Search

Recent comments

- escalationing....

9 hours 58 min ago - not happy, john....

14 hours 17 min ago - corrupt....

19 hours 39 min ago - laughing....

21 hours 32 min ago - meanwhile....

23 hours 1 min ago - a long day....

1 day 56 min ago - pressure....

1 day 1 hour ago - peer pressure....

1 day 17 hours ago - strike back....

1 day 17 hours ago - israel paid....

1 day 18 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

a pointless and politically-motivated persecution...

The attorney general has been accused of breaching his obligations to the Senate by refusing to properly answer questions on the controversial prosecution of former spy Witness K and his lawyer Bernard Collaery.

The case against Collaery and Witness K is due to first appear in the ACT magistrates court next week, amid continuing protest over what critics see as a pointless and politically-motivated prosecution.

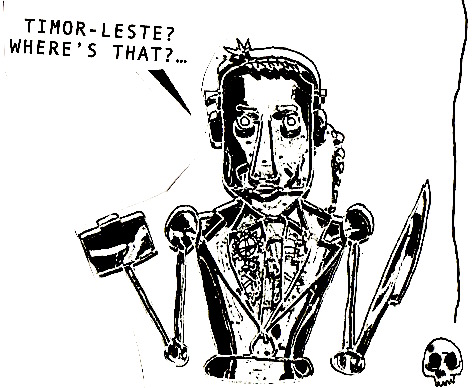

Collaery and Witness K are being prosecuted for their roles in helping to reveal a covert operation mounted by Australian spies against an ally, Timor-Leste, to gain a commercial advantage during sensitive oil and gas negotiations.

Centre Alliance senator Rex Patrick has been one of many championing the cause of Witness K and Collaery, who face up to five years behind bars if convicted.

In early July, Patrick asked a series of detailed questions on notice in the Senate about the prosecution, which was consented to by attorney-general Christian Porter. He asked, among other things, when commonwealth prosecutors began preparing a case against Collaery and Witness K, and on whose instructions. Patrick asked which departments and agencies were consulted, and whether senior intelligence and defence figures were aware or informed of the plan.

Porter’s response this week did little more than confirm the prosecution was occurring, and that he had given his consent. “As the matter is before the court, it would not be appropriate to comment further,” the response said. “Regarding Senator Patrick’s questions relating to alleged Asis activities, it is the long-standing practice of the Australian government not to comment on the operation of our intelligence agencies.”

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/sep/08/attorney-general-...

We should be appalled by Porter. he is unfit to be in his position.

- By Gus Leonisky at 8 Sep 2018 - 3:25pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

australian espionage to rob timor leste...

The Australia–East Timor spying scandal began in 2004 when the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) planted 200 covert listening devices in the Timor-Leste Cabinet Office at Dili, to obtain information in order to ensure Australian interests held the upper hand in negotiations with Timor-Leste over the rich oil and gas fields in the Timor Gap.[1] Even though the Timor-Leste government was unaware of the espionage operation undertaken by Australia, negotiations were hostile. The first Prime Minister of Timor-Leste, Mari Alkatiri, bluntly accused the Howard Government of plundering the oil and gas in the Timor Sea, stating:

"Timor-Leste loses $1 million a day due to Australia's unlawful exploitation of resources in the disputed area. Timor-Leste cannot be deprived of its rights or territory because of a crime."

Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer ironically responded:

"I think they've made a very big mistake thinking that the best way to handle this negotiation is trying to shame Australia, is mounting abuse on our country... accusing us of being bullying and rich and so on, when you consider all we're done for East Timor."

Witness K, a former senior ASIS intelligence officer who led the bugging operation, revealed in 2012 the Australian Government had accessed top-secret Cabinet discussions in Dili and exploited this during negotiations of the Timor Sea Treaty.[3] The treaty was superseded by the signing of the Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS) which restricted further sea claims by Timor-Leste until 2057.[4] Lead negotiator for Timor-Leste, Peter Galbraith, laid-out the motives behind the espionage by ASIS:

"What would be the most valuable thing for Australia to learn is what our bottom line is, what we were prepared to settle for. There's another thing that gives you an advantage, you know what the instructions the prime minister has given to the lead negotiator. And finally, if you're able to eavesdrop you'll know about the divisions within the East Timor delegation and there certainly were divisions, different advice being given, so you might be able to lean on one way or another in the course of the negotiations."

The espionage revealation led to Timor-Leste rejecting the treaty on the Timor Sea, and referring the matter to The Hague. In March 2014, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Australia to stop spying on East Timor.[5] The Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague considered claims by Timor-Leste over the territory until early 2017, when East Timor dropped the case after the Australian Government agreed to renegotiate. In 2018, the parties signed a new agreement which split the profits 80% East Timor, 20% Australia.

