Search

Recent comments

- conspiracy....

11 hours 35 min ago - brutal USA....

13 hours 30 min ago - men....

13 hours 51 min ago - oil....

14 hours 27 min ago - system....

15 hours 14 min ago - not invited....

15 hours 49 min ago - whistleblow.....

1 day 5 hours ago - demosocialism....

1 day 14 hours ago - front cover up....

1 day 14 hours ago - the trick....

2 days 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

game over .....

In one sense, Inequality for All is absolutely the film of the moment. We are living through tumultuous times. The economy has tanked. Austerity has cut a swath through the country. We're on the verge of a triple-dip recession. And, in another, parallel universe, a small cohort of alien beings – or as we know them, bankers – are currently engaged in trying to figure out what to spend their multimillion-pound bonuses on. Who wouldn't want to know what's going on? Or how it happened? Or why? Or if it is really true that the next generation down is well and truly shafted?

And yet… what sucker would try to make a film about it? It's not exactly Skyfall. Where would you even start? Because there are some films that practically beg to be made. And then there's Inequality for All; the kind of film that you can't quite believe that anybody, ever, considered a good idea, let alone had the passion and commitment to give it two years of their life.

How did you even come up with the idea of making a film about economics? I ask the director Jacob Kornbluth. "I know! People would roll their eyes when I told them.

They'd say it's a terrible idea for a film." On paper it is, indeed, a terrible idea. A 90-minute documentary on income inequality: or why the rich have got richer and the rest of us haven't (I say "us" because although it's focused on America, we're snapping at their heels) and which traces a line back to the 1970s, when things stopped getting better for the vast majority of ordinary working people and started getting worse.

"It always sounded so dry," says Kornbluth. "But then I'd tell people it's An Inconvenient Truth for the economy and they'd go, Ah!"

In fact, Inequality for All, which premiered at the Sundance film festival a fortnight ago, is anything but dry. It won not just rave reviews but also the special jury prize and a major cinema distribution deal, and while it owes an obvious debt to Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth, it is, in many ways, a much better, more human and surprising film. Not least because, incredibly enough, it's actually pretty funny. And, in large part, this is down to its star, Robert Reich.

Reich is not a star in any obvious sense of the word. He's a 66-year-old academic. And he's been banging on about inequality for more than three decades. At one point in the film he looks quite downcast and says: "Sometimes I just feel like my life has been a total failure." An archive clip of him on CNN from 1991 looking fresh-faced and bushy-haired shows that he has literally been saying the same thing for decades upon decades. And yet, as he tells me cheerfully on the phone from his home in California, "It just keeps getting worse!"

These days he's a professor of public policy at the University of California at Berkeley and while he's not a figure we're familiar with in the UK, he's been part of American public life for years. At the start of the film, he introduces himself to a lecture hall full of students, telling them how he was secretary of labour under Bill Clinton. "And before that I was at Harvard. And before that I was a member of the Carter administration. You don't remember the Carter administration, do you?" The students remain silent. "And before that," says Reich with impeccable comic timing, "I was a special agent for Abraham Lincoln." He shakes his head. "Those were tough times."

Reich's books and ideas have been at the forefront of Democratic party thinking for a generation. He is an intellectual heavyweight, a veteran policymaker, a seasoned political hand, and yet he also has the delivery of a standup comedian. His ideas were the basis for Bill Clinton's 1992 election campaign slogan, "Putting People First" (they were both Rhodes scholars and he met Clinton on board the boat to England; he once dated Hillary too, though he only realised this when a New York Times journalist rang him up and reminded him). And they were still there at the heart of President Obama's inaugural address last month. America could not succeed, said Obama, "when a shrinking few do very well and a growing many barely make it". What Reich, basically, has been saying since the year dot.

What's extraordinary is how, somehow, these ideas have been translated into a narrative that shows every sign of being this year's hit documentary film. It certainly shocked Reich. He says he was amazed when Kornbluth first pitched the idea of a film. "He came and said that he'd read my book, Aftershock, and that he loved it and wanted to do a movie about it. And I honestly didn't know what he meant. How could you make a movie out of it?"

