Search

Recent comments

- though in america....

5 hours 23 min ago - whitewashing....

9 hours 10 sec ago - defenestred....

9 hours 11 min ago - flash floods....

9 hours 22 min ago - still at it.....

9 hours 33 min ago - in the SMH....

9 hours 38 min ago - no-good guest....

9 hours 43 min ago - WAR?......

10 hours 34 min ago - why wait?....

10 hours 48 min ago - still looking....

13 hours 45 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

smugly loosing our history...

archiving

archiving

What should be preserved in national memory? What ought to be allowed to perish and disappear from consciousness?

These questions should be preoccupying the Australian community and legislators right now as the National Archives of Australia appeals for crowdfunding, having been denied $67.7m in the recent federal budget to carry out urgent digitisation of at-risk collection material.

They should. But despite some $30,000 in public donations in response to the unedifying spectacle of the NAA going publicly cap-in-hand, I fear there is every danger the political class will continue to dismiss this issue as the boutique preoccupation of historians and writers. Which it is not.

The national archives is mandated to collect, preserve and if necessary copy records generated by the commonwealth government. It is a broad and daunting ambit, given the amount of material the government creates in its day-to-day business.

But the preservation of the records of how a government does business – and how its decisions impact the lives of citizens – is intrinsic to transparent governance and the service of democracy. The wilful destruction of government records elsewhere has often been a sign of creeping despotism.

When you think of government records, imagine more than paper. For example, the archives hold copies of old ABC television programs, audio recordings of Indigenous witnesses to the royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody, extensive military service records, Asio surveillance footage and non-digitised recordings of famous Australian political speeches. Some of these are under threat due to the archives’ physical and financial incapacity to digitise.

Other items at risk include film of early Australian Antarctic expeditions, audio of the high court native title tribunal and prime minister John Curtin’s wartime speeches. Successive federal governments of both persuasions are responsible for the parlous state of the national archives, and national cultural institutions more generally. They have overseen savage budget cuts (“efficiency dividends”in the more anodyne parlance of Sir Humphrey) to most of them. At the same time, however, they have spent massively to preserve, recall and retell one part of Australian history – that of certain parts of its war service.

Consider this. From 2014 until late 2018 federal and state and territory governments, on conservative estimates, spent some $350m and $150m respectively on commemorating Australian participation in the first world war. This included almost $100m on the needless Sir John Monash Centre at Villers-Bretonneux, on the European western front, where dead Australian servicemen were already respectfully commemorated with countless cemeteries and monuments.

Looked at from another perspective, Australia spent the equivalent of some $8,000–$9,000 commemorating each of its personnel killed in the war. This compares with far lower spending by the United Kingdom ($110m, or $109 on each of its 1.01m dead) or New Zealand ($31m, or $1,713 on each of its 18,100 personnel killed).

Then there is the federal government’s decision to profligately spend $500m to expand the Australian War Memorial so it might display more machines of combat. The federal government never seriously questioned the expansion proposal while Labor, meanwhile, was effectively sucker-punched into supporting it – perhaps because to oppose the unnecessary expansion of the great altar of Anzac is, in Australia, about the highest form of cultural heresy.

As historian and novelist Peter Cochrane has argued, “Drape ‘Anzac’ over an argument and, like a magic cloak, the argument is sacrosanct.” Touché.

It is difficult to accept that the erosion of the national archives – and the financial cuts to the other national institutions – is indicative of anything but an ever-greater militarisation of Australian history and culture.

Of course, $67.7m (the amount a government inquiry identified as requisite to effectively avert a historical disaster at the national archives) is small change in the scheme of government spending – even on memorialisation of things other than Anzac.

Covid-19 undermined planned celebrations last year for the 25th anniversary of James Cook’s east coast continental arrival. But it seems plans to spend some $50m on upgrading the memorial site of his landing at Kurnell are continuing. That’s a lot on one historical episode, as complex and divisive as it is – especially when you consider the NAA is seeking less than $18m more to preserve hundreds upon hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of records of Australian life. There are countless cultural riches that now face imminent extinction.