Read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australia–East_Timor_spying_scandal

poor fellow our country ...

I wonder when Porter will give us an update into the investigation of "Fishnets" Downer's activities on behalf of Woodside while he was Minister for Foreign Affairs?

They are all unfit to be in their positions Gus ... the basest of creatures all of them.

What kind of country could be proud of such a pissant government?

What kind of people have such little self-respect that they can tolerate such a bunch of carpetbaggers?

one of the richest countries rips off one of the poorest...

As Australia’s Foreign Minister, Senator Marise Payne, makes her first visit to the United Nations General Assembly, Senator Rex Patrick has written to all 193 country delegations to inform them of the prosecution of Witness K and his lawyer for blowing the whistle on the unconscionable and unlawful conduct by Australia’s international spying agency. In 2004 the Australian Secret Intelligence Service spied on East Timor cabinet rooms during purportedly ‘good faith’ negotiations over oil and gas revenue in the Timor Sea.

"As Australia’s Foreign Minister addresses the United Nations General Assembly, delegates need to understand that her government has permitted the persecution of the people who have revealed an illegal operation by one of the world’s richest countries to rip off one of the poorest," said Senator Patrick.

"At the time of the bugging operation, designed to gain advantage in the negotiations, 55 out of every thousand children born in East Timor died before they reached one years of age."

In 2002, in contrast to the rules-based order that Australia often advocates, Australia’s then Foreign Minister, Alexander Downer, withdrew Australia from the maritime boundary jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. The effect of this was that East Timor was rendered unable to claim its rights under international law to the maritime boundary halfway across between the two countries' coastline.

Pressure was put on the then new nation state to agree to a lesser share of the undersea revenue than was its right under international law. The Australian government engaged in a conspiracy to defraud East Timor by spying on their negotiating team.

"The whole thing was a carefully concocted and executed plan, approved by Foreign Minister Downer," said Rex. "I find the whole thing very disturbing."

"I note that senior adviser to Minister Downer when Australia withdrew itself from any international maritime boundary jurisdiction was Mr Josh Frydenberg, now Deputy Leader of Senator Payne’s party. Mr Frydenberg also served as a senior adviser to Prime Minister John Howard when the spying operation occurred back in 2004."

"I further note that when Australia was taken to an arbitral tribunal in The Hague after East Timor became aware of the illegal bugging, the Australian Government sought to fetter the international arbitration by revoking Witness K’s passport immediately prior to his planned appearance at a closed hearing. In essence, Australia thumbed its nose at international law."

"As so often happens in these matters, the heroes of the story are the ones that get prosecuted while the perpetrators get promoted. Delegates at the General Assembly need to understand the duplicity of the Australian Government as it listens to Senator Payne speak."

Senator Patrick is calling for the charges to be dropped. "The laying of these charges are, quite simply, not in the public interest and are profoundly at odds with any sense of justice."

The letter to the delegates can be found here.

Read all:

https://rex.centrealliance.org.au/media/releases/witness-ks-plight-raise...

Read from top.

defrauding the truth under "secrecy act"...

Former attorney-general George Brandis was asked to approve the controversial prosecution of an Australian spy and his lawyer more than two years before consent was finally granted, a document obtained by the ABC has revealed.

The ex-spy, known as "Witness K", and his lawyer Bernard Collaery are facing charges under the Intelligence Services Act 2001 for allegedly conspiring to communicate secret information to Timor-Leste's government sometime between May 2008 and May 2013.

Mr Collaery is also accused of sharing information with ABC journalists about an operation which saw Australia bug Timor-Leste's cabinet room in Dili during negotiations over oil and gas reserves worth an estimated $40 billion.

There has been much speculation about why the Government has suddenly moved to prosecute Witness K and Mr Collaery, almost four-and-a-half years after ASIO raided their homes.

Some such as former Victorian premier Steve Bracks and independent MP Andrew Wilkie have questioned whether it is linked to a recent deal signed over oil and gas, something the Government has emphatically denied.

According to a letter sent to senator Rex Patrick by the current Attorney-General Christian Porter, the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) sent a request for "consent to prosecute" to Mr Brandis on September 17, 2015, more than two-and-a-half years before approval was finally granted.

Read more:

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-10-06/government-sat-on-witness-k-prosec...

Read from top.

para tétum...

Vist Timor for your next holiday... unless the Australian government places you in prison first...

https://www.patreon.com/posts/honest-ad-visit-22364146?

downer should be in the dock for conspiracy

Another important courtroom contest continues in the ACT – the case of Bernard Collaery and Witness K.

