Search

Recent comments

- culprits.....

2 min 21 sec ago - criminal jew....

35 min 59 sec ago - gestapo....

2 hours 15 min ago - criminal....

2 hours 20 min ago - intensity....

7 hours 46 min ago - adaptation....

8 hours 26 min ago - bloody op.....

19 hours 19 min ago - avoiding biffo....

1 day 1 hour ago - leak....

1 day 3 hours ago - trump's women....

1 day 7 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

now for dessert ...

What does the prime minister stand for, and when will we find out about it?

The mystery of Malcolm Turnbull is the absence of mystery. He is astute, obviously, and eloquent nearly to a fault, but he’s not compelling. To go with his intelligence he has charm, an easy smile and a tone that is not unpleasant, yet for all this radiant self-possession there is not a particle of charisma. He is tough and resilient, but has no apparent gravel in his guts. There was a time when, like Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf, Turnbull “had two natures, a human and a wolfish one”. As prime minister, both natures seem diminished: this smart, likeable and immensely successful man lacks potency and force. All the flair is in the tie. He is bland: in tooth and claw, pale tangerine.

Paul Keating is reported to have told Kevin Rudd in 2008 that Turnbull, the new leader of the Opposition, was brilliant and utterly fearless, and when Rudd asked him for the good news, Keating added that Turnbull had no judgement. That assessment of the Turnbull political prototype seemed to be confirmed when he combined principled policy with practical ineptitude and lost the leadership to Tony Abbott. At that point we might have been tempted to say that the politician Abbott had the judgement that the non-politician Turnbull lacked. But six years later the contest reversed: Abbott was a feckless prime minister, and Turnbull got himself into the job. This time we concluded that the new, temperate Turnbull had returned with the quality of judgement – and patience – he had previously lacked. In this, people saw comparisons with Robert Menzies, and in seeing them they also saw years and years of Turnbull PM.

The Labor Opposition saw much the same writing on the wall and quailed. Our relief was profound upon being set free from Abbott’s unique combination of banalities and freakiness, but today we can recall nothing from Turnbull’s first year except the exhausted managerial buzzwords “agile” and “innovative”, and the observation that there had never been a more exciting time to be an Australian, which sounded like a private-school debating topic and roused about as much general enthusiasm. In an instant we had gone from the Mad Monk’s serial slugfest to the sight of Rumpole declaiming splendidly in the vicinity of the despatch box while, for their palpable lack of enthusiasm, those behind him may as well have been rendered in CGI. That is to say, they seemed not actually there. And nor are we the public there.

This may reflect a broader view of barristers. In court unfathomable and furioso on their client’s behalf, when day is done they walk away (to a harbourside mansion, perhaps) while the client awaits his fate and the bill, and wonders if it might have been as well to make his own case. There are as many theories of leadership as there are styles of leadership to confound them, but a single element is common to all: by one means or another, the leader must bind his or her will to the will of a fair portion of the people. This the prime minister has not done. He has not even bound his will to his party’s.

How could it have happened to Malcolm Turnbull? This is no small fall he’s had. He clings now to a narrow ledge from which, should he dare to look down, he can see only ignominious failure, and this time it will be final. Meanwhile, his opponent, who was believed a year ago to be doomed, is buoyant. Yet Turnbull came into the job with polls to rival Bob Hawke’s in 1983. Much like Hawke, he arrived on a wave of hope, as if dawn had broken and the country was back on a sensible and confident path. If not quite the Great Reconciler, he was the coming man who promised to douse the posturing and rancour with a more consultative style and an intellectual grasp of the way the world is going.

Few politicians have arrived so gently in the job, and with so much goodwill towards them. This time, many folk thought, we will see the real Malcolm, the one who carved right through Sydney’s most powerful and never flinched. Kerry Packer frightened everybody, but he did not frighten Malcolm Turnbull. Packer threatened to kill him, but Malcolm told Packer his aim better be good because if he, Malcolm, got the chance he wouldn’t miss. To read about it in Annabel Crabb’s recent book is to be reminded that Sydney’s corporate circles share elements of their psychology with the late Carl Williams’ (mainly late) circles – or with a schoolyard for that matter.

