Search

Recent comments

- 100.....

1 hour 23 min ago - epibatidine....

7 hours 14 min ago - cryptohubs...

8 hours 12 min ago - jackboots....

8 hours 20 min ago - horrid....

8 hours 28 min ago - nothing....

10 hours 52 min ago - daily tally....

12 hours 14 min ago - new tariffs....

14 hours 5 min ago - crummy....

1 day 8 hours ago - RC into A....

1 day 10 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the rocks in his head...

Scores of angry public housing tenants have vented their fury over the decision to sell nearly 300 homes in the heart of Sydney’s historic The Rocks area.

They gathered in the shadow of the Harbour Bridge following the announcement that the properties, many of them heritage listed, would be sold off and more than 400 residents relocated.

“We are not moving one iota,” said Colin Tooher, whose family had lived at the same Millers Point address for six generations.

“Think about it, Barry, and think about it bloody hard,” he said, referring to the New South Wales premier, Barry O’Farrell.

Tooher said he had only learned he would be turfed out within two years after Wednesday morning’s announcement.

The community services minister, Pru Goward, said the cost of rent subsidies and maintaining the properties, which included the brutalist-style Sirius building, had become too high.

She said the money from the sale of the buildings would be ploughed into the public housing system across NSW.

“I cannot look taxpayers in NSW in the eye, I cannot look other public housing tenants in the eye and I cannot look the 57,000 people on the waiting list in the eye when we preside over such an unfair distribution of subsidies,” Goward said.

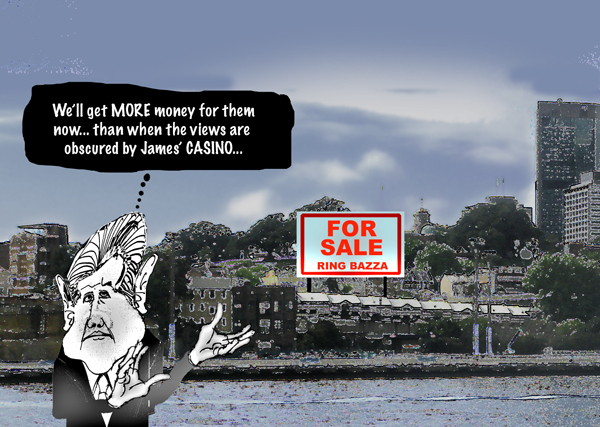

Sydney’s lord mayor, Clover Moore, believed the decision to sell housing stock around the Rocks had been influenced by the billion-dollar development at nearby Barangaroo.

“I think the announcement that has been made by the minister is shocking and I think the manner in which she is carrying it out is cruel,” Moore said.

Too high?.... What a lot of rot... Guess what... The only people who could buy this kind of real estate are LOADED LIBERAL, DEVELOPERS and/or friends of the CONservative NSW government... I can see some horse trading here as well... Some people buying at a price then reselling for double the money in a jiffy... Rorts? Obviously...

Cone on Bazza, don't become a philistine idiot...

- By Gus Leonisky at 20 Mar 2014 - 10:58am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Sydney's old larrikin soul ...

Mr Gardner, who was born in High Street in the house next door to the one he now occupies, says he spent years working, paying taxes and rent. ''It's the only place I've ever known, this is where I grew up, this is my life.''

He says he and neighbours will fight to stay, locking arms and legs if necessary to defy whoever is sent to evict them.

''It will be a fight because we will have many many supporters; we don't want violence, But we are prepared to go to jail.''

For all the brave talk, the forces of global capital are quietly and inexorably at work. The Barangaroo development is fast taking shape across the road from Mr Gardner's house. Down on the next street, tell-tale signs of gentrification are already there: smart cafes on street corners, architects' studios and art galleries where once there were working-class slums for dock-workers and their families.

Besides worrying about where they will be sent, the Millers Point public housing residents say the area will lose its unique neighbourhood character if it becomes the sole preserve of wealthy elites. Here, if anywhere, the last vestiges of Sydney's old larrikin soul reside.

''History isn't just the houses,'' says Terry Tooher, whose husband Colin represents the last of six generations of his family to grow up here. ''It's people. When we tell tourists how long our families have been here, they are fascinated. There will be no one left to tell that.''

Mr Tooher, like Mr Gardner, says ''no one wanted to know about this place when I was growing up''.

