Search

Recent comments

- escalationing....

10 hours 1 min ago - not happy, john....

14 hours 20 min ago - corrupt....

19 hours 42 min ago - laughing....

21 hours 36 min ago - meanwhile....

23 hours 5 min ago - a long day....

1 day 59 min ago - pressure....

1 day 1 hour ago - peer pressure....

1 day 17 hours ago - strike back....

1 day 17 hours ago - israel paid....

1 day 18 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

dirty little secrets ....

The CSIRO has duped one of the world's biggest pharmaceutical companies into buying anti-counterfeit technology that could be easily compromised - passing off cheap chemicals it had bought from China as a ''trade secret'' formula.

Swiss-based multinational Novartis signed up two years ago to use a CSIRO invention it was told would protect its vials of injectable Voltaren from being copied, filled with a placebo and sold by global crime syndicates.

Drug counterfeiting is big international crime. An Interpol strike force last year in 100 countries led to the seizure of 3.75 million units of fake drugs, and the arrest of 80 people.

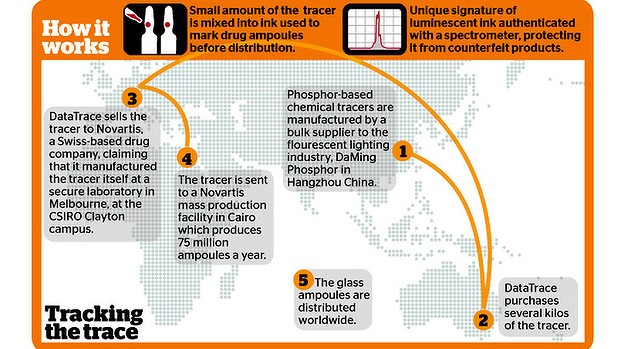

The invention sold to Novartis to protect against such counterfeit attacks - a microscopic chemical powder mixed into the ink that is painted on the neck of its Voltaren ampoules - was being marketed by DataTrace DNA Pty Ltd, a joint venture of CSIRO and DataDot Technology Ltd, a publicly listed company.

But a Fairfax investigation has established that senior CSIRO officials and DataDot executives deliberately misled Novartis about the technology in order to close the deal, after receiving explicit internal warnings that the Novartis code could be easily duplicated.

Now, hundreds of millions of Voltaren ampoules across the world could carry the easily compromised DataTrace product. The injectable version of the drug is not approved for use in Australia.

Three months before the deal was signed, the key ex-CSIRO scientist working on the technology, Dr Gerry Swiegers, warned against proceeding with the deal.

''The code which has been offered to Novartis may not be fit for purpose … because the code material is commercially available from a variety of vendors,'' he wrote to DataTrace in March 2010.

''If there is a serious counterfeiting threat to the Novartis ampoules, then this code risks being quickly and easily cracked in a counterfeiting attack. Serious questions could then be raised, especially if the successful counterfeiting attack resulted in injury or death.''

Dr Swiegers, who was retrenched from CSIRO after a bitter falling-out, has since been agitating for reform of the peak scientific body.

The deal went ahead in July 2010. And despite having promised to supply a unique tracer code specifically for Novartis, DataTrace instead issued the company a cheap tracer it had previously bought in bulk from a Chinese distributor.

The bulk tracer originally had been earmarked to sell to mining multinationals for low-risk applications such as sorting high from low-quality iron ore.

Such applications had no real security concerns, and this tracer formula was widely available at the time.

But when DataTrace sold the same agent to Novartis, it told the company the formula was a trade secret, and Novartis is believed to have been contractually forbidden from trying to identify its make-up - a standard industry practice.

Had Novartis reverse-engineered the tracer potentially in breach of its contract, it would have been able to identify its components and check whether the phosphor formula was available elsewhere. In fact, at least two firms were selling the identical material to hundreds of firms around the world.

Damning internal documents seen by Fairfax show DataTrace and some of the most senior officials at the CSIRO knew that Novartis was being misled in a deal believed to be worth $2.5 million.

On August 7, 2009, Greg Twemlow, the DataTrace general manager who engineered the deal with Novartis, emailed Peter Osvath, a CSIRO research group leader, and Geoff Houston, a CSIRO commercial manager, with this subject line: ''Proposed answer to the question, 'is our Tracer code commercially available'.''

''This is how we propose to answer the question if it's posed. We want everyone answering consistently. Answer: The CSIRO will make your Novartis codes using their Trade Secret methods and I'm sure you'll appreciate the importance of secrecy for Novartis and all of our clients. Having said that, there may well be a possibility that aspects of the code could be simulated with commercially available products.''

But it was much more than a possibility.

Counterfeiting was such a serious commercial and public health risk that Novartis went to extraordinary lengths to ensure DataTrace and CSIRO had security measures in place to prevent the code being cracked.

