Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the long goodbye ....

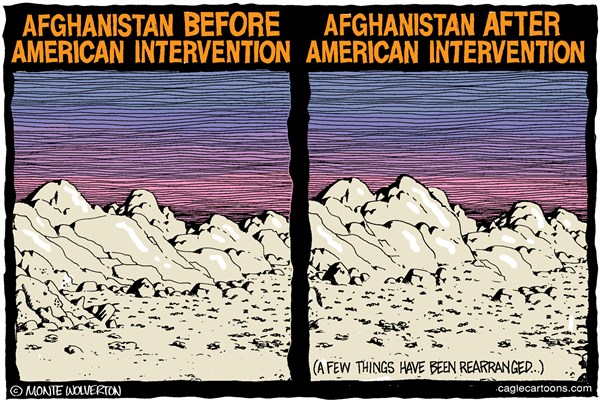

From his first campaign for the White House, President Obama has vowed to end more than a decade of war, bring the troops home and put America on a less militaristic footing. He has reduced the forces in Afghanistan from about 100,000 in 2010 to about 47,000 today and has promised that all American and international combat forces will be out by the end of 2014.

But he has also indicated that a residual force of American troops will remain in Afghanistan to train Afghan security forces and engage in counterterrorism missions. In all this time, he has not made a clear and cogent case for any particular number of troops or explained how a residual force can improve the competency of Afghan forces when a much broader and intensive American engagement over the last decade has not.

Yet last week the Obama administration announced that it had reached an agreement with Afghanistan on a long-term bilateral security arrangement that, officials say, would allow up to 12,000 mostly American troops to be in that country until 2024 and perhaps beyond - without Mr. Obama offering any serious accounting to the American people for maintaining a sizable military commitment there or offering a clue to when, if ever, it might conclude.

The administration’s focus, instead, has been on whether an Afghan tribal council and the Afghan Parliament will formally approve the pact and whether President Hamid Karzai will sign it.

Even now, key details of the security agreement are unclear. Mr. Karzai has spoken about a force of 10,000 to 15,000 American and NATO troops; President Obama has not yet announced a figure, but officials have talked of 8,000 to 12,000.

Officials have said the troops’ main role will be to continue to train and assist the 350,000-member Afghan security force. The capability of the Afghan security force has improved, but it still cannot defend the country even after a $43 billion American investment in weaponry and training. Proponents of a residual force also argue that it is needed to protect Kabul, to prove that the United States is not abandoning Afghanistan and to pressure the Taliban to negotiate a political settlement, which military commanders say is the only path to stability. In addition, since Afghanistan cannot finance its security apparatus, American officials say Congress is unlikely to keep paying for the Afghan Army and police, at a cost that could range from $4 billion to $6 billion per year, unless Americans are there to verify that the money is properly spent.

The American forces are also expected to conduct counterterrorism missions when needed. The draft agreement allows United States Special Operations forces to have leeway to conduct antiterrorism raids on private Afghan homes. As Mr. Obama’s letter to Mr. Karzai says, American troops will be able to carry out the raids only under “extraordinary circumstances involving urgent risk to life and limb of U.S. nationals.” (Under current protocol, Afghan troops take the lead in entering homes.) The pact also gives American soldiers immunity from Afghan prosecution for actions taken in the course of their duties. The failure to reach agreement on this immunity issue blocked a long-term security deal between the United States and Iraq and led to the final withdrawal of troops there.

President Obama said in May that the United States needs to “work with the Afghan government to train security forces, and sustain a counterterrorism force, which ensures that Al Qaeda can never again establish a safe haven to launch attacks against us or our allies.” Managing a productive relationship with Afghanistan has always been difficult with Mr. Karzai, who is an unpredictable, even dangerous reed on which to build a cooperative future. And it is unclear if Afghanistan, driven by corruption, sectarian divisions and the Taliban insurgency can have any better governance when elections are held next April.

Mr. Karzai’s long record of duplicitous behavior is just one of the many reasons it is tempting, after a decade of war and tremendous cost in lives and money, to argue that America should just wash its hands of Afghanistan. There is something unseemly about the United States having to cajole him into a military alliance that is intended to benefit his fragile country.

Regardless of what he, the tribal council and the Afghan Parliament decide, President Obama still has to make a case for the deal to the American people.

- By John Richardson at 25 Nov 2013 - 6:44am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

47 min 10 sec ago

1 hour 17 min ago

2 hours 35 min ago

4 hours 26 min ago

5 hours 49 min ago

6 hours 43 min ago

7 hours 11 min ago

7 hours 9 min ago

11 hours 8 min ago

1 day 4 hours ago