We are told Malcolm Turnbull is not “bullyable”. It is a fine quality to be sure, but it might make a person see bullies where there are only ABC journalists asking reasonable questions. It might make him thin-skinned. Doubtless his supporters like to see the prime minister accusing Tony Jones of doing Labor’s work, or snapping at Leigh Sales, but to the rest of the public, and to his political enemies of every stripe, it’s a certain sign of weakness – the weakness of a bully, one might say.

He’s lucky he was never interviewed by O’Brien or Lyneham or Carleton in their heydays, as Hawke, Keating and Howard were. Of course he’s not the first politician to round on journalists or unload on media proprietors when they cause him inconvenience, but it has the same effect whoever does it – shouting at the rain is roughly equivalent. And his famous predecessors did have rather more imposing records and bigger pictures to protect.

For months we waited for signs of what Turnbull stood for, some concrete expression of his worldview. So did the Opposition, and then when the fearless beast refused to charge they threw a bit of policy at it and watched in wonder as the PM and his crew reacted as if the thing they had lobbed was a hitherto unknown and probably deadly weapon, and not just a sensible suggestion for dealing with the antisocial consequences of negative gearing. One day everything was “on the table”, the next Labor was said to be proposing measures that would destroy the housing market and thwart the life chances of countless innocent millions. From that moment, Bill Shorten grew and Malcolm Turnbull began to shrink: Shorten because he had put some substance into the debate, Turnbull because he had shied at it and resorted to the sloganeering he’d renounced.

Nothing since has altered the impression that even if Turnbull remains brilliant and fearless he is a very ordinary political leader. As ordinary as his slogan for the most brilliantly conceived and fearlessly executed political miscalculation in modern Australian history, the masterstroke that was intended to consolidate his government’s ascendancy, underwrite his legitimacy and rid the Senate of fringe players, but left him with a one-seat majority, four Hansonites in the Senate, an Opposition in the box seat, and the memory of that barely disguised tantrum that did for a speech on election night. “Growth and jobs” … The sad thing was seeing all the man’s powers reduced to something almost derisory. Sad, because every reasoning person, even those who only reason within their own tribe, would want Malcolm Turnbull and people of similar calibre to succeed in the nation’s politics.

It shows up in the everyday stuff. When Tanya Plibersek last month asked the prime minister why a government bent on savings should spend $170 million on a plebiscite he once opposed (and almost certainly still does), he rose to say with a careworn flourish of his spectacles, “What price democracy?” It might have been a line from Veep – another one. Politics has a way of reducing everyone, including the most brilliant – especially the most brilliant. Decrepit cliché though it was, it did invite us to wonder if we will go to a plebiscite before we go to any future American war. Or before Barnaby Joyce moves another government instrumentality to his electorate to keep a promise he made in an election campaign. The Australian people decided this, Joyce says, which is much less true than it would be to say the Australian people had decided to make same-sex marriage legal if this was what the nation’s parliament decided.

Barnaby Joyce, it’s easy to forget, sits one rung beneath Turnbull in the nation’s political estate. It’s less easy to forget that the prime minister’s blackest enemies sit behind him. But he chose to be where he is and if he remains a mediocre prime minister, or goes rapidly out the door a failed one, it can only be down to him.

Isaiah Berlin reckoned Winston Churchill, for all his excesses and craziness, was carried by his “genuine vision of life”. You could say the same of a Lincoln. And you could add that both of them bound themselves in word and deed to the mythos of their native lands. The last thing we need from our prime minister is imitations of Churchill. But the point is worth making because while Malcolm Turnbull almost certainly has a vision of life, and is attached to his country and its mythology, he projects neither the vision nor the attachments in his politics.

Of course, he will never be a politician in the way Bill Clinton or Paul Keating or John Howard were politicians. He is no pure politician, but he’s been in the game too long now to plead, like the young John Hewson did, that he is not a politician at all and free of the politician’s vices. In his political phase, Hewson was propelled by an almost Messianic faith in neoliberalism, which Turnbull could never share. No fealty to tribe or ideology drives or guides him. He believes in the free market, but who doesn’t? At his more expansive he will talk about opportunities for talent and energy, for partnerships between business and research, his belief in the great potential of Australia. He’s for good governance, free trade, the US alliance. And so is Bill Shorten. So is Sam Dastyari.

