Search

Recent comments

- a speech never made....

2 hours 18 min ago - wardonald...

3 hours 51 min ago - MAGA fools

13 hours 11 min ago - the ugliest excuse to go to war.....

23 hours 21 min ago - morons....

1 day 1 hour ago - idiots...

1 day 1 hour ago - no reason....

1 day 2 hours ago - ask claude...

1 day 5 hours ago - dumb blonde....

1 day 13 hours ago - unhealthy USA....

1 day 13 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

why the poor are poor .....

The vast majority of Americans have been the victims of one of the biggest and longest-lasting robberies in history. Danny Katch investigates - and uncovers the culprits.

The tenth richest person in America stood before a private audience in the most expensive town in America and declared that he should one day write a book about ... why the poor are poor in America.

Michael Bloomberg was trying to explain to the exclusive crowd at the Aspen Institute that he had the remedy for why "it's always the poor people who get screwed." But his words rang truer than he intended. During the billionaire's three terms as mayor of New York City, Bloomberg pretty much wrote the book already about how to keep people in poverty.

The Bloomberg era saw the wealth of New York's elites increase astronomically, while the majority of the city's population lived near or below poverty. This is a city whose government posts public service posters about filing for the earned income tax credit, which feature a smiling family beaming that once they get their tax refund, "We're making rent this month."

The New York Daily News reported about homeless people sleeping outdoors during one of the coldest Februarys in city history - within yards of some of the most expensive luxury buildings in the world. The article focused on Deuce, a 50 year old who had found a safe spot in front of a construction site, across the street from a luxury tower where the penthouse apartment just sold for a record $100 million.

The outcome of the article is just as much a sign of the times as the story itself: the next day, the construction company ordered its workers to kick Deuce off the property.

Back in the ski resort town of Aspen, Colorado, Bloomberg rattled off more advice he would give to ordinary New Yorkers: they should drop their college ambitions and focus on becoming waiters in some of the city's many high-end restaurants.

Then he told his audience of fellow wealthy white people that young Blacks and Latinos shouldn't be allowed to own guns: "95 percent of your murders, and murderers, and murder victims fit one ... description. They are male, minorities, 15 to 25 ... the kids think they're getting killed anyways because all of their friends are getting killed. So they just don't have any long-term focus or anything. It's a joke to have a gun, it's a joke to pull the trigger."

The former mayor didn't mention to the Aspen crowd that young Black men in New York City suffer from a 33.5 percent unemployment rate, a catastrophic situation that generates poverty, hopelessness and, yes, violence. Perhaps Bloomberg didn't want facts like these to get in the way of showing off his deep and complex understanding of what life is like on the streets.

There's something else that Michael Bloomberg didn't mention during his Aspen Institute lecture on poverty. During his twelve years as mayor - while most of the city saw its income stagnate or decline--Bloomberg himself quintupled his wealth from $5 billion to more than $25 billion. Two years later, he's up to $35 billion.

We'll see if Bloomberg explains how that happened when he gets around to writing that book.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Rising inequality isn't just a New York story. The richest 400 Americans now have more wealth the entire than bottom 60 percent of the population. In other words, each of these billionaires owns more than almost 500,000 people do collectively. In other words, each of these billionaires owns more than almost 500,000 people - roughly the number of people who live in Atlanta.

Annual income is radically skewed, too. Back in 1980, the country's richest 1 percent took 10 percent of total income. Thirty-five years later, their share of income had more than doubled to 22 percent. If income distribution had remained where it was in 1980 - when the U.S. was already one of the most unequal countries among wealthy nations - the average yearly salary in the U.S. today would be $10,000 more.

And these statistics about income don't even capture the gap in wealth, which comes mostly from investments, rather than wages, and is therefore even more skewed toward the rich.

Almost 25 percent of all the wealth in the country is owned not by the 1 Percent but by the 0.1 Percent - about 300,000 people.

If only one-one-thousandth of the population owns almost one-quarter of the country, how much money does that leave for everyone else

The obvious answer is not so much. Over a third of all adults in the U.S. have a debt in collections reported in their credit files, according to a study by the Urban Institute - with an average of $5,200 being owed. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that there are 369,000 people employed in the debt collection industry.

It's fitting that there's a rough symmetry between the number of people in the 0.1 Percent who own a quarter of the wealth, and the number of people employed to collect debts from the roughly 90 million people who own less than none of it.

