Search

Recent comments

- sicko....

11 hours 11 min ago - brink...

11 hours 27 min ago - gigafactory.....

13 hours 13 min ago - military heat....

13 hours 56 min ago - arseholic....

18 hours 39 min ago - cruelty....

19 hours 56 min ago - japan's gas....

20 hours 36 min ago - peacemonger....

21 hours 33 min ago - see also:

1 day 6 hours ago - calculus....

1 day 6 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

we are made nails for the hammer of government .....

One of the greatest conceits of the modern journalist may be the notion that she, or he, has a better idea of what is in the Australian national security interest or the public interest than the government of the day, the politicians of the day, or even the permanent public administration, including the military and security establishment.

Simple common sense would suggest that this is not true. Particularly in an age when a good deal of the modern media is prostituted towards the ends of particular owners, and a good deal of news judgment is based on what is most likely to attract a click on a computer.

But one of the saving graces, and perversities, of modern civilisation is that the most arrogant and foolish journalist is as likely to be correct on a call about where the national interest lies as the Attorney-General, the judiciary or the national security establishment.

Better access to information, adrenalin, and experience of the experts has not, in practice, led to judgments that will stand up to the test of time. Nor to detachment when it is particularly needed.

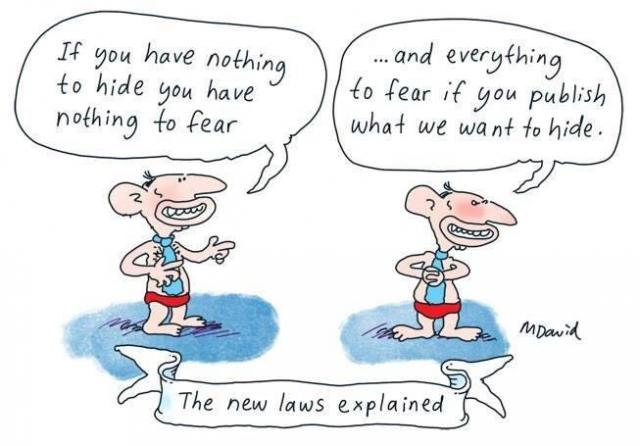

This contradiction does not exist because journalists are more likely to be wise. Or, of itself, because the appointed guardians of the public interest are more foolish. It is because the default setting of the experts - towards secrecy - is actually wrong, most of the time. Sunlight is the best disinfectant for bad ideas. Ideas and actions which cannot stand up once exposed in the sunlight are usually bad ideas in the first place. It may sometimes seem advantageous to use dubious means to justify what seem to be good ends, but only rarely does it achieve much good in practice, in part because of the dubiousness of the means itself. Those most addicted to secrecy are generally covering up.

The Australian public is politically sophisticated, and can tolerate a bit of moral ambiguity when public interest, public safety and national security are involved. But when they have to be protected from the truth - sometimes forever - it is likely that the curtains exist not to protect operations but those who conceived them, usually from the consequences of misjudgment, mismanagement and incompetence.

Australia has secrets that need to be protected. Australian spies, counter-intelligence agents, and people who infiltrate terrorist organisations are involved in important and sensitive work. Their lives could be in peril if their activities were betrayed. But their work represents only the tiniest fraction of the information gathered by the national security system, and a good deal of the emphasis placed on the safety of human spies, informants and infiltrators is being used as a cloak to cover other security operations in no great danger of collapsing were their general nature to be known. Sometimes, indeed, the emphasis on the human is designed to cover not the wide extent of the secret state, but its narrowness and lack of depth.

Others pretend the problem is that journalists might deliberately or inadvertently betray the plans of impending or ongoing military operations, or active intelligence operations such as, say, the rescue of hostages. Somehow, other countries including all of our allies are able to cope, more effectively on the whole, with the risk of betrayal by journalists, including Australians. Indeed, the very limited and deeply slanted information provided by the Australian military establishment has about the topicality and credibility of communist propaganda, and high military fondness for censorship is a significant factor in isolating our professional military from the civilian population.

Nearly 30 years ago, I sat in a two-hour seminar with a former head of the American National Security Agency - a fluent Russian scholar who had been at the centre of the still-unfinished Cold War, and who had known most of the western alliance's deepest secrets since the end of World War II.