Proceedings are still at the procedural stage, even though Collaery – the Canberra lawyer and former ACT attorney-general – and his former client Witness K were charged in the middle of last year with conspiracy to breach the Intelligence Services Act.

By November, the accused still had not received a brief of evidence from the Commonwealth DPP. The whole enterprise has been an extenuated overreach of government power, stretching back to 2013 when the spooks and Constable Plod raided Collaery’s chambers and Witness K’s home.

The case had Christian Porter, the government’s chief awarder of plums to his pals, warning everyone to keep shtum about the case.

Here we are in March and still no decision on whether the trial will be open to the world or a secret court affair. It is understood Collaery’s defence lawyers will be excluded from seeing evidence unless they sign bits of government paper insisting they’ll have to garrotte themselves if they tell anyone what’s going on.

Of course, all this has nothing to do with terrorism but more to do with blowing the whistle on the Howard government’s conduct in spying on Timor-Leste during the negotiations for the Greater Sunrise natural gas deposits.

The case is back before the magistrate on August 6, 7 and 8, with more argument about whether the trial should be open or shut.

Meanwhile, Collaery has finished volume one of his book on Timor-Leste. Volume two, dealing with the government spying operation, will appear after his trial is over. The government has also been issuing threatening letters to Collaery about what may or may not appear in his book.

Many observers are hoping one-time foreign minister, Lord Fishnets Downer, might do a turn in the witness box, preferably not in costume. He’s the man responsible for the overseas spying organisation that bugged the Timor-Leste ministerial offices, who later became an adviser to Woodside, the very oil and gas company that stood to benefit from the seabed negotiations.

Read more:

https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/opinion/diary/2019/03/16/gadfly-quill-shafts-judd/

dark secrecy of our secret courts...

A former intelligence officer who became a secret prisoner after a secret trial has surrendered a medal he earned in the Middle East while fighting Islamic State, saying he has been badly let down by his old employer.

Key points:Witness J, a decorated Duntroon graduate who served 15 years across Australia's sprawling military and intelligence network, had wanted to return the medal in person to the director-general of the agency that employed him.

Denied that opportunity, Witness J instead handed his Operational Service Medal to the ABC, saying it was tainted by his former employer's lack of responsiveness to his mental health crisis.

To protect his identity, Witness J filed off the sides of the medal to remove his name before giving it to the ABC.

"I was proud to be awarded [the medal] but now it signifies to me the failure to discharge a duty of care to me and my other colleagues," Witness J told the ABC.

He was awarded the medal for serving alongside elite special forces soldiers in Iraq during Operation OKRA, Australia's contribution to the Middle East campaign combating Daesh, or Islamic State.

The circumstances of Witness J's treatment by his former employer and the legal system are now the subject of two high-powered independent investigations.

The chief of one of those investigations, James Renwick, has already declared that the unprecedented circumstances of Witness J's case were so extraordinary he "would not like to see [it] happen again".

"There has been an apparently unique set of circumstances whereby a person was charged, arraigned, pleaded guilty, sentenced, and has served his sentence with minimal public knowledge of the details of the crime," Dr Renwick said in his capacity as the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor.

The ABC, which revealed much of Witness J's story in December, has uncovered extraordinary new information about his case.

Witness J, a man in his mid-30s, served in East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan.

But it is when he served in a civilian role in a South-East Asian capital that his troubles began; troubles that culminated in him spending 15 months in prison.

Concerns had been aired back in Canberra about the way he was conducting himself as a single man on an overseas posting.

It was not an ideal time for such a claim to be voiced. Witness J was due to have his security clearance re-evaluated, a process that happens every five or so years in his type of work.

Witness J had been the victim of a drink-spiking incident during in-country language training at the start of his posting, which he had reported.

He had also taken a trip to Singapore during an Easter long weekend with a woman he had met on a language training course, without written approval and with a phone he should not, under departmental policy, have taken out of the country without first notifying Canberra.

Witness J claims he received verbal approval from a senior member at the embassy for his Easter long weekend travel, but that when he later sent a memo back to Canberra to report his trip he omitted mention of the approval, at the insistence of a higher-ranking diplomat.

Witness J's use of smartphone apps to contact diplomatic contacts was also against existing departmental policy, but again he claims this edict was routinely ignored by the many Australians posted to this country.

n late 2017, Witness J was notified that he would be recalled to Canberra as a result of his failure to report the full details of his unauthorised travel over the Easter long weekend.