It’s no bad thing to come to politics with no larger personal conviction than self-belief, no deeper philosophy than optimism. And it’s essential to make compromises, even big ones, so long as what comes of them is bigger still. But, unlike Menzies (and Howard), Turnbull has no party and no philosophy to truly call his own, and every compromise he makes erodes the ground on which he stands. He looks less like the brilliant and fearless individual, and more like just another trier. Worse than that, he looks like what his enemies want to show him as and what the public suspects he is: a dilettante, a man in politics for his own amusement. The judgement may be unfair, or plain wrong, but it is also wrong to bat away all observations of this kind as “class warfare” or “the politics of envy”. Malcolm Turnbull’s wealth and success would be no handicap were he able to shake off the aura of the arriviste, the man of brilliance and ruthless personal ambition, but without vocation, provenance, attachment or belief.

Just now we wonder not if he will fall, but when. Yet one hope remains to him, and for once it has nothing to do with his own remarkable talents. Turnbull needs what every politician needs and Menzies and Howard had in unnatural abundance. He needs luck. Just one break might grant him time to become a Malcolm Turnbull that the arriviste could never imagine. Two or three lucky breaks might have people calling him a leader; more than that, and we could find ourselves in ten years’ time suffering him as a father figure or even an oracle. Such mutations happen in politics. They are as much to do with us as they are with the politician or whatever causes lucky breaks. This is why his opponents should not take Turnbull’s demise for granted, and be sure to pay for their own entertainment.

The mystery of Malcolm Turnbull

- By John Richardson at 14 Oct 2016 - 11:34pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

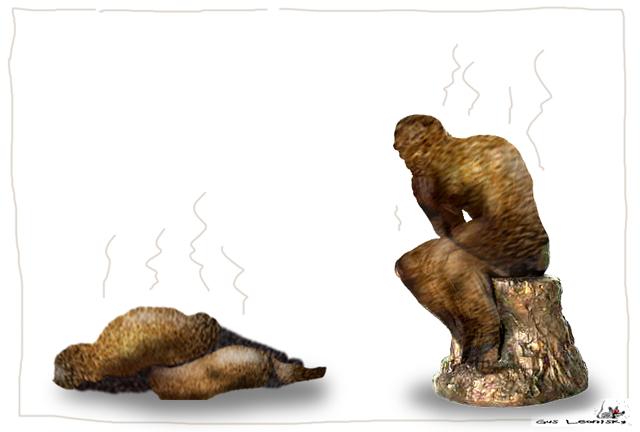

elegant stench...

neo-con, repackaged with elegance...a year of nothing socially important has been achieved by the genius...

Meanwhile at the Castle Hill RSL, the grissle, a couple of dancing bears, the budgie smuggler and Opus Dei go into a bar:

Pull yourself together and for heaven’s sake get out to Castle Hill RSL by 4pm today (October 15) for a Q&A-style performance starring Tony Abbott and two dancing bears from Lord Moloch’s tissues, Chris Kenny and someone named Rita Panahi, who is being shipped in from the starship Herald Sun.

The show is being staged by the god-fearing rump of the NSW Nasty Party, under the baton of the man flogging off the public’s silverware, Finance Minister Dominic Francis Perrottet, and fellow devoted Christian Damien Tudehope MP.

“Sick of the left-wing bias when watching Q&A on a Monday night? Feeling excluded from the public policy conversations which shape and transform our culture and our society?” Well, this is the moment for you.

The chinwag is badged by an outfit called The Policy Forum, “a group of mainstream conservatives” who are devoted to family values, freedom and getting the government out of the road so that insiders can make a quick buck.

The flyer could not be more tempting. “Tony, Rita and Chris are tireless warriors for the conservative cause.” That’s probably a typo for “tiresome”.

Dom Pérignon Perrottet is mentioned in Macquarie Street circles as a future far-right premier of New South Wales, replacing Yes-No Baird, as a creepy, latter-day Captain de Groot.

read more: https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/2016/10/15/gadfly-expert-panel-beaters/14764500003848