So whether measured by income, wealth or debt, inequality in the U.S. is at its highest levels since 1929. That was the final year of the Roaring Twenties, which itself was the final decade of the half-century when modern capitalism was born - a time when a handful of men wrung fortunes out of workers who labored 14 hour factory shifts and permanently indebted farmers.

Today, we call the late 1800s and early 1900s the Gilded Age, after the Mark Twain novel about greed and corruption. Industrialists like John Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie were called "captains of industry" by their admirers - and "robber barons" by their critics. They established charities and built libraries so that future generations like ours would think of them as generous donors, rather than brutal employers who ordered striking workers to be shot dead in places like Homestead, Pennsylvania and Ludlow, Colorado.

The gap between rich and poor is returning to the levels of the Gilded Age. But we're told that things today are different from those bad old days. Rising inequality is portrayed in the media not as a product of class warfare, but as a neutral process that just happens to have resulted from vague impersonal forces like "globalization" and "technology."

Often, the 99 Percent itself is blamed for not having the supposedly numerous well-paying jobs out there for workers with the proper skills and education - even though more Americans than ever before are going to college, and going deeper into debt to do it.

The fact of the matter is this: The rising gap between the rich and the rest of us isn't being caused by mysterious new forces, but by a very old-fashioned one: theft.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The biggest heist in history, committed by the ruling class, has three distinct parts, each employing its own criminal technique. There's the in-your-face mugging - forcing workers' wages down in order increase profits. There's bribery - showering Congress with cash in return for tax cuts for the super-rich. And there's the long con-complicated financial schemes hatched by Wall Street to suck money away from ordinary people's savings.

The most significant of these crimes is the attack on wages. The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) reports that in 2014, wages for most workers stagnated or fell. That finding didn't raise many eyebrows because, as the EPI noted, this has been the case for the past 35 years.

During this same period of time, the rate of productivity - that is how much wealth that workers are producing for their bosses per hour worked - rose by 64 percent.

A Wall Street Journal article last March treated low wages as a mysterious phenomenon that bosses are helpless to prevent. "Stagnant incomes have restrained the American consumer for years," the Journal reported, "creating a vicious circle that has left businesses waiting for stronger spending before they rev up hiring and investment."

In reality, the company that hired more workers than any other has a business model entirely based on stagnant wages.

Walmart, the largest private employer in the country, earned showers of appreciation from the media when it announced last month it would raise pay for its sales associates to a minimum of $9 an hour in April, and $10 an hour in a year's time. If the press were a little less infatuated with the corporate giant, it might have pointed out that the current average wage of $8.81 an hour, according to the union-backed coalition Making Change at Walmart, "translates to annual pay of $15,576, based upon Walmart's full-time status of 34 hours per week. This is significantly below the 2010 federal poverty level of $22,050 for a family of four." Even with the increased minimum pay, associates will fall below the poverty line.

Walmart is vicious alright, but there's nothing circular about the flow of wealth. It goes in a straight line from the workers who create it, up to CEO Mike Duke, who makes $18 million a year, and the six richest members of the Walton family, whose combined net worth is $144 billion.

The second part of the heist is rich people paying lower taxes, both on their personal income--where the rate paid by the richest households on income over about $450,000 for couples has declined from 70 percent in the late 1970s to less than 40 percent today - and on their investments, which is known as the capital gains tax.

Then there are the taxes corporations pay - or rather don't pay. The official tax rate on business profits is 39 percent, but corporations have plenty of money to hire accountants to find loopholes and to bribe/lobby elected officials to grant them exemptions. Thus, economists have another statistic to measure what corporations actually pay. It's called the effective corporate tax rate, and it stands today at 12.6 percent, which is less than the official income tax rate paid by an unmarried Walmart sales associate.

In one stunning example of how "effective" businesses are at not paying taxes, that luxury building in Manhattan with the $100 million penthouse got a $35 million tax break - under a program meant to encourage the construction of affordable housing!

Finally, there's the astronomical growth of the financial industry and the various Wall Street schemes to pocket money under the guise of investing it. The New York Times recently reported that financial advisers are convincing pension funds to put more of their workers' retirement money into private investment plans known as hedge funds, even though these funds make less of a return than traditional stocks.