Shocked that his top security "Positive Vetted" clearance was to be reviewed because of his behaviour, Witness J did what he now lives to regret.

He sent emails of complaint, over an unsecured network, back to Canberra, to the agency's head of security and a departmental psychologist.

In his communications, he named colleagues whose behaviour, he claimed, was more egregious than his own.

One senior colleague, he asserted, was known for his sexual escapades, including paying for prostitutes and strippers.

Witness J claimed the way he had been treated was outrageously hypocritical, insofar as he was being held to a standard higher than his superiors.

Witness J told the ABC that this episode had coincided with a mental health crisis, perhaps triggered by the death of close family members, as much as his service in various combat zones.

But his unwise and unprofessional emails of bitter complaint instantly transformed what might otherwise have been treated as a matter for internal departmental disciplinary process into a matter of criminal offence.

It is claimed Witness J, through his emails — and other communications back to Australia — not only broke strict rules of cyber engagement, but did something worse.

His employer claims Witness J's communications risked identification of foreigners who had been recruited by Australian officers for espionage.

Witness J's communications, over unsecure means, were a concern for intelligence agencies who feared their rivals' cyber capability.

After a secret trial in the ACT Supreme Court, he was sentenced in secret by Justice John Burns to two years and seven months in jail on February 19 last year.

He was released on August 16, after spending 15 months in Canberra's Alexander Maconochie Centre under a pseudonym.

The entire court proceedings were kept closed by an order made under the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act, which prohibited disclosure of the nature of Witness J's offending and the provisions under which he had been charged or convicted.

Attorney-General Christian Porter has said the manner in which the case was wholly suppressed was unprecedented — a circumstance that challenges the principle of open justice, according to Dr Renwick.

"I intend to see whether I can make sensible, practical recommendations that, in a future case, where there might be an intention to have everything in secret, there can be at least some public notice and therefore some media involvement," he told a parliamentary committee last week.

The Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security, Margaret Stone, is expected to report on Witness J's case in the coming weeks.

Witness J said his extraordinary tale might never have been one to tell, had his former agency not failed him at a time of need.

"Three times I asked for mental health assistance and I was denied it. I was working overseas, I needed help and it … it never came," he told the ABC.

"I'm absolutely convinced that if I'd received help, none of this would have eventuated."

As for the medal he has surrendered, Witness J said: "On Anzac Day, I will be proudly wearing the medals I earned during my military service, but I will never wear that one again."

Read from top.

Please remember that Daesh was a Wahhabi/Sunni terrorist organisation set up by the USA and Saudi Arabia via some "moderate rebels" to destroy the Assad "regime" — and disrupt the Shiite government in Iraq — but Daesh (IS, ISIS, ISIL) got out of hand somewhat... Daesh also gave a reason for the US army to stay in Iraq as well as presently STEALING THE OIL in Syria... Think about it. Read all articles on this site about this double-cross set-up.

true or not?...

ISIS is a US-Israeli Creation: Indication #1: ISIS Foreknowledge via Leaked DIA Doc

The DIA (Defense Intelligence Agency) is 1 of 16 US military intelligence agencies. According to a leaked document obtained by Judicial Watch, the DIA wrote on August 12, 2012 that:

“there is the possibility of establishing a declared or undeclared Salafist Principality in eastern Syria (Hasaka and Der Zor), and this is exactly what the supporting powers to the opposition want, in order to isolate the Syrian regime …”

This was written before ISIS came on to the world stage. Clearly ISIS was no random uprising, but rather a carefully groomed and orchestrated controlled opposition group.

The “supporting powers to the opposition” referred to are Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the GCC nations such as Qatar, who are in turn being supported by the US-UK-Israeli axis in their struggle to overthrow Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad. As I outlined in this article Syrian Ground War About to Begin? WW3 Inches Closer, the US is backing the Sunni nations while Russia, China and Iran are backing the Shia nations, so there is the definite potential for this to erupt into World War 3.

Read more: https://www.globalresearch.ca/isis-is-a-us-israeli-creation-top-ten-indications/5518627

-------------------

"The US has created Daesh, and Al-Qaeda."

DISPROOF

The Daesh terrorist group has had various names since it was founded in 1999 by Jordanian anti-American radical Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and first began referring to itself as the Islamic State or Daesh in 2014, when it proclaimed itself a worldwide caliphate. Al-Qaeda emerged in 1988 as a network made up of Islamic extremist, Salafist jihadists and has been immediately designated as a terrorist group by the UN, the EU, the US, Russia and other countries.

see more: https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/the-us-has-created-daesh-and-al-qaeda/

Please note that EUvsDISINFO site is very suspect... and some of its disinfo is actually bullshit. Please note that Al Qaeda and Daesh are TWO SEPARATE networks the Wahhabi ideals of which can be confused at times, but still operate under different command.