But Kornbluth has made a movie out of it. A really astonishingly good movie that takes some big economic ideas and how these relate to the quality of everyday life as lived by most ordinary people. The love and care and artistic flair that Kornbluth brought to it is evident in every frame. It was really really hard work, he tells me, to make something look that simple. But then "I grew up poor. So I've always been very aware of who has what in society." His father had a stroke when Kornbluth was five and died six years later. And his mother, who didn't work because she was raising three children, died when he was 18.

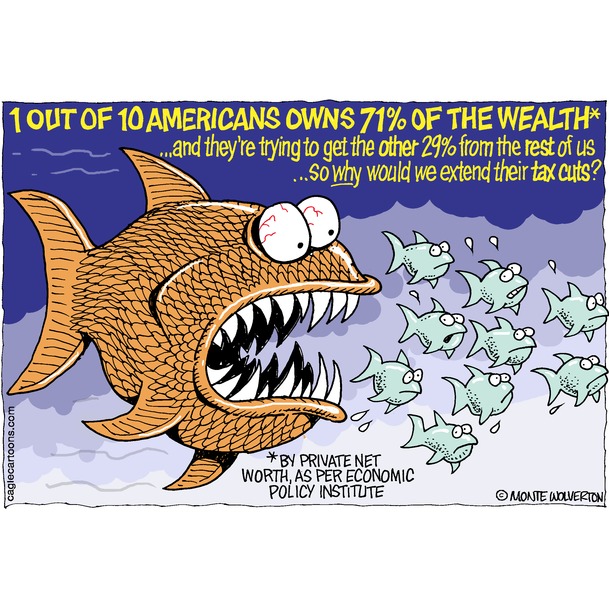

Any synopsis of the film runs the risk of making it seem dry again, but essentially it describes how the middle classes have come to have a smaller and smaller portion of the economic pie. And how, since 70% of the economy is based on the middle classes buying stuff, if they don't have any money to buy this stuff, it cannot grow. Meanwhile, the government has allowed the super-rich, the "one per cent", to take more of the nation's wealth. Half of the US's total assets are now owned by just 400 people – 400! – and, Reich contests that this is not just a threat to the economy, but also to democracy.

meanwhile ….

Antony Jenkins, chief executive of Barclays, who appears before MPs and peers on the banking standards commission this week, has removed one issue from the agenda, namely his right to a bonus of more £1m. The bank has been fined £290m for rigging the benchmark Libor rate, has set aside £2bn to pay claims for mis-selling payment protection insurance and faces an official investigation by the Serious Fraud Office and the Financial Services Authority into its dealings with Qatar at the height of the 2008 financial crisis. So this is the least Jenkins could do. The announcement of his monetary self-denial on Friday signals a belated sensitivity on the part of those who have benefited most from one of the least attractive sides of capitalism.

Jenkins acknowledges that Barclays has "…multiple issues of our own making". And, he added: "I think it only right that I bear an appropriate degree of accountability and I have concluded that it would be wrong for me to receive a bonus for 2012 given those circumstances." His references to "right", "wrong and "accountability" are presumably what David Cameron was seeking when he said four years ago: "We must shape capitalism to suit the needs of society; not shape society to suit the needs of capitalism." Then in opposition, he advocated "capitalism with a conscience". More recently, Ed Miliband has – so far hazily – tried to define "responsible capitalism".

What's missing is how both concepts translate into practical governance, for instance in regulation, taxation and the allocation of sparse resources. As a result, many bankers, among the notorious "1%" of the richest and most powerful, continue to rule very much OK – for now. But an awareness is growing across the political spectrum, and on both sides of the Atlantic, that a radical recalibration of capitalism is essential, not least because the wealthiest and least productive are in danger of allowing their own avarice to sabotage the very system on which they have become so hideously bloated.