He did not think that US government secrecy over any of the things said or done in the interests of the US, or any of its capabilities much still secret, had ever advanced its interests. He could think of many times when it had worked against its interests. Secrecy had meant that some of those who might have poured cold water over intrinsically silly ideas (he instanced the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion) had not been in the know and therefore could not do so.

Secrecy had often prevented people who ought to have known from stopping very morally dubious operations, including CIA assassination programs. Secrecy had often been used to disguise hypocrisy of a very high order - when governments and military or intelligence bodies were saying one thing and doing the opposite, to their ultimate embarrassment and confusion. The objection to that was not necessarily that astute operators were covering both bases, or taking out "insurance policies" against possible events, but that those involved almost inevitably tended to lose sight of their objectives, without any accountability for their actions.

Inevitably, compulsive secrecy became as much focused on cover-up - sometimes of criminal behaviour - and the avoidance of political, bureaucratic or organisational accountability, as often as not for stupidity, failure to take some obvious factor into account or placing too much emphasis on some silly pet theory. He thought highly of the brilliance of many inside the American national security umbrella, but he also thought their thinking and analysis invariably benefited from being open to debate from those outside the umbrella.

He reminded us also that the New York Times had learnt of plans for the Bay of Pigs invasion, and had reluctantly acceded to desperate pleas, some from President John Kennedy himself, to keep mum, at least until the operation was over. The Times gave in, because its editors were afraid of being blamed if the operation were a disaster, as it proved to be. Later Kennedy told editors that he blamed them for listening to him; they should have disclosed, compromised the operation, and saved him and the US from the embarrassment, the humiliation and the lying that followed.

This man's 1980s briefing was in the wake of the Church committee investigations into misadventures and misbehaviour by intelligence agencies, Watergate, the Pentagon papers case (where the Times ignored American government national security pleas) and the comprehensive defeat of American (and Australian) arms and intelligence during the Vietnam War. There have been sundry American military and victories and defeats since, but I have heard or seen nothing which would make me prefer the judgment of George Brandis (or Mark Dreyfus), Tony Abbott (or Bill Shorten) or Angus Campbell (or Duncan Lewis) over his when the national security interest required matters be withheld from the public.

In these days it may be the military which has most discredited the cause, if only by its abject willingness to provide political cover for politicians in operations against boat people. With professionals - as opposed to politicians, from whom one has few expectations - general credibility about where the public interest lies tends to hang on the most dubious proposition supporting secrecy they have ever advanced in public.

One might have depended, once, on ordinary political processes to bring out competing public interests in a debate about secrecy, as with, for example, proposals for a five or 10-year sentence for journalists who ever disclose anything to do with a "special intelligence operation".

It is all too typical of a craven Labor (and yet another reason for judging that, under Shorten, its frontbench is unfit for government) that it dares not say or do anything which might lead Tony Abbott to accuse it of being soft on terrorism. Who cares about the public's right to know, to examine and to criticise?

Yet it is doubtful that the measure will do anything to impose secrecy. Other than to further bring politicians, ASIO and the national security interest into deeper disrepute on such matters.

Does anyone actually believe that it is within the power, even of an all powerful ASIO (or a DSD or NSA) to stop internet disclosure of a security scandal? Can these people do anything more against the next Assange or Snowden than they did against them? All government can do is to clothe such disclosures, and those who make them, in greater appearance of virtue. It is not within the power of a Brandis or an ASIO to impose disgrace. Could a story have better credentials than the knowledge that Duncan Lewis was opposed to its publication?

- By John Richardson at 1 Oct 2014 - 3:53pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

betrayal .....

Jack Waterford’s masterful demolition of the conceit & arrogance of government in attempting to place its interests ahead of those of the lowliest of our citizens is to be applauded.

In reminding us of the slavish endorsement of this corrupt mindset by “Blinky Bill” Shorten & the Labor Party, Waterford elegantly illustrates how far the political class from all sides is willing to go to promote its interests above the collective interests of our nation.

Of course, the fact that we have fools & knaves capable of trying to promote & justify such thinking, like the current Attorney-General George Brandis, should give rise to even greater concerns about the well-being of our democratic institutions, in particular given George Orwell’s thesis that: “If you want to keep a secret, you must also hide it from yourself.”