-------------------

porter abuses the court system...

Attorney general Christian Porter has been accused of abusing the National Security Information Act after interfering in court proceedings to screen documents held by Woodside Petroleum in a case against barrister Bernard Collaery.

Collaery is before court for his role in exposing Australia’s bugging of Timor-Leste during oil and gas negotiations.

Independent senator Rex Patrick used Senate question time on Wednesday to ask why Porter demanded the federal government have “first access” to documents held by Woodside before they were provided to Collaery.

“How is it possible that an energy company such as Woodside could be in possession of documents that could contain matters related to national security? Or is this simply the attorney further abusing the NSI Act?” Patrick asked.

Read more:

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/aug/26/australias-attorney-general-christian-porter-accused-of-abusing-powers-in-whistleblower-trial

Read from top.

drop it, please!...

Dan Oakes, Witness K and Bernard Collaery

By IAN CUNLIFFE | On 23 October 2020Dear Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions, please demonstrate that the decisions whether or not to prosecute, and the decisions to continue the prosecutions of Collaery and K, are not influenced by possible political advantage, disadvantage or embarrassment to the Government. Please apply the Prosecution Policy to the facts in front of you, uninfluenced by what Porter and the Government so obviously want. Do your lawful duty! Drop the prosecutions!

The very belated but welcome decision by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) that she will not prosecute ABC investigative journalist Dan Oakes for bringing to the public’s attention that their Special Forces military allegedly murdered numerous people in Afghanistan raises important questions.

The CDPP, Ms Sarah McNaughton, has apparently not made any statement in the matter. Rather the Australian Federal Police (AFP) made a fairly opaque statement on 15 October 2020 (reordered here for the sake of clarity):

“The CDPP determined the public interest does not require a prosecution in the particular circumstances of this case. In determining whether the matter should be prosecuted, the CDPP considered a range of public interest factors, including the role of public interest journalism in Australia’s democracy.”

The CDPP’s website includes the “Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth” (the Prosecution Policy). The website says:

“the Policy … underpins all of the decisions made by the CDPP throughout the prosecution process and promotes consistency in decision making. … The Prosecution Policy outlines the relevant factors and considerations which are taken into account when our prosecutors are exercising their discretion. The Prosecution Policy also serves to inform the public and practitioners of the principles which guide the decisions made by the CDPP. … The decision to prosecute must not be influenced by any political advantage or disadvantage to the Government.”

The Prosecution Policy itself, inclusive of attachments, runs to 25 printed pages and more than 13,000 words. What does it tell us?

First, that the pivotal test is whether “the public interest requires a prosecution to be pursued”.

The parts of the Prosecution Policy most relevant to this article follow in italics:

“The decision whether or not to prosecute is the most important step in the prosecution process. A wrong decision to prosecute or, conversely, a wrong decision not to prosecute, both tend to undermine the confidence of the community in the criminal justice system …. the objectives [of fairness and consistency] are of particular importance.”

The Prosecution Policy emphasises that the cost of prosecuting a case is an important consideration: “The resources available for prosecution action are finite and should not be wasted pursuing inappropriate cases.”

A decision whether or not to prosecute must clearly not be influenced by possible political advantage, disadvantage or embarrassment to the Government or on the personal or professional circumstances of those responsible for the prosecution decision.

The Policy lists factors which can properly be taken into account in deciding whether the public interest requires a prosecution. These include:

(a) the seriousness of the alleged offence

(d) the alleged offender’s antecedents and background

(e) the passage of time since the alleged offence

(g) the effect on community harmony and public confidence in the administration of justice

(i) whether the prosecution would be perceived as counter-productive, for example, by bringing the law into disrepute

(k) the prevalence of the alleged offence and the need for deterrence, both personal and general

(l) whether the consequences of any resulting conviction would be unduly harsh and oppressive

(m) whether the alleged offence is of considerable public concern

(q) the likely length and expense of a trial; and

(u) the necessity to maintain public confidence in the rule of law and the administration of justice through the institutions of democratic governance including the Parliament and the Courts.

In the absence of any statement of reasons from the CDPP, we are left to guess at the factors which have led to the decision not to prosecute Dan Oakes. The possible charges were certainly serious in terms of the penalties they carry. They were also matters of high controversy in the community, playing into the widespread concern that the Commonwealth is quick to kill the messenger, but not to punish the person whose guilt is the subject of the message – in this case, special forces who as members of the Australian military allegedly murdered multiple people in Afghanistan. Any criminal case against Oakes would, however, likely have been fairly simple, and accordingly, short.