Hedge funds are an outrageous con: By pocketing 20 percent of all profits - plus 2 percent of all money invested, if the gamble loses - hedge funds have put their owners, not their clients, on the fast track to becoming billionaires. And to top it off, this "success" for the few is put forward as evidence for why ordinary people should trust the hedge funds with even more of their life savings.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

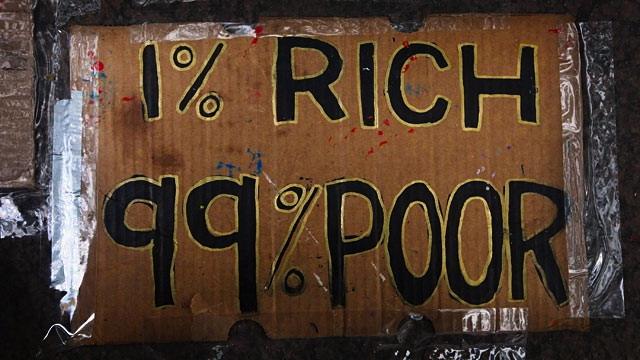

There is a growing awareness about rising inequality, thanks to a series of protest movements beginning with Occupy Wall Street in 2011, which got people talking about the divide between the 1 Percent and the 99 Percent.

Since then, days of strikes and demonstrations by workers at Walmart, McDonalds and other low-wage corporations have brought the Gilded Age-style greed of some of the country's largest corporations into sharper focus. Plus, the rebellion of Black people in Ferguson and the ensuing Black Lives Matter movement has raised the issue not only of police violence, but the overall conditions of racial inequality, 50 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

In response, members of the political establishment who have been in power for years are suddenly noticing the gap between rich and poor. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen declared last October that she was "greatly concerned about growing inequality."

Democrats hope to use inequality as a campaign issue next year, but Republicans are taking up the call, too. A new political action committee launched by presidential hopeful Jeb Bush declares that "While the last eight years have been pretty good ones for top earners, they've been a lost decade for the rest of America."

Even Mitt Romney, who famously described half of the country that wasn't going to vote for him in 2012 as "takers," is getting in on the populist action. "Under President Obama," he said, "the rich have gotten richer, income inequality has gotten worse, and there are more people in poverty than ever before."

Michael Bloomberg, however, is an example of a politician who didn't adjust his rhetoric. For most of his mayoralty, he was admired as someone who was extremely rich and therefore extremely smart. By the end, he was dismissed as an out-of-touch billionaire, and New Yorkers replaced him with Bill de Blasio and his "tale of two cities" campaign against the Bloomberg legacy.

Over a year into the de Blasio era, New York is still a tale of two cities. The new mayor has passed a few small reforms and has a great relationship with some union leaders and community organizations, but he hasn't scratched the surface of redressing the profound theft committed by city elites over the past 40 years.

There's a lesson there for the rest of the country. The remedy for inequality is not empathy, but wealth redistribution, which is not a matter of kindness, but of rectifying a crime.

It's not a coincidence that the last time inequality was this high was 1929. That was the eve of the Great Depression, a period that saw tremendous suffering, but also a wave of workers' struggles - often led by socialists - that won unions for millions of workers and scared the federal government into creating programs such as unemployment insurance and Social Security.

Those victories certainly didn't end the inequality and injustice of capitalism, but they reduced them for half a century. We're going to need those levels of strikes and protests again if we want our generation to write its own story - and take it back from the hands of Michael Bloomberg and his fellow billionaires.

- By John Richardson at 16 Mar 2015 - 1:11pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

tricked into hardship...

MERCANTILISM: SIX CENTURIES OF VILIFYING THE POOR

Add to Reading ListPosted by David Spencer on Sep 18th 2013, 2 Comments

As far as routes to national economic prosperity are concerned the idea that the majority in society must suffer real hardship to achieve such prosperity would seem harsh and unjust. But that is the way that some policy debate in Britain and elsewhere has come to be framed. The idea that the poor must be subject to direct hardship to get them to work and to contribute to wealth creation underlies much welfare reform policy. And the idea that lower wages for the majority will help reduce the budget deficit as well as improve national competitiveness is part of some macroeconomic policy discourse.

Here I want to trace the historical origins of the idea that the poor must remain poor for the nation to grow rich by considering the contribution of mercantilism that dominated economic debates between the 16th and mid-18th centuries. Mercantilism was recently covered in an Economist article though without attention to its darker side in terms of its support for poverty as a basis for a wealthy economy. I want to remedy that neglect here. As I will show below, mercantilism set the basis for the vilification of the “lazy and undeserving poor” that still finds favour today (my more detailed thoughts on mercantilist labour doctrine can be found here). I want to show how such vilification is built on a crude mythology and has no basis in reality. Its persistence 600 years on from the beginning of mercantilism remains a barrier to the formulation of better policy and the creation of a better society.