It is ironic in that context that as part of its remit the national archives have already dedicated considerable resources to digitising and electronically displaying Australian war service records. People all over the world can log on to the NAA website to research their forefathers’ war service records – a practice that reached fever-pitch during the Great War centenary.

Just as there are far more to families than the soldiers who belonged to them, a nation is greater and more complex than its battlefield service. Although the frequency with which our leaders evoke as some singular continuous forge of national character Australia’s commitment to foreign wars from South Africa to Afghanistan, does make you wonder.

The archives can never hope to crowd-save its national treasure.

But as a means of publicly highlighting the cultural vacuity of a government that wants to keep the national narrative simply focused on the present rather than the past (unless it happens to be Anzac, James Cook or Arthur Phillip) it might work quite well.

Conversely, the obdurate will sometimes react by becoming even more so when confronted with their own embarrassing callowness.

Read more:

Read from top

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 29 May 2021 - 8:31pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

loss business as usual...

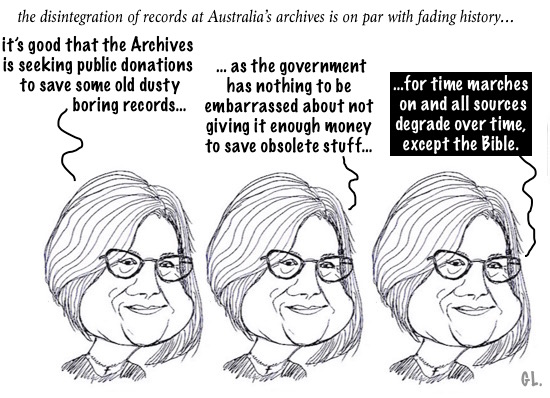

The minister in charge of the National Archives says the institution has to deal with the slow disintegration of its records even as the Archives says parts of Australia’s history will be lost.

Assistant Minister to the Attorney-General Amanda Stoker says it’s good that the Archives is seeking public donations to save records and the government has ‘‘nothing to be embarrassed about’’ in its treatment of the institution.

The Tune review of the Archives, delivered to the government last year but published in March, recommended an urgent $67.7 million seven-year project to digitise the records most at risk. Yet there was no extra money in this month’s budget for the work.

Senator Stoker [cartoon] said the project wasn’t ‘‘something that can be done with the snap of a finger’’ because the Tune review suggested an overhaul of how the government managed records.

National Archives director-general David Fricker told an estimates hearing the institution was making compromises and decisions about what it could save. But Senator Stoker said this was ‘‘business as usual’’.

‘‘Let’s not pretend this is a matter that has cropped up as an isolated incident; it is part of the usual process of the work of the Archives,’’ she told the hearing late on Thursday night. ‘‘Time marches on and all sources degrade over time.’’

Since its plight has been highlighted by the Herald, the Archives has taken in more than $30,000 in public donations and increased its membership tenfold, to 500 people.

Senator Stoker said it was good that the Archives was taking donations because it showed it was implementing a Tune review recommendation that it explore new philanthropic opportunities. ‘‘It’s about buy-in from the public. It’s about public engagement,’’ she said.

Labor senator Kim Carr, who is on the Archives’ advisory council, asked whether that was letting the government off the hook for funding: ‘‘Every other cultural institution in the Commonwealth received support, but not the Archives.’’

Senator Stoker said the Tune review put the Archives in a different position to eight other national institutions, which collectively received $85.4 million in the budget. ‘‘It asks us to turn our minds to what represents an enormous transformation of the way we do archives in this country,’’ she said. ‘‘That necessitates a different approach to putting a few more dollars in the tin.’’

She said the Archives had reached ‘‘a really important moment’’ where the government had to decide whether to fund records in the old way or a new way.

‘‘And when that is done, I think we will all be pleased that we put the money into the new system, rather than continuing to put money into the old system,’’ she said.

But she wouldn’t say when the government would respond to the Tune review or whether that response would include any money.