Collaery, Witness K, and the Prosecution Policy

What does the Oakes decision tell us about the conduct of the prosecution in the cases of Witness K and Bernard Collaery? The prosecution of Oakes will now not commence. Those of K and Collaery are advanced, although apparently still have a long way to run. However, the Prosecution Policy emphasizes that cases should be kept under continuous review: “New evidence or information may become available which makes it no longer appropriate for the prosecution to proceed.”

How do the above factors from the Prosecution Policy apply in the cases of K and Collaery?

They are charged with serious offences.

What of the alleged offender’s antecedents and background? Collaery is a person of impeccable antecedents and background. So apparently is K.

A little oddly, three of the 18 factors which the Prosecution Policy lists seem to overlap: the effect on community harmony and public confidence in the administration of justice; whether the prosecution would be perceived as counter-productive, for example, by bringing the law into disrepute; and the necessity to maintain public confidence in the rule of law and the administration of justice through the institutions of democratic governance including the Parliament and the Courts. I will deal with these three factors together.

All the concern which has been expressed about the K and Collaery cases seems to be that the prosecutions are inappropriate, and of the way they are being conducted and treated – rather than public support being expressed in favour of the prosecutions. Crikey has described the prosecution as a vexatious pursuit of Collaery by Attorney-General Christian Porter. It has reported on “bizarre secrecy orders [sought by the Commonwealth] that would see Collaery prosecuted, with the risk of jail, using documents that neither he nor his legal team, nor the jury, would even be allowed to see”.

As with Oakes, in fact probably more so, there has been a large amount of community consternation that in relation to K and Collaery, the Commonwealth is seeking to kill the messenger, but not to punish the people whose guilt is the subject of the message – in their case, Ministers of the Crown and senior officials who are credibly alleged to have committed very serious criminal offences by planning and authorising illegal bugging of the Timor-Leste Cabinet to gain commercial advantage for Woodside Petroleum. There is widespread belief in the community that the prosecutions of K and Collaery are politically motivated – specifically, to avoid embarrassment to the Government by punishing those who embarrassed it.

A separate but related point is that, in order to prosecute K and Collaery, the prosecution is resorting to approaches which, in the view of many credible and even conservative observers, involve serious attacks on the Rule of Law and on the deeply entrenched Australian tradition of fairness in the conduct of criminal trials. These approaches not only affect the reputation of the Attorney-General, they also bring the Commonwealth DPP into disrepute, and seriously risk also bringing the courts in which the prosecutions are being conducted into disrepute. These matters collectively have a real potential to very seriously and adversely affect community harmony and public confidence in the administration of justice, and to bring the law into disrepute, particularly in a prosecution which is seen by many to be politically motivated. Because of the secrecy of the trials, we know virtually nothing of the obstacles being put in K’s path. We get limited glimpses of what is happening in Collaery’s proceedings. Those glimpses include that the charges against Collaery don’t identify – even to Collaery himself – what secret he is alleged to have disclosed.

Much has been made in Collaery’s case about the enormous risk that his trial will result in serious disclosure of security and intelligence information which will do great harm to Australia. However, the risk that a prosecution will lead to Australia’s national security being put in jeopardy is not a factor explicitly listed in the Prosecution Policy. But surely it is a relevant consideration for the CDPP in deciding whether the prosecution should be discontinued. Justice Mossop said in a recent decision in relation to Collaery that “[w]hen and how that prejudice will occur [in the event that the national security material which will be before the court in the case is disclosed] and how grave it will be is impossible to identify with certainty”.

Another listed factor in the Prosecution Policy is the prevalence of the alleged offence and the need for deterrence, both personal and general. The alleged crimes of K and Collaery arise out of quite unique circumstances – K having been apparently the senior technical person in Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) – who was ordered to do the Timor-Leste bugging operation, and his grave concern when he became aware that the fruits of that bugging were being used to advance the commercial interests of Woodside Petroleum, and that both the then Secretary of the responsible Department (Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)) – Ashton Calvert) and its Minister, Alexander Downer shortly thereafter were put on the Woodside payroll. Calvert became a Director of the company and Downer, when he left Parliament, became a highly paid consultant to Woodside. K sought and was granted permission by the Inspector-General and Security to get legal advice and representation from Collaery in relation to issues arising out of his concerns about what was going on. The “prevalence” of those circumstances would seem to be nil.

Another listed factor is whether the consequences of any resulting conviction would be unduly harsh and oppressive. If found guilty, both K and Collaery are liable to imprisonment. Collaery is 76. K is presumably getting towards the usual retirement age. Both have gone through a personal hell. Will they – should they – be sent to prison?