Read more: http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/residents-determined-to-fight-decisions-to-sell-housing-at-millers-point-20140319-352we.html#ixzz2wSb9oVbd

bazza's social cleansing...

The O’Farrell government has decided to rob from the poor to give to the rich.

In a city with a growing problem of housing affordability, Wednesday’s decision to sell off 293 homes in Millers Point is a heavy blow – and not just to the 400 plus residents who will be evicted.

One of the blocks of apartments being sold was built in the 1980s. It no more needs to be sold for high-income housing than any of the other apartment blocks in metropolitan Sydney where people in social housing homes live.

All social housing tenants in inner-city properties are now put on notice. If the value of your home goes up, the government is going to put you out of your home when there’s a dollar to be made.

This is tantamount to social cleansing.

The Millers Point community survived the plague, the depression and war. It is shameful that it is government that will destroy this proud and strong neighbourhood.

For most of the 20th century, state governments and their bureaucracies have purposely neglected the maintenance of these historic homes – proving to be irresponsible and uncaring landlords.

The former NSW Labor government took that neglect further and began using 99-year leases to put social housing in private hands.

Now the current government says the neglect is so bad, and the expense to maintain homes in Millers Point is so great, that it’s time to sell.

In the property development business this tactic is known as “demolition by neglect”, and it’s shocking to see successive governments resort to these tactics.

Sixty properties were left to deteriorate without tenants in Millers Point, despite a desperate need for housing – there are 55,000 people on the waiting list for social housing in NSW

read more: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/20/millers-point-sydney-housing

remembering the rocks — 1963... before the green bans...

From wikipedia...:

Green bans were first conducted in Australia in the 1970s by the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation (BLF). Green bans were never instigated unilaterally by the BLF, all green bans were at the request of, and in support of, residents' groups. The first green ban was put in place to protect Kelly's Bush, the last remaining undeveloped bushland in the Sydney suburb of Hunters Hill. A group of local women who had already appealed to the local council, mayor, and the Premier of New South Wales, approached the BLF for help. The BLF asked the women to call a public meeting, which was attended by 600 residents, and formally asked the BLF to prevent construction on the site. The developer, A V Jennings, announced that they would use non-union labour as strike-breakers. In response, BLF members on other A V Jennings construction projects stopped work. A V Jennings eventually abandoned all plans to develop Kelly's Bush.

The BLF was involved in many more green bans. Not only did the BLF represent all unionised builders' labourers in the construction industry; but the BLF also influenced the opinion of other unionised construction workers, and acted as a political leadership of the construction unions in the era. Forty-two bans were imposed between 1971 and 1974. Green bans helped to protect historic nineteenth century buildings in The Rocks from being demolished to make way for office towers, and prevented the Royal Botanic Gardens from being turned into a carpark for the Sydney Opera House. The BLF stopped conducting green bans in 1974 after the federal leadership under Norm Gallagher dismissed the leaders of the New South Wales branch.

One of the last bans to be removed was to prevent development of Victoria Street in the suburb of Potts Point. This ban involved hundreds of residents, trade union members, and other activists and was successful for a number of years, despite facing a well-connected developer who employed thugs to harass residents.[1][2] Arthur King, the head of the residents' action group, was kidnapped in 1973. It was suspected, though never proved, that the men who kidnapped him had been hired by the property developer, Frank Theeman.[3] The New South Wales Police collaborated with Theeman and his employees during the ban and eventually carried out a forced mass eviction of squatters and residents, which saw squatters barricade themselves in a siege for 2 days.[1][4] The green ban was broken in 1974 when the conservative federal leadership of the BLF, under pressure from New South Wales politicians, dismissed the leaders of the New South Wales branch, and replaced them with more conservative people who did not support the ban.[5]Activists, led by activist, resident, and journalist Juanita Nielsen, then convinced another union, the Water Board Employees Union, to impose a ban which was continued for some time.[6] Nielsen was then kidnapped and murdered in 1975.[1][6] The struggle ended with a stand-off in 1977. The developer had been forced to alter his plans, but the residents had been forced out.[5][7]

Although green bans have been implemented on a number of occasions since the 1970s, they have not been so prevalent, nor so comprehensive in their effect. One estimate of the effect of the BLF's green bans puts the amount of development prevented at A$3 billion between 1971 and 1974 (approximately A$18 billion in 2005 money). [1]

Outcomes and impacts[edit]In February 1973, Jack Mundey coined the term ‘Green Ban’ in order to distinguish between the traditional union ‘Black Bans'. Mundey argued that the term ‘Green Ban’ was more appropriate as they were in defence of the environment.[1] Green Bans saved many vital urban spaces and over 100 buildings were considered by the National Trust to be worthy of preservation.