Last month, Barack Obama, on his re-election to a country with 42 million living in poverty, warned: "America cannot succeed when a shrinking few do very well and a growing many barely make it." At the World Economic Forum in Davos, its founder, Klaus Schwab, said: "Capitalism in its current form no longer fits the world around us." How badly it "fits" is powerfully demonstrated in Inequality for All, a documentary made by Jacob Kornbluth, that recently won the special jury prize at the Sundance festival. As discussed in today's New Review, the film "stars" Robert Reich, professor of public policy at Harvard, prolific author, campaigner, former labour secretary under Bill Clinton, a charismatic man whose lectures are renowned for the way he surgically dismembers the mutant capitalism that has taken hold in the US over the past 40 years.

While the debate in the UK is mostly focused on growth and how best to engender it, Reich explains in chilling detail why growth alone may not be enough. For too many, he explains, social mobility has begun to slide backwards. A small but growing band of global pirates – billionaires all, without allegiance to community or country, devoid of civic responsibility – accrue wealth from the continued immiseration of the squeezed majority. These hugely rich are fawned over and subsidised by governments even as inequality widens to a chasm that may yet produce social unrest.

Reich's analysis is similar to that of the UK thinktank, the Resolution Foundation. It launches its definitive study of low- to middle-income families, Squeezed Britain, this week. Britain has more than 10 million adults living on between £12,000 and £30,000 gross, the majority in work. However, this squeezed middle is fast becoming the squeezed majority, with even those on £50,000 seeing their children's prospects decline. The cause, Reich points out, is that while wages have flattened for years, the cost of living has spiralled and the richest have accelerated away. In the US, in 2008, 400 billionaires were "worth" more than 150 million of the US population. British housing statistics published last week indicated a similar contemptible polarisation under way here. The 10 most expensive boroughs in London, packed with Russian oligarchs, have a combined property "value" of £552bn, identical to that of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland combined.

Over the past few decades, average families have coped by more women going into employment, by working longer hours and by credit. But since 70% of the US economy is based on consumer spending, a lack of surplus cash means the engine is running out of fuel. The rich are small in number and don't spend nearly as much as the majority. "Free" markets with the rules written by the richest result in a shrinking public sector, deregulation, unemployment, low taxes for the most affluent and the threat of globalisation, depressing wages still further. The sum impact isn't "bad" capitalism, it is modern-day capitalism. How it changes, and how rapidly, is a challenge to its own survival. Once, the advancement of the employee was a part of the social contract. Under Thatcher, the aspiration of the average citizen was central via shareholding and home ownership. Now, a more brutal set of priorities pushes the requirements of "the little man" aside, while those who have money buy the influence that unjustly shapes the world in which we live. So how do we forge again the link between morality and the markets?

Iceland, post 2008, forced the resignation of the government, refused to bail out the banks and placed 200 "banksters' under investigation. In 2011, its economy grew by 2.9%. Would a similarly tough approach persuade some of today's pirates that the much mocked habits of the bourgeoisie do have a value that also matters: moderation; giving something back; a sense of civic duty. In that context, Apple would desist from legitimately funnelling more than a billion dollars' worth of iTunes sales through the tax haven of Luxembourg, while the British Virgin Islands would no longer be home to 30,000 people but a staggering 457,000 companies legally siphoning money that could build sustainable communities.

Reich's agenda for positive change includes more jobs; greater investment in skills and higher education; a just taxation regime; strong unions; investment in public infrastructure; a living wage and a narrowing of the earnings gap. Reich ends with a warning: "We are losing the moral foundation stones on which our democracy is built," he says. How much more evidence do we need?

The Growing Wealth Gap Is Unsustainable

and …

The growing disparity between house prices in London and the South-east and those in the rest of the United Kingdom was revealed today, prompting fresh concern among first-time buyers and fears for the national economic recovery.

Research shows that the net value of properties in just 10 London boroughs – Westminster, Kensington & Chelsea, Wandsworth, Barnet, Camden, Richmond, Ealing, Bromley, Hammersmith & Fulham and Lambeth – now outstrips the worth of all the properties in Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland combined.

