Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

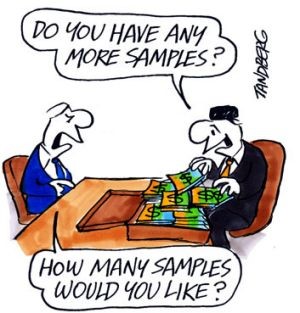

business as usual ...

When arguing against the formation of a Federal ICAC, both major parties have used the reasonable proposition that there are already “multiple levels of integrity and assurance in place at the federal level”.

Except they don’t seem to work.

Take the Securency/Note Printing Australia case.

In 1998, two RBA officials made a secret trip to try to secure a contract with Saddam Hussein to supply polymer banknotes to Iraq. This was highly illegal as Iraq was under strict trade sanctions at the time.

The Reserve Bank firm Note Printing Australia’s plan to make a mint in Iraq was dramatically stopped six months later. Australian diplomats uncovered its dealings with Saddam and warned that NPA’s “informal meeting with Saddam Hussein’s brother-in-law… may have already breached Australia’s obligations under international law”, however no further action was taken.

The illegal Iraq trip was the beginning of an inglorious reign by the directors the Reserve Bank had hand-picked on the boards of its two Melbourne firms.

Over the next ten years, these directors oversaw extremely corruption-prone business practices, tens of millions of tax payer dollars sent to foreign agents, who allegedly used these funds to bribe overseas officials to award lucrative bank-note contracts to the RBA firms. The allegations concern bribery of foreign public officials in Nigeria, Vietnam, Indonesia, Nepal and Malaysia.

The Securency/NPA case was initially rejected without investigation when a whistleblower first approached the AFP in 2008. An investigation began only after the company self-reported wrongdoing to the AFP in the following year after the whistleblower, frustrated by the lack of action, went to the press.

JAMES SHELTON, SENIOR SALES MANAGER, SECURENCY 2007-08: The board didn’t want to know, the AFP didn’t want to know, others I’d spoken to around government didn’t want to know, but they did start to act when it was on the front page of the newspaper.

RICHARD BAKER, AGE INVESTIGATIVE UNIT: The day we published they called the Federal Police in within hours.

In 2011, the AFP finally charged the RBA firms and several executives with bribing officials in Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Nepal in order to secure contracts for the Australian makers of polymer banknotes.

In 2012, the OECD Working Group on Bribery delivered a scathing assessment of how this case was handled.

The Securency/NPA case highlights the potential for miscommunication and a lack of coordination between the AFP and ASIC.

….the AFP stated that it referred the case to ASIC. ASIC stated, that it only considered (and eventually declined) charges against the companies‘ directors for breaches of duties [they did no interviews and no investigation]. It did not consider whether to charge the two companies with false accounting since it believed that the criminal charges against the companies sufficiently captured the alleged misconduct. In addition, the AFP stated that ASIC may give AFP authority to prosecute offences in the Corporations Act but this was not done in the Securency/NPA case. The AFP also charged an individual with false accounting under State laws, but did not do so against the companies. In the end, neither the AFP nor the ASIC considered false accounting charges against Securency or NPA.

In June 2014, the Australian Government through Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade (DFAT) secured suppression orders seeking to protect the identity of various Asian political figures from being named as alleged participants in the Securency bribery scandal. The DFAT notice informing the Court of its application for a suppression order stated that its purpose was “to prevent damage to Australia’s international relations that may be caused by the publication of material that may damage the reputation of specified individuals who are not the subject of charges in these proceedings.” Quite why Australia should be concerned to protect the reputation of Asian-based politicians who can well look after their own reputation (and often do by suing for defamation and using national sedition laws to silence critics) is not entirely clear from the judgment (as the key evidence is redacted).

Wikileaks published the suppression order which lists 17 very high ranking officials (including Presidents and Prime Ministers) from Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia who specifically may not be named in connection with the corruption investigation.

The original suppression orders were made in 2011 on the basis that the former executives of the companies would soon be facing their own criminal trials and that public reporting of the outcome of the cases against Securency and NPA could prejudice jurors.