Mercantilism states that a country will grow richer by increasing its net exports. To achieve this goal, the original mercantilist writers recommended that wages be kept at the subsistence level, not just to minimise the direct cost of labour, but also to maximise the pressure on workers to work. They believed that workers were lazy and had to be coerced to work. Daniel Defoe wrote scathingly in 1704 about the “taint of slothfulness” that was possessed by the labouring class in England, a viewpoint shared by other mercantilist writers. It was observed that as wages increased above the subsistence level workers tended to reduce their work hours and to lower their productivity. This was used by the mercantilists to argue for the maintenance of wages at the subsistence level. Subsistence wages not only helped to make the workforce more productive but also helped to maintain peace and order in society. Thomas Mun’s view, written in 1664, that “penury and want do make a people wise and industrious” summed up the prevailing attitude of his day.

Those who echo mercantilists today may not be quite so shameless in their use of language but the essence of their argument remains the same anti-worker prejudice that is nakedly revealed in earlier mercantilist doctrine.

The original mercantilists were advocates of the “utility of poverty” thesis. They believed that there was a positive side to poverty and that the State should create and maintain poverty as a way to increase the volume of exportable output. Workers were to accept enforced poverty as a necessary foundation for national prosperity. The nation needed a diligent and hard-working workforce but the nation had no duty to pay workers well – on the contrary it was the duty of workers to accept subsistence wages for the sake of the nation.

These views on poverty betrayed the prejudices and lack of sympathy of mercantilist writers. They failed to see how workers’ resistance to work (to the extent that it existed) was linked to the arduousness of work, rather than to any innate character defects in workers themselves. They also missed how workers were unused to a regular pattern of work; forcing workers to work longer hours on a consistent basis went against the traditional pattern of irregular working. Workers resisted work again not out of natural laziness, but out of concern to cling on to older, established patterns of working (see E.P. Thompson, 1967). The mercantilists represented the views of a privileged minority in society and their views distracted attention from the real hardships faced by workers in their lives.

Echoes of mercantilist thinking can be observed in two areas of modern debate. The first is in the area of welfare reform. There is a persistent stigmatising of those on benefits who are seen as “scroungers” living a good life at the expense of tax payers. This mythology fuels a hatred of welfare claimants. Yet, it fails to get to the heart of the life situation of those on benefits which involves genuine struggle and adversity. Looking for work on benefits is hard work and time consuming – it is no paradise state. The myth of the “lazy poor” also distracts from the structural causes of poverty and worklessness and justifies draconian policies that only lead to demoralisation and despair among the poor.

There is also the related argument that higher budget deficits have been caused by excessive welfare spending. Tougher times for the poor via reduced benefits are then seen as key to paying down deficits and getting the unemployed back to work. Apparently, a return to growth requires austerity for the masses. The austerity agenda, however, detracts from the actual causes of the crisis and the associated rise in budget deficits – in particular, the financialisation of the economy that ironically has been associated with the rising income of the very rich. If any group in society should shoulder the burden of responsibility for the crisis and its resolution, it is the reckless rich not the downtrodden poor.

The second area where mercantilist doctrine resonates is in the area of foreign trade. At present, the archetypal mercantilist state is Germany. It has relied on a policy of low wages to increase exports at the expense of other trading nations and the trading surplus that Germany has enjoyed has allowed it to sustain economic growth when other economies have suffered periods of negative or zero growth. Note here that German “success” has been built on the rise of low-paid work. In a modern-day version of mercantilist labour doctrine, workers have been asked to sacrifice income in order to grow the German economy. But Germany now has an unbalanced economy with restrained domestic consumption. Rebalancing towards domestic consumption by the raising of wages has been viewed by critics as vital if Germany is to achieve sustainable growth. But that goes against the spirit of mercantilism as applied in Germany where the achievement and maintenance of low wages has been used to secure a growing economy. Changing economy policy in Germany requires the adoption of a new perspective that does not see low wages as a prerequisite for growth.

Six centuries on from mercantilism, depressingly, we still observe in the media and in politics the routine condemning of the alleged laziness of the poor. We also observe a lack of concern about and acceptance of low wages as a way to restore and increase economic growth. The harsh and unsympathetic attitude towards the poor is not just inhuman but also constitutive of bad economic policy. It is about time we learned different lessons from history.

JOIN PIERIA TODAY!

Keep up to date with the latest thinking on some of the day's biggest issues and get instant access to our members-only features, such as the News Dashboard, Reading List, Bookshelf & Newsletter. It's completely free.http://www.pieria.co.uk/articles/mercantilism_six_centuries_of_vilifying_the_poor