Another example of a Green Ban in Sydney was the proposed North-Western Expressway that was planned by the Department of Main Roads in the early 1970s. The expressway would have cut through the working class residential areas of Ultimo, Glebe, Annandale, Rozelle and Leichhardt. In July 1972, the Save Lyndhurst Committee requested a Green Ban from the Builders Labourers' Federation to prevent the destruction of historic Lyndhurst (built 1833-1835) in Darghan Street, Glebe. Many battles with police took place, including a confrontation between police and squatters on 18 August 1972. The Federal Labor Whitlam Government purchased the Glebe estate in 1973 from the Anglican Diocese of Glebe to preserve the area. In 1978, the Wran-Labor Government decided to abandon much of the inner-urban expressway link and the 19th century character of Glebe remains intact.[8]

Local legacies : New South Wales[edit]Green Ban influenced local NSW planning structures as well as national planning systems. “The Green ban movement in Sydney and Melbourne of the early 1970s, led by the Builder Labourers Federation, was the most profound external indication of the need for planning reform’.[9] In 1977 an editorial from the Australian quoted “bans were an inevitable result of official attitudes which regarded people as irrelevant factors to development”. He also indicated that the decision making process then was devoid of appropriate involvement by relevant communities and individuals.[10]

During the movement infamous redevelopment projects were discarded or scale down, and the planning reform finally began. The previously confined approach to land use planning, due to a “paradigm meltdown”, started to incorporate concerns from community.[11] On one hand, new historical buildings legislations were founded in the 1970s across several states, and on the other the ground legislation of the current planning system emerged.

National reforms : Australia[edit]The green bans in the 1970s initiated a democratic National and State planning systems in which heritage as well as environmentally significant sites became a part of a development proposal.

Read more: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_ban

now that we've changed premiers, it's time to stop the sale...

Now that we've changed premiers, it's time to stop the sale of the rocks housing commission (see top article)... The sale did not make sense and still does not make sense... Hum... let me rephrase this... Selling these apartments and houses would be — and will be — open for GRAND SCALE CORRUPTION, even with the best transparent deals available... Keep your "eyeses" open...

Read also the article above about "The Rocks"... And thank you again Jack Mundey.

elitist opportunistic greed under the guise of rationalisation

Like many residents of Millers Point, I was raised in a public housing property where I was born in 1963. My first community-based political campaign in the late 1970s, was fighting Sydney City Council, which had decided to sell our council house in Camperdown.

It was a battle that was fundamental to my identity and critical to the person I am today.

My mother had been born in this home in 1936 and was raising me there as a single parent. Her parents had been the first residents in the home after the Alexandra Dwellings estate was built in 1927.

For my family, this was more than just bricks and mortar. It was our home for three generations.

It sat in the centre of a proud working class community, made up of people as firmly anchored in the inner city as my own family.

The sense of community was enhanced by it being something of an island - surrounded by the Children’s Hospital, factories and light industry.

It was our home. We cared for it as though we had built it with our own hands, renovating and painting it at our expense to keep it up to scratch.

Yet the council was, as my worried mother said at the time, treating us with no respect. It was as though we did not matter.

My school friends from Millers Point at St Mary’s Cathedral School, supported our campaign because they understood the importance of security of home and community.

Months of tension and uncertainty followed, until the conservatives lost control of the council to Labor and the sell-off was shelved.

I lived at Camperdown for years afterward as I completed my education.

It remained my mother’s home until she passed away in 2001.

Today about 400 residents of Millers Point facing eviction at the hands of the NSW Liberals are suffering the same apprehension and uncertainty I remember so well.

For many, the first they heard of the government’s plan to sell their homes was a cold-hearted eviction notice slid under the door.

No respect.

The government appears to have made no attempt to weigh the financial gains of a sell-off against the social losses involved in the devastation of a community.

I was pleased to read in The Sydney Morning Herald on Monday that the National Trust is opposing the move because of the heritage value of the buildings at Millers Point.

But heritage is about much more than just buildings.

It’s about people.

Miller’s Point is a community – a living, breathing mixture of people that adds to the diversity of the broader Sydney community.

