Search

Recent comments

- on earth....

4 hours 19 min ago - distraction....

5 hours 29 min ago - on the brink....

5 hours 39 min ago - witkoff BS....

6 hours 53 min ago - new dump....

18 hours 46 min ago - incoming disaster....

18 hours 53 min ago - olympolitics.....

18 hours 58 min ago - devil and devil....

22 hours 36 min ago - bully don.....

1 day 2 hours ago - impeached?....

1 day 7 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

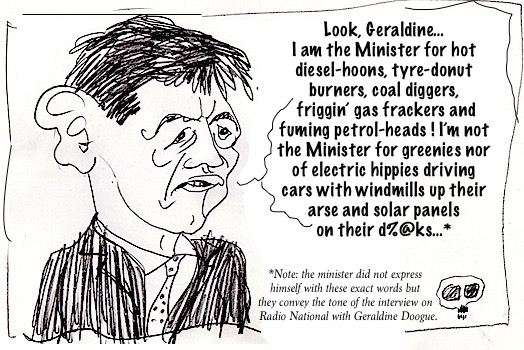

the interview of the day...

Awaiting for the transcripts...

- By Gus Leonisky at 5 Feb 2021 - 2:06pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

a horror movie...

You don’t need severed heads, zombies, vampires or the line “he’s calling from inside the house” to make a horror movie. A slow pan across one Reserve Bank graph will do it, if you understand what that graph means.

Governor Philip Lowe took the National Press Club to Wolf Creek on Wednesday and it seems nobody quite grasped how scary the scenario was in front of them: Years of austerity with negligible economic growth, unemployment as likely to start rising again as falling, with the attendant broken dreams and increased poverty with all that that entails.

Of course, the future painted by Dr Lowe might be a work of fiction – it was all based on the government’s announcements and Treasury’s numbers. There is good reason to hope Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg have been lying about what they intend to do to Australia – or maybe they really do have no flamin’ idea.

Stay with me while I explain how Dr Lowe’s arcane “Government Consolidated Finances” graph is as seemingly innocent and as secretly chilling as a Chucky doll or Norman Bates checking a solo guest into his motel.

For all the upbeat recovery rhetoric from the Prime Minister and Treasurer this week, their actual, on-the-record figures spell serious trouble.

The graph shows it is government policy to reduce GDP growth by 10 per cent over the next three financial years – an average of 3.3 per cent a year.

Just to overcome that drag, private-sector growth would have to be stronger than it has been for nearly all of the past decade.

To post anything like strong economic growth in the years ahead, private sector growth would have to be incandescent – and there’s no rational reason to think it will be –and very good reasons to suspect it will be rather weak.

As the graph shows and Dr Lowe said on Wednesday, government support, most of it federal, amounts to nearly 15 per cent of GDP this financial year. That (plus our moat and health system) is what has given the economy such a quick bounce back from the pandemic plunge.

But the graph then shows the government contribution is cut back by 10 per cent of GDP to just under 5 per cent in 2023-24.

Nothing as radical as that fiscal consolidation (the technical name for austerity) has been attempted in Australia in longer than I can bother to try to find, certainly not in my lifetime.

The graph also shows the reality of what previous governments have managed when trying to rein back big deficits.

The government fiscal stimulus to fight the 2008 GFC was about 5 per cent of GDP.

With the best efforts of governments of both stripes in the subsequent years of “Debt and Deficit” horror headlines, it took nine years to wind back the federal effort to a nearly balanced budget. That’s an average consolidation of only about 0.5 per cent of GDP a year, slower than the two previous consolidations, but it still left the overall economy pretty ordinary.

Even that very slow consolidation proved politically difficult. Rising revenue (thank you, iron ore; thank you, strong migration) eventually did most of the work, rather than any curtailing of government spending.

Peak deficit in the early 90s Keating recession was also close to 5 per cent and the consolidation was much quicker – five years, with an average of about 1 per cent of GDP a year.

And that was very painful for the economy, for Australians. Years of deeply-scarring high unemployment. It was the lessons learned by key policymakers in that recession that resulted in our central bank and Treasury wanting to go hard and fast with stimulus when the GFC hit and to not be in such a hurry to consolidate.

The 80s Howard recession had peak deficit nudging 4 per cent of GDP. The consolidation started more slowly, but then sped up to average close to 1 per cent a year for four years with the help of that decade’s boom.

Thus, over the past four decades, a variety of governments have reckoned the country could only handle consolidation of between a half and one per cent of GDP a year – but we are now being promised a rate more than three times that over the next three years with the implication of yet more of the same beyond that.

The obvious question: Where will very strong offsetting private sector growth come from?

The faith of Mr Morrison and Mr Frydenberg in consumers and businesses champing at the bit to unleash spending and investment is extraordinary – and simply not credible.

As discussed here before, and backed up by Dr Lowe on Wednesday, wages growth is going to be weak throughout these years of austerity. Under current policies, real take-home wages will go backwards. That wipes out hopes for a sustained surge in household consumption.

Business investment was weak before COVID when our economy was on a more stable footing and interest rates and small business tax rates were being cut. The consumer reality and the vague and tardy nature of foreshadowed “stimulus” policy won’t be encouraging much investment beyond the government’s lucky few favourites.

Yet we are being promised unprecedented austerity.

Read more:

https://thenewdaily.com.au/finance/finance-news/2021/02/05/morrison-numbers-frightening-pascoe/