The likely length and expense of a trial is listed as another factor listed by the Prosecution Policy. Figures released by the Commonwealth at the 12 month mark of the prosecution – at the start of June this year – were that more than $2 million had been spent by the Commonwealth on external legal costs in the prosecutions of K and Collaery. So that figure does not include the time and energies of the CDPP and the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department on the case.

The prosecution of Collaery is nowhere near completed. Indeed, a lot has happened in the four and a half months since the $2 million figure for the cost of external barristers was released. That figure has probably grown to $3 million by now, and will likely double before any jury decision. That represents a very large proportion of CDPP’s external spend each year.

Expense alone would seem to strongly favour the CDPP discontinuing the prosecution of Collaery – and probably also of K. Or is the Prosecution Policy just all words, signifying nothing (to paraphrase the Bard). Do the factors all count for nothing against the obvious determination of Christian Porter – and presumably other Ministers – to punish Collaery and K. Against such determination, does the much touted and statutorily entrenched independence of the Director of Public Prosecutions stand for anything?

As the Prosecution Policy for the Commonwealth emphasizes: “A decision whether or not to prosecute must clearly not be influenced by possible political advantage, disadvantage or embarrassment to the Government”. The CDPP was appointed by the present Government after she came to its apparently favourable attention as Counsel Assisting the highly political Dyson Heydon Royal Commission into trade unions.

I end with a plea: Dear Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions, please demonstrate that the decisions whether or not to prosecute, and the decisions to continue the prosecutions of Collaery and K, are not influenced by possible political advantage, disadvantage or embarrassment to the Government. Please apply the Prosecution Policy to the facts in front of you, uninfluenced by what Porter and the Government so obviously want. Do your lawful duty! Drop the prosecutions!

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/dan-oakes-witness-k-and-bernard-collaery/

Read from top.

state contempt of itself...

The Coalition’s vindictive legal campaign reveals its contempt for democratic rights and shows how easily prosecution can slide into persecution.

By Spencer Zifcak

The criminal prosecution of former ACT attorney-general Bernard Collaery is a perversion of justice. The Morrison government has spent more than $3 million on conducting a case that should never have been initiated. In pursuing the prosecution, Collaery has been brought to the brink of financial ruin. The government’s legal strategy and tactics have been contemptible.

In its flagrant disregard of constitutional and legal principle, the government has abandoned its proper role as a model litigant and damaged the rule of law in Australia. In this article, I consider detrimental aspects of the strategy and tactics to make the point more clearly.

First, a brief reminder of how we have got here. It is well known that in 2004, at then foreign minister Alexander Downer’s behest, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) planted surveillance devices in the Palaco Governo, the building that housed the offices of Timor-Leste’s prime minister and the cabinet conference room.

The purpose of this intelligence-gathering enterprise was to listen in to Timor-Leste’s cabinet deliberations concerning a legal dispute with Australia over the location of the maritime boundary between the two nations. The outcome of that dispute would determine the share of rich oil and gas revenues that Timor-Leste and Australia would receive from prospective drilling in the Timor Sea.

Through this secret surveillance activity, the Australian government obtained crucial information on Timor’s case concerning the maritime boundary before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). This provided it with an unfair advantage in the oil and gas argumentation. In the end, to evade the ICJ’s ultimate judgment, the Australian government withdrew from its jurisdiction.

Witness K had been an ASIS officer involved in the surveillance operation. He had been troubled by it. His reservations were magnified when Downer obtained a highly paid consultancy with Woodside Petroleum, the company responsible for exploiting the oil and gas reserves in the Timor Sea.

Witness K lodged a complaint with the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security concerning the legality of the surveillance. The inspector-general agreed that Witness K could disclose relevant information in any related legal proceedings. Later, information regarding the secret surveillance operation made its way progressively into Australian and Timor-Leste’s media.

In 2013, Timor-Leste sought to re-open proceedings on the maritime boundary issue in the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. It briefed Collaery to represent its interests. Witness K also briefed him to guard against any legal action that may arise from his decision to give evidence before the court. The Australian government put an immediate end to that. It cancelled his passport to prevent him from leaving the country to provide that evidence. His passport has still not been returned.

In the same year, the Australian Federal Police raided Witness K’s and Collaery’s home and office. At Collaery’s office, it uncovered and took a copy of a detailed legal memorandum containing his advice to Timor-Leste’s government on the maritime boundary. It also obtained a copy of Witness K’s draft affidavit prepared as evidence for the Permanent Court.

