits as far as the eye can see”, whinged Shadow Treasurer Jim Chalmers in May. Fearmongering about deficits is one of the conservatives’ justifications for cutting public services. At that time, Chalmers was critical of tax cuts for the rich. But he didn’t call for higher taxes on companies and the wealthy to increase the social wage while reducing the deficit.

The ALP’s tax policies have followed the same pattern. Curtin imposed national income tax on workers for the first time. The Hawke-Keating era (1983-96) saw cuts in company tax rates. Labor has been complicit in the decline in the top marginal rate of tax, imposed on people with high incomes, from 75 per cent in 1952 to 37 per cent today.

Now Labor has climbed on board the give-aways-to-the-rich wagon and agreed to a further drop to 30 per cent in 2024—which will be more than $17 billion a year lost to government revenues. Chalmers has done a backflip, justified by the need to avoid a scare campaign over taxes against the ALP in the next federal election.

Labor’s devotion to “fiscal responsibility” has meant that the first backflip is being followed by more, at the expense of workers and the poor. To keep the deficit down, given the tax cut, spending will have to be slashed. According to the Sydney Morning Herald, the party will start by dropping its promises to pay for pensioners’ cancer treatment and dental care.

Read more:

https://redflag.org.au/article/labors-plan-help-workers-handing-rich-184...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 1 Aug 2021 - 6:58am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

of dumb voters...

It’s hard to imagine circumstances in which the federal Labor Party could have made a greater hash of its high altitude, tax policy backflip.

The only thing they got right was to time it to coincide with the nation-stopping Tokyo Gold medal by swimming sensation Ariarne Titmus. Still, that just added to the appearance this was politics over policy for anyone paying attention.

On Monday Labor dropped a decision all close watchers of national affairs had long anticipated and already had crossed off their election bingo cards.

The third tranche of the Morrison Government’s reward-the-rich tax cuts– worth $170 billion over a decade and starting in 2024 – which Labor had already waved through would stay and those dollars in the pockets of high income earners were safe.

At the same time, other 2019 tax policies blamed at least in part for Bill Shorten’s loss would go. Labor was no longer going to remove the concessions on negative gearing of income for owners of existing investment properties or wind back the equally generous capital gains tax discount.

No wonder the Property Council and Housing Industry Association were ordering champagne (click-and-collect, no doubt).

Apart from making vanilla brand talking points about creating “certainty and stability”, Labor barely sought to defend its Gold medal capitulation.

Shadow treasurer Jim Chalmers kept talking about where the focus should be, no doubt hoping to take any focus off what Labor’s shadow cabinet had done.

The preferred focus was “the economic cost of the government failure on vaccines and quarantine and now JobKeeper” and on “what Australia looks like in the future, not in re-prosecuting their last election campaign.”

Policy voidWhat neither Chalmers nor his leader Anthony Albanese talked about was any alternative policy response, despite the shadow cabinet having discussed other options for most of this year.

Top of the list was to leave the top tier tax cuts in place for anyone earning up to $180,000 but imposing a higher rate for higher income earners. This was going to be sold as a one-off, deficit-busting levy, but by this week there was not enough courage in Labor ranks for such a scaled back approach.

If Labor was committed to a positive platform for reform it would be looking at the yawning gap in housing affordability which its negative gearing and capital gains proposals would go some way to mitigating.

As recent polls show, housing affordability remains a hot issue for voters, even in these COVID-obsessed times – three in five Australians agree that young people have no chance of getting into the housing market.

Will Labor do something? Probably. Will it be enough? Most likely not.

This is the hard policy corner in which Labor has put itself. They were always going to be there but now is close to the worst time.

If Labor had thought this through, instead of yet again just seeking to be politically clever, they would have junked the policies on tax and associated high end concessions in the shadows of the last election loss.

Labor lost the election in May, 2019. The party received the wordy but reasonable review of that loss in early November of that year and has really done little in response since then, other than pay the document’s presence occasional lip service.

Albanese, Chalmers and the other architect of those policies that failed, former shadow treasurer Chris Bowen (who continues to be remembered for his “if you don’t like it, don’t vote for us” invitation), should have interred the lot before Christmas 2019.

This would have achieved a couple of things: Labor would have listened and acted in quick time to the public mood (beyond what the branch members might or might not think) and there would have been 18 months of clear air to work out something else to fill the resulting void.

It would have been smart politics, good strategy and prevented the inevitable from looking more political than it might otherwise have appeared.

Too much informationThat needs to be considered. The closer to an election you take what is a fundamentally political decision, the more political it looks. The public do not like guided tours of sausage-making.

This used to be simple, entry level political science. Now it appears beyond the ken of our alternative government.

Of course, the fact these policies were going to be discarded was never really in question. In discussions with caucus members there wasn’t any support for junking negative gearing or dispensing with the capital gains concession, but there was a genuine mood for doing something on housing affordability.

The answer to these questions is the $10 billion, 30,000-dwelling social housing pledge which goes a long way – but not all the way – to meet what is now a decade-long unmet need. This is a very worthy policy but leaves that larger group of middle-Australia, working young families who can’t get into the housing market, any further along.

The other aspect of this week of Dervish-grade spinning by Albanese and his colleagues is its obsession with process. All explanations were mired in the process of getting to this point, how the matter was steered through the party’s formal committees and where this left Labor in the lead up to the election.

That placement in the game schema of the road to the polls was about politics not about policy. It was the process that mattered. The public see through a lot more than they used to – fed by the self serving, echo chamber news feeds of Facebook and YouTube (now the main sources of news for most people). They see the process and they hate it.

If this decision, as inevitable as it was, had been taken 21 months ago, the voters might have forgotten it ever happened.

Read more:

https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/politics/australian-politics/2021/07/31/atkins-labor-policy-backflip/

Read from top.

less tax for the bourgeois?...

Summary

Tax is not just the price we pay to live in a civilised society, it’s the way we shape the civilisation we want to live in. Tax is a powerful tool that can shape our society and as such it is important that we tax the right things at the right amounts.

This paper sets out five principles that will help evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of different taxes. Using this tool will help policy makers determine how to best use taxation to shape their society.

The five principles of a good tax are:

Principle 1 – The tax should minimise the change in behaviour unless it is something that we want less of, in which case it should be effective at changing that behaviour

Principle 2 – The tax should reduce inequality

Principle 3 – The tax should be levelled on those who are best able to pay

Principle 4 – The tax should be simple to comply with, simple to administer and easy to

understand, and

Principle 5 – The tax should be difficult to avoid

The paper uses these five principles to evaluate a number of actual and hypothetical taxes and tax concessions. Each tax and tax concession is rated against each of the five principles. The ratings are:

Yes, it conforms to that principle

It partially conforms to that principle

No, it does not conform to that principle

The taxes and tax concessions evaluated are:

Income tax

Goods and services tax (GST)

Estate duties

Carbon tax

Super profits tax

Buffett rule

Tax concession – GST on food prepared and/or consumed at home

Tax concession – Capital Gains Tax (CGT) discount

Tax concession – Superannuation

Tax concession – Excess franking credits

Read more:

https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Principles-of-a-good-tax-WEB.pdf

See also:

https://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/33609

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!