Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

on lamenting ....

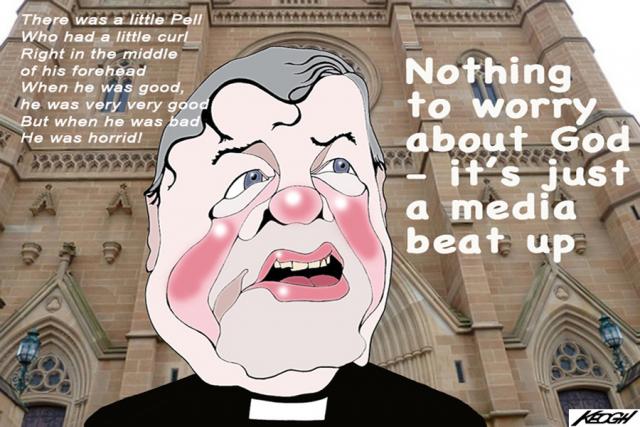

The cardinal’s colour rose all afternoon. He smiled once or twice after negotiating a difficult passage. He clasped and unclasped his hands, never quite in prayer. He droned. He snapped. He stared at the six members of the Victorian parliament’s family and community development committee with a gaze that seemed focused somewhere south of Macquarie Island.

But the former archbishop of Melbourne was in the room. That was the triumph the gallery of victims and the parents of victims was enjoying. They didn’t expect anything new from him – Cardinal Pell is not a man known for changing course – but he was in Melbourne answering questions. He identified his team of advisers. “All of them,” he told the committee, “married people with children, keen to help us with this fight.”

He had many complaints. He complained he hadn’t been called to give evidence months ago; that he wasn’t allowed to make an opening statement; that the church had experienced “25 years of hostility from the press”; that the Victorian government “was not active earlier” on child abuse, and that he was so often misunderstood: “I have always been on the side of the victims.”

No one rose when he came into the room. He was in civvies: white shirt, no jewellery, his head bowed under the weight of the mitre he wasn’t wearing. A fortnight shy of his 72nd birthday, Pell is a big man with strength in reserve. His voice is masculine but oddly refined: Oxford over Ballarat.

Everything about him except his testimony spoke of power. “I am not the Catholic prime minister of Australia,” he assured the committee. He downplayed his authority; his friendship with Benedict XVI, and his influence in Rome and his hold over his fellow bishops. He spoke of the church in Australia as if it were an ungoverned archipelago of parishes and diocese and religious orders.

He admitted his church had covered up abuse for fear of scandal; that his predecessor Archbishop Little had destroyed records, moved paedophile priests from parish to parish and facilitated appalling crimes. He agreed Little’s behavior was reprehensible, not Christlike.

“Did you ever transfer a priest about whom you knew there were allegations of child abuse?” asked pugnacious former journalist and deputy chair of the committee, Frank McGuire.

“I don’t believe I did. I never meant to. I don’t believe I did. And therefore I’m quite happy to say I didn’t.”

“Did you in any way cover up offending?”

“No.”

“Were you guilty of wilful blindness?’’

“I certainly wasn’t.”

But as archbishop of Melbourne he had, he conceded, continued to pay a stipend to Father Ronald Pickering who vanished to England in 1993 after child abuse allegations began to be made. Pickering refused to assist the police, refused to help the church insurers and refused to come back to Melbourne to face the music. But Pell kept paying his “frugal” allowance.

“As long as a priest is a priest,” he explained to the committee, “canon law requires a bishop to support them.” Pell’s successor, Archbishop Denis Hart stopped the payment and initiated an investigation in Pickering’s old parish to see if there were other victims. Pell regretted not having done so himself: “It was far from perfect.”

As the cardinal sees it, the problem is not a culture of abuse in the church but a culture of silence. “I’ve sometimes said, if we’d been gossips – which we weren’t – and we had talked to one another about the problems that were there we would have realised earlier just how widespread this awful business was.”

That was said mid-afternoon. But an hour or so later as the light was failing, Pell faced the last of his interrogators, an angry Catholic barrister, David O’Brien. In a few lethal moments, the National party parliamentarian had the cardinal admitting that the machinery he put in place to deal with abuse when he became archbishop of Melbourne in 1996, involved “no systemic investigation”.

The committee showed no surprise. They had heard the same from Victorian bishops – active and retired – and the heads of religious orders in the state: victims were cared for but there were few, if any, church investigations to find out what was really going on, how bad the problems were.

Over and again the cardinal apologised for the sins of the church and his own failings. He was determined to apologise. But he did not go gently. His is a hard voice to silence. At one point he was explaining the huge amounts of money he had spent on Domus Australia in Rome.

“There is a long tradition of pilgrim houses,” he said. “The Saxons –”

“With respect,” said the committee chair, Georgie Crozier, “I don’t want to hear about the Saxons.”

“I would appreciate the courtesy of you listening,” said Pell, and carried on to his conclusion over all objections.

But money is what it comes down to in the end. The victims want more than apologies and explanations. So, it seems, do the politicians. They want compensation for victims to be set not by the machinery of the church – Pell’s Melbourne Response and the Towards Healing system that operates in the rest of Australia – but by the secular courts.

“I got $27,000 for being bloody raped 20 times.” O’Brien read from the evidence to the committee of an unnamed victim. Pell called that miserly; he said he was willing to re-examine old settlements. But he defended absolutely the laws that make it essentially pointless to sue the Catholic church in Australia.

“My ambition,” he said, “is that we should be generous.” But he told the committee he sees no reason to follow that “very litigious society” the US where the average payout to victims of clerical child abuse is over a million dollars. The law is his great support here. He is not calling for it to be changed. “We are more than happy to pay according to the prevailing Australian norms,” he said.

The gallery was fractious but the long afternoon had gone with few interjections and only occasional bursts of laughter. The man with his finger ready on the kill button in case of outrages hadn’t had to cut the audio feed. No one was thrown out. An exhausted Pell was determined to end as he began on a note of apology. “I recommit myself to lamenting the suffering and doing what I can to improve the situation.”

George Pell - Everything Except His Testimony Spoke Of Power

- By John Richardson at 28 May 2013 - 7:20pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

4 min 9 sec ago

11 min 47 sec ago

10 hours 16 min ago

11 hours 50 sec ago

11 hours 20 min ago

11 hours 27 min ago

11 hours 38 min ago

13 hours 45 min ago

14 hours 24 min ago

16 hours 36 min ago