Things went quiet for five years. Then, late in 2018, out of the blue and for reasons that are unclear, then attorney-general Christian Porter approved the criminal prosecution of Witness K and Collaery. In essence, the allegation was that they had disclosed classified information on the activities of ASIS, contrary to the Commonwealth Intelligence Services Act. Witness K and Collaery believed, with justification, that they acted in the national interest. They took their case — that the Australian government acted unlawfully by secretly tapping the Timor-Leste cabinet and engaging in contractual fraud — to the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

In 2019, Porter made an application to the ACT Supreme Court for parts of Collaery’s trial to be conducted in secret. A secret trial, of course, constitutes a radical attack on the fundamental principles of open justice and fair trial, constituent elements of the rule of law. Justice David Mossop agreed that most of the trial should not be open to the media or the public.

The principal reason Justice Mossop agreed that large parts of the trial should be held in secret was that if Australia’s “Five Eyes” security partners learnt that sensitive intelligence documents were capable of public disclosure in Australia, the trust of our intelligence allies in the security of their own documentation here may be prejudiced.

Looked at abstractly, this was a persuasive argument. It neglected the fact, however, that the documents at the heart of this case were likely to expose government illegality and, possibly, criminal activity. In that circumstance, our security allies would in all likelihood understand that to keep documents disclosing unlawful government behaviour secret would be contrary to Australia’s national interest.

Collaery appealed against the decision to keep substantial segments of the evidence against him secret, and to close most of the hearing of his trial. He argued that to withhold relevant evidence and conduct a secret trial breached a fundamental principle underlying the rule of law: that criminal proceedings should be conducted openly, transparently and fairly.

The appeal was conducted before the Full Court of the ACT Supreme Court in October this year. The court agreed with Collaery. In a summary of its judgment, it accepted that the public disclosure of information relating to the truth of the matters at issue may involve a risk of prejudice to national security. However, quite rightly, it doubted that a significant risk to security would materialise given that the events in question had occurred 17 years earlier.

Furthermore, the court stated that if relevant evidence could not be publicly disclosed, there was a very real risk that public confidence in the administration of justice could be damaged. The court made clear its opinion that the open conduct of criminal trials was important because it deterred political prosecutions, allowed the public to scrutinise the actions of prosecutors and permitted the public to properly assess the conduct of accused persons.

This was clearly a win for Collaery. But critical matters remain related to the conduct of these criminal proceedings that illustrate how easily prosecution can slide into persecution in the face of an ideologically driven administration bent upon secrecy and deterrence.

In the past three years, the government has taken every conceivable step to delay and extend the proceedings. Almost 50 Supreme Court hearings have had to be held to discuss technical, procedural points of law. A trial date is still not in sight. Every Supreme Court hearing has meant that Collaery has been required to pay substantial legal costs. With every hearing, he has become more indebted.

In the judgment of the Full Court it emerged, for the first time, that the government had held back affidavits of evidence that had not yet been provided either to the primary Justice or to Collaery and his legal team. This was a straightforward denial of procedural fairness. The Full Court remitted these affidavits for consideration by the primary Justice to determine whether they contain matter that the government has argued should remain secret. Given the absence of notice, the government should be required to pay the costs.

In recent days it has been suggested in legal circles that the government is procuring even more affidavits sworn by ASIS staff to bolster its argument that the actions of the defendants damaged the agency’s intelligence-gathering capacities. On this matter ASIS staff would hardly be independent or impartial.

Further, it is legitimate to ask why such affidavits will have been submitted so tardily. One suggestion is that by dropping ever more complex and technical evidence upon the court, together with extrapolated legal arguments, the proceedings will be delayed indefinitely.

If, as is likely, the government claims that the new affidavit evidence should also be secret, a single judge will have to review the new material, while Collaery and his legal team will have no access to it. Another plank of the rule of law will have been fractured to Collaery’s detriment.

Perhaps most remarkably of all, the government has submitted that the written judgment of the Full Court of Supreme Court itself should remain secret. So far Collaery has only the one-page summary. In making that submission, the government appears to neither understand nor appreciate that openness and transparency are significant, constituent elements of the rule of law in Australia.

The Collaery case is, perhaps, the most important case ever brought before the Australian courts concerning the extent and limits of freedom of public and political communication in this country. The government’s determination to undermine such fundamental democratic rights is a clear indication that it is willing to act ideologically and illiberally rather in a manner consistent with core principles underlying liberal democracy. Freedom of the press and whistleblower protections are always the first targets of a repressive state.

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/the-contemptible-prosecution-of-bernard-collaery-is-an-assault-on-the-rule-of-law/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!