Successful cities are not disconnected enclaves of privilege and disadvantage. They are diverse. Their people come from a mixture of backgrounds.

The logic that only wealthy people should be able to live at Millers Point is a formula for a divided city based on haves and have-nots.

It also points to further public housing sell-offs in Sydney down the track.

That’s out of line with the values of most Australians who understand that a community is only as good as the way in which it treats its least-advantaged members.

Recently I read in The Sydney Morning Herald an elderly resident of Millers Point quoted as saying: “These people cannot come in and walk all over us and turf us out like we are rubbish’’.

It was as though I heard my own mother’s voice ringing down the years.

More than 800,000 Australians live in social housing, including a quarter of a million in NSW alone.

They matter.

Sydney, we can do better than this.

Read more: http://www.smh.com.au/comment/lessons-for-millers-point-from-anthony-albaneses-mother-20140331-zqozg.html#ixzz307qi0NDC

vale jack mundey...

Veteran Sydney unionist and environmentalist Jack Mundey has died aged 90.

Mr Mundey rose to prominence in the 1970s for his leadership of the Builders Labourers Federation, which was famous for its green bans and credited with stopping several developments at The Rocks.

He died late last night and is survived by his wife Judy.

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-11/jack-mundey-dies-age-90/12233542

Read from top.

the public housing crisis...

by Louise O’Shea

The Victorian government’s announcement of a $5.3 billion investment in social housing, which promises 12,000 new dwellings for people on low incomes, has been enthusiastically welcomed by unions and peak social services agencies. Given there are currently more than 100,000 people waiting for housing in Victoria, and it is the state that spends the least per head of population on public housing, it’s not hard to see why any measure purporting to address this crisis might seem like welcome relief.

But the “Big Housing Build” is no such measure. It instead represents a disastrous new milestone in the privatisation of public housing. “The neoliberal moment for housing” that only further entrenches “the government’s exit from public housing” is how RMIT research fellow at the Centre for Urban Research and public housing activist David Kelly described it on a recent Auspol Snackpod podcast. Fiona Ross, a long-time housing activist with Friends of Public Housing Victoria and a public housing tenant, described it in an interview with Red Flag as “the continuation of the policy of privatisation of public housing, now under the banner of the ‘Big Housing Build’”.

The plan is above all a massive handout to the private sector, motivated, it seems, as much by the desire to stimulate the economy and create jobs as it is by the dire need for secure housing. Importantly, it involves no commitment to creating more public housing, and is likely to lead to a net loss.

A breakdown of the spending package by Kelly with fellow Centre for Urban Research academic Libby Porter cuts through the hype. They have found that of the 12,000 promised new units, only about 8,000 will be social housing, with the rest rented at or close to market rates. The term social housing itself is ambiguous—it was introduced by government as an umbrella term to describe both public and community housing, in part to blur the differences between the two. It is widely interpreted by the public as meaning public housing, but almost universally refers to community housing when used by government.

Of the 8,000 social housing units being created, only about 6,000 will be available to the approximately 100,000 people currently on the priority section of the Victorian Housing Register (the housing waiting list). This is because only a small number of the slated new homes will be public housing; almost all the rest will be owned or run by private community housing providers. Unlike government-run housing, community housing providers are not obliged to rent all their stock to those in need. A significant portion may be rented at market rates or very close to them. Of the remainder, only 75 percent have to be made available to those on the Housing Register. This means a significant proportion of the government’s housing budget goes towards subsidising private rentals and the housing costs of others not on the waiting list, rather than being put towards expanding the accommodation available to those most in need.

This is just one of many private sector handouts contained in the Big Housing Build: $2.14 billion of the $5.3 billion package involves, for example, the direct gift of public land to the private sector, including community housing providers, for development. The government hopes this will generate 5,200 new houses, but it is unclear how much of that will be social housing. Even then, any social housing built on this land, will not be public, but will be run by community housing providers.

In the same vein, the “fast start purchase program”, which the government claims will create 2,600 new social houses at a cost of nearly $1 billion, involves subsidising private developers in exchange for the inclusion of some social housing in current or forthcoming developments. This massive handout of public money is entirely avoidable. As housing activists have been arguing for years, the requirement to include minimum levels of social housing in new developments should not be paid for with public money. It should be a legislated obligation, which developers cannot avoid, as it is in many other comparable countries. Had this happened when the Andrews government was first elected, Victoria’s much touted and highly lucrative residential construction boom could have helped provide more units to people who need them, with relatively little outlay of public money. Instead, it has only exacerbated the shortage.