In August 2009, a team of auditors from Novartis visited CSIRO's Clayton campus.

A year later, proposed changes were made to the lab, the Novartis auditors were satisfied by CSIRO's security measures, and in July 2010 DataTrace inked a five-year deal.

Just three months after the deal was announced to the market, CSIRO sold its 50 per cent stake in the company, worth $1.3 million, in return for 8.93 per cent of DataDot Technology Ltd.

CSIRO Duped Global Drug Firm With Generic Chemicals As 'Secret Formula'

- By John Richardson at 11 Apr 2013 - 1:40pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

whoops ....

Confidential reviews of the CSIRO by some of the world's most accomplished scientists show that the once great institution is now unable to act in the best interests of advancing research.

They found the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation was being strangled by a bureaucratic labyrinth stifling innovation and persuading science leaders to abandon the 87-year-old institution, the reviews say.

One of Australia's most renowned scientists, who wished to remain anonymous, said the nation's peak research body had lost its way and should ''remove the S from its name''.

On Thursday night Science Minister Don Farrell demanded answers from the CSIRO after the Herald reported that officials and others involved in a spin-off joint venture knowingly passed off cheap Chinese chemicals as their trade-secret formula.

In a deal believed to be worth $2.5 million, the venture sold the technology to the Swiss drug company Novartis, one of the biggest pharmaceutical makers.

It was part of its high-security anti-counterfeit technology to protect hundreds of millions of injectable Voltaren ampoules distributed overseas. Voltaren is an anti-inflammatory.

Novartis has confirmed it has begun an investigation into the affair and the federal opposition has called for an independent inquiry into the entire organisation. A dozen previously unreleased assessments reveal the organisation had become bogged down in bureaucracy, doubling the number of managers and putting excessive emphasis on basic paid consulting work at the cost of time and resources for real science.

Its focus on short-term projects was ''paralysing the ability of the groups to act creatively and strategically in the best interests of advancing the science''.

Former CSIRO staff, including division chief Max Whitten, said it was no longer recognised as a world-leading scientific institution, an accusation it vigorously disputes, citing a separate review by a former chief scientist in 2006.

One previously unpublished review, of the earth science and resource engineering division, reported consistently negative responses from all research groups it interviewed about the management model.

''The panel considers that this is … seriously undermining the quality of the research,'' the review says. ''In our opinion, the costs significantly outweigh the putative advantages.'' The sentiments were echoed in many other reviews, including the nutrition group which found its ''once world-leading laboratories have lost that position, and with a number of exceptions, are now followers of the best front-line centres''.

The reviews commend some areas for world-class research but repeatedly criticise the management structure, which it has dubbed the ''matrix''.

This matrix was incrementally introduced from 2003 by former chief executive Geoff Garrett, aimed at conducting more science targeted to specific problems facing industry, government and the community. Dr Garrett dismantled many of the 22 divisions. In their place he introduced entities called ''flagships'', which are more focused on generating revenue.

Critics say that while the goals of many flagships were worthy, it was inappropriate for the research of the country's leading scientific organisation to be tied to financial benchmarks because it stifled scientific discovery.

Under the present structure, the 12 divisions host the organisation's scientific capacity - its staff, infrastructure and expertise. But these resources are mainly used to service projects run not by the divisions but the flagships.

In the past, the CSIRO's reputation for producing highly valuable and independent science was based on its divisions, led by internationally respected scientists. ''Now CSIRO doesn't enjoy a good reputation in many areas,'' said Dr Whitten.

The reviewers found the matrix fragmented researchers among multiple projects and answerable to several managers. Reviewers of the land and water division found the needs and priorities of the flagship dominated decisions about what science to undertake.

Despite the criticism of the inner workings, staff scientists have achieved successes in the past few years, including developing a hendra vaccine and securing Australia as a co-location for the world's biggest radio telescope. The review's complaints also contrasted sharply with a review of the flagship program conducted by the former Australian chief scientist Robin Batterham in 2006, which praised the matrix structure. The deputy chief executive, science strategy and people, Craig Roy, rejected suggestions the matrix had increased management, saying the organisation had reduced its 27 divisions and flagships in 2003 to 23 entities now.

''In 2002 the organisation wasn't structured to focus on the big issues of low emissions energy, water, oceans, health, food. Those are the places where, in many cases, we're leading the national R&D agenda today,'' he said.

The organisation was also addressing criticism its divisional research was fragmented and researchers were too stretched. ''In the last six months we've been working … to address … [the issue] of fragmentation [to] make life easier for scientists so they can focus more on their science,'' he said.

The general manager of science excellence and standing, Jack Steele, said only a ''sliver'' of the CSIRO's work was contract testing for industry. ''Almost all of our activity has a component of discovery associated with it.''

Call For Inquiry As CSIRO Comes Under The Microscope