In 2011, the Malaysian police arrested Abdul Kayum, a Malaysian businessman, arms dealer and agent for both NPA and Securency who was charged with paying bribes to Malaysian central bank bosses, in return for them giving the Reserve Bank of Australia currency printing contracts.

In October 2011 Securency and NPA pled guilty to three charges each of conspiring to bribe foreign public officials and were ordered to pay penalties of $19.8 million and $1.8 million respectively.

By the next year, agents in Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia and Nepal had been arrested and nine former executives from Securency and NPA were facing committal for trial over charges of bribing foreign officials. David Ellery, who was the chief financial officer and secretary of Securency, pled guilty in the Victorian Supreme Court to falsifying accounting for a commission to a Malaysian broker. In return for pleading guilty and agreeing to testify in relation to broader allegations of corruption, Ellery was given a six-month prison sentence, suspended for two years.

In sentencing, Justice Hollingworth said “I also accept that you were acting within the culture which seems to have developed within Securency, whereby staff were discouraged from examining too closely the use of, and payment arrangements for, overseas agents. Secrecy, and a denial of responsibility for wrongdoing, also seem to have been part of the corporate culture at Securency at that time.”

In May 2016 in London, former Securency sales executive Peter Chapman was found guilty of bribing Nigerian mint officials to secure banknote contracts. In sentencing Chapman, Judge Michael Grieve QC remarked that Chapman had been placed under “considerable pressure by your superiors to achieve sales”.

Internal Securency emails revealed heavy pressure from Mr Chapman’s managers to increase polymer sales, including one that said “I would ask you all to focus on those essential markets to see if there are any ways in which we can bring forward orders… creative thinking is required and will be rewarded.”

Despite all this overwhelming evidence, the other executives remain free on bail. The case has been endlessly delayed, in part due to the generous legal insurance policies afforded to several of the defendants courtesy of their senior roles within the RBA’s banknote arms which means they can afford the best lawyers and can initiate their own court actions.

And as for the directors….

Former Reserve Bank deputy governor Graeme Thompson, who is also a former chief of banking regulator APRA, was the Chairman of both Note Printing and Securency. The directors sitting beneath Mr Thompson on the NPA board during this period were former RBA assistant governor Leslie Austin, corporate heavyweight and federal government adviser Dick Warburton, who is also a former RBA board member, and former Liberal Party treasurer Mark Bethwaite. Mr Thompson, Mr Austin and British businessman Bill Lowther are among the directors who oversaw Securency in the period of the alleged offences.

When Thompson was informed by eventual whistleblower Brian Hood that Hood was refusing to provide funds demanded by an agent because he believed they were being used to bribe government officials, Thompson overruled Hood and insisted that the money be handed over. Payments continued even after the agents’ employment had been supposedly terminated.

Mr Hood also revealed that Mr Thompson and other directors, including Mr Bethwaite and Dick Warburton, agreed to conceal from Nepali authorities the secret commissions that NPA had paid to an agent in Nepal.

NICK MCKENZIE, FOUR CORNERS: Graeme Thompson and his fellow directors have walked away from what may be the worst governance failure in recent history.

Under the watch of these now former directors, Reserve Bank firms got into bed with Saddam Hussein, paid an arms dealer in Malaysia millions, covered up corruption here and overseas, and failed to call in the cops when they were told time and time again that their overseas agents were allegedly paying bribes.

While ASIC has refused to investigate them, these directors have gone on to secure prestigious directorships or government posts.

Graeme Thompson is at superannuation giant AMP, Mark Bethwaite’s been appointed to the NSW’s Government’s water catchment authority; Dick Warburton is a director at Westfield and Bob Rankin was given the Reserve Bank’s top European post.

JAMES SHELTON: It seems that they’re a group of people that are untouchable, why I don’t know.

The two whistleblowers lost their jobs.

The whistleblowers lost their jobs while the directors got off scott free

- By John Richardson at 14 Jul 2017 - 4:10pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

9 hours 42 min ago

9 hours 58 min ago

11 hours 44 min ago

12 hours 27 min ago

17 hours 10 min ago

18 hours 27 min ago

19 hours 7 min ago

20 hours 4 min ago

1 day 5 hours ago

1 day 5 hours ago