Finally, $1.38 billion of the $5.3 billion package is being allocated as grants to community housing providers to use as they wish, with the government optimistically claiming this will generate 2,200 new social housing dwellings. But there is absolutely no guarantee of this. As Kelly has elsewhere pointed out, a similar grants program initiated in 2017—the Social Housing Growth Fund—promised more than 2,000 houses within five years, yet, so far, none have been built

Hidden in the detail of the plan is also the destruction of hundreds of existing public housing dwellings. According to Ross, 1,100 public housing dwellings are slated for demolition under the plan. Of those, 436 will be lost as part of the Orwellian-named “renewal” of six public housing estates, a pre-existing privatisation program. They will be replaced by 500 new homes (at a cost of $532 million), leaving a net gain of just 54 houses. And because the 500 new dwellings will be community rather than public housing, the result will be a reduction in the number of genuinely secure homes available to those who need them.

The government’s announcement thus represents a significant milestone in the transition away from government-owned and operated public housing and towards inferior, privately run community housing. “The outcome”, Ross argues, “will be to strip housing stock away from public ownership [and place it] into non-public, commercial ownership. Housing stock owned by the people of Victoria is reduced, while housing stock owned by a tiny elite is massively increased. This is ... being achieved by giving away $5.3 billion of public money”.

Yet the plan has not only escaped criticism from many of those who would ordinarily oppose privatisation; it has been actively celebrated. In large part this reflects the success of the government’s slow-burn, subterranean approach to housing privatisation.

Unlike electricity, public transport or the sale of major public assets like ports, privatisation in the housing sector has been done gradually and largely without raising any alarms. It has involved the gradual transfer of housing stock to private corporations. “Community” housing, as this private form of housing for low income tenants is known, has been expanding rapidly since the early 2000s thanks to this government largesse. In 2008, there were twelve registered community housing agencies managing around 11,000 units. By 2018-19 this had expanded to 39 registered agencies managing 19,694 units. Nationally, the community housing sector operates more than 100,000 properties.

Community housing might sound benign, and the government is keen to play down any difference with public housing, but the reality is it is an inferior form of housing in which tenants have significantly fewer rights.

For one thing, rent is much higher. Public housing tenants pay a fixed 25 percent of their income in rent. If their income is reduced for any reason, so is their rent. Community housing tenants, on the other hand, usually pay 30 percent of their income in rent, and do not necessarily have the right to a reduction in the event of income reduction during their tenancy. On top of this, community housing tenants often also have to pay a service charge that covers basic maintenance and services, most of which are ordinarily covered by rent. If they are eligible for Commonwealth Rent Assistance, this also must all be paid to the community housing provider on top of the rent. Community housing residents can easily end up paying close to half their income to the private housing provider. Public housing tenants also have “a strong framework protecting their human rights”, says Ross. “Community housing does not afford these same protections to tenants ...Feedback from community housing tenants is that company policies are not well explained and can change at any time. Community housing landlords tend to be more punitive than the government. Even with its shortcomings, the state government is a better landlord.”

There is also less of an obligation on community housing providers to take tenants according to need. “Allocation to community housing is not transparent or carefully monitored by an outside independent body to ensure equity of access”, explains Ross. Community housing providers “can cherry-pick prospective tenants and create their own waiting lists from private sources ... [they] are not compelled to house people who are homeless or have been on the waiting list for years”, she says. Those with higher incomes or fewer special needs are more profitable, and therefore more desirable. The government, on the other hand, is obliged to take all its tenants from the Register and then according to urgency of need.

Well-orchestrated government spin has largely disguised this reality. “The privatisation argument continues to be carefully suppressed”, says Ross, “since it is a bipartisan agreement of both Liberal and Labor. Interestingly, when the Liberals were in power, they were more open about calling it privatisation, but Labor wants to avoid the word at all costs ... The media unfortunately has not done in-depth reporting and often confusingly adopts government jargon, which in turn confuses the public. The term ‘not for profit’, for example, belies the fact that the winners of government tenders are huge housing associations, which are certainly profit driven. They plough their surpluses into continuing to further their private empire building”.

Read more:

https://redflag.org.au/node/7480

Read from top...