Mr Fricker said the 115,000 hours of magnetic tape in the Archives’ collection was most at risk of being lost forever because of the time it took to digitise. ‘‘It’s unlikely we’ll be able to preserve it all,’’ he said.

The Herald revealed on Thursday the office of Prince Charles has been made aware of the situation and, in particular, the plight of the Pitcairn Island register, which holds details of the births, deaths and marriages of descendants of the Bounty mutiny in 1789.

The register is disintegrating, along with many other unique archives including wartime speeches of John Curtin and personnel files of RAAF noncommissioned officers from WWII.

Labor’s Raff Ciccone asked Senator Stoker whether it was embarrassing for the government to be attracting this kind of attention: ‘‘This is now starting to become a bit of a joke where you’ve got people from overseas criticising the Commonwealth government, that we can’t even find ... $9.67 million every year,’’ he said.

She replied: ‘‘I don’t think we have anything to be embarrassed about.’’

Source: SMH 29/5/2021

saving history...

Almost 300,000 pieces of Australian history including radio recordings of former prime minister John Curtin and a petition to King George V for Indigenous representation in Federal Parliament will be saved after a $67.7 million funding injection into the National Archives.

The government is facing calls for extra money to protect even more documents, recordings and images as part of an overhaul of an archival system pushed to the brink of collapse by years of funding shortfalls.

After months of revelations in about the plight of the National Archives, the federal government’s expenditure review committee this week signed off on the money to accelerate a program to digitise at-risk documents.

David Fricker, the directorgeneral of the archives, which in May resorted to asking for donations, said it had been overwhelmed by the level of public support over recent weeks. He said that money, plus the government funding, would protect vital pieces of Australian history.

“I’m so happy to be able to report to you tonight that this funding will rescue those records that were at risk of loss,” he told ABC TV.

Assistant Minister to the Attorney-General Amanda Stoker said government money would help protect Australia’s history. ‘‘This funding shows the Morrison government isn’t just committed to protecting the at-risk digital records. It shows we’re prepared to build the capability of the National Archives of Australia to make it a world leader in its operations for decades to come.’’

The Herald revealed in June the money was poised to flow to the archives, which has struggled to protect 384 kilometres of records under the weight of years of funding cuts.

The Tune review of the National Archives, which was delivered to the government last year and released in March, recommended a $67.7 million, seven-year project to urgently digitise the records most at risk.

The money will instead be invested over four years and includes being pushed into enhancing cyber security of the Archives’ collection.

Some of the money will go towards addressing the years-long backlog of applications from historians and students to access particular Commonwealth records and to digitise documents that are vetted for access after requests from the public.

While investing in the shortterm, the government is yet to release its full response to the Tune review, which also recommended the government spend $167. 4 million to help the institution establish a fifth-generation digital archive with state-of-the-art technology and expertise to make sure digital records are properly preserved.

The National Archives has started work but the Tune review says it is not sustainable for it to pay for this out of its existing budget and the government must allocate funds.

The review suggests putting the National Archives in charge of managing information across the entire Commonwealth government to standardise recordkeeping. This would involve 630 records and information management staff from the largest agencies transferring to the National Archives.

Michelle Arrow, the co-editor of History Australia and a former member of the advisory panel for the Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian History, said that the $67.7 million allocation was a welcome response to the issues facing the Archives.

However, she stressed more money would have to be spent to ensure the Archives was able to secure its precious material for future generations.

‘‘The Archives will likely need further injections of funding in order to fulfil its critical role in our democracy. These archives belong to all of us; it is vital that all Australian citizens can access records of government decision-making,’’ she said.

Professor Arrow said even with the extra money, most of the Archives’ material would never be digitised.

Labor’s arts spokesman Tony Burke said the government had been dragged to providing money to the Archives. ‘‘It doesn’t matter whether it’s the Archives, whether it’s our other collecting institutions, or whether it’s something as simple as Australian stories being told on film and TV,’’ he said. ‘‘Every chance the government gets, their first attempt is to trash our history.’’ ’’

Read more: SMH 2/7/2021

Read from top. See toon.