Elmbridge, a leafy corner of the Surrey stockbroker belt bordered by the Thames and the M25, which is home to just 131,000 people, is now worth £31bn – more than Scotland’s biggest city, Glasgow, where a population of 1.75m inhabits homes valued at £29bn. Property in the Royal Boroughs of Windsor and Maidenhead outstrips that in the whole of Cardiff.

But it is in London that the extraordinary gulf is most starkly illustrated, according to the research by the property group Savills as part of its latest Valuing Britain analysis of the UK market.

The capital’s richest borough, Westminster, with 121,600 dwellings, is worth £95bn – more than twice the value of Edinburgh (pop 500,000) and three times that of England’s sixth most populous city, Bristol.

Lucian Cook, the director of Savills residential research, said the findings showed that wealth was becoming increasingly concentrated in fewer hands, with future generations in danger of being priced out of buying in the London area and trapped for life in the rental sector.

“It is difficult even for owner-occupiers to trade between regions unless they are in other high-value areas of the UK. This might not be such a problem for people in Bath but it might be for those in Swindon,” he said. “Similarly not for those in York or Harrogate although it could be for those living in Leeds.

“If we have a market that is really constrained in terms of mortgage finance it will be very hard for areas to catch up and we expect the difference to widen in the next five years.”

The total value of the UK property market has risen by nearly two thirds in the past decade to £5 trillion although this is still 6.4 per cent off the 2007 peak.

By contrast, homes in London are worth £1.12trn, accounting for nearly a quarter of the entire value despite making up just 12 per cent of the total stock. Residential real estate in the capital is now worth 14.2 per cent more than it was at the pre-credit crunch height.

The most sought-after areas in London, such as Mayfair and Knightsbridge, continue to benefit from the influx of money from the Middle East, Asia and Eastern Europe.

However, other parts of the capital have benefited from the sheer levels of equity in the housing market, which has seen increasing amounts of cash chasing the same number of desirable properties, resulting in rising prices.

Alexandra Jones, the chief executive of the independent think tank the Centre for Cities, said future economic growth would benefit from reducing the wealth gap between London and the rest of the UK.

“Some of the cities such as Manchester, Leeds and Glasgow have improved over the past 15-20 years and have done really well,” she said. “But London has boomed and was the last in and the first out of the recession.

“There is a big worry that people can’t afford houses in places where there are jobs. That is a big problem not just locally but for the national economy. It is important to tailor policies for each individual area.”

10 London Boroughs Worth More Than All The Homes In Wales, Scotland & Northern Ireland

- By John Richardson at 4 Feb 2013 - 3:48pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

printing money ....

Barclays' controversial tax avoidance division generated revenue of more than a £1bn a year between 2007 and 2010, according to data published in a scathing review of the embattled bank's culture.

The assessment by City lawyer Anthony Salz, commissioned by Barclays in the wake of the Libor-rigging scandal, produced data for the first time showing that in the 11 years to 2011 the structured capital markets arm generated revenue of more than £9.5bn. Profit numbers were not published but Lord Lawson, the former Conservative chancellor who sits on the parliamentary commission on banking standards, has accused the secretive division of "industrial scale tax avoidance".

The new chief executive of Barclays, Antony Jenkins, has insisted the division is being shut down as he attempts to clean up the image of the bank. But Salz found that the 100 highly-paid bankers in SCM have been redeployed around the organisation, instead of being fired.

In 2009 the Guardian revealed how SCM structured complicated deals to root money to offshore centres to avoid tax.

The Salz review also sheds light on the amount of tax paid by Barclays in 2012. Just £82m in corporation tax was paid to the exchequer after top line profits of £7bn shrank to £246m, as a result of an accounting standard relating to how it values its own debt.

Barclays has also faced fierce criticism for its admission that it paid just £113m in corporation tax in 2009.

Salz, who describes Barclays bankers as losing a "sense of proportion and humility", also described a pay structure in the retail bank which may have encouraged the mis-selling of payment protection insurance. He reveals that the bank had a market-leading share of PPI sales in 2005 and was bringing in revenues of £400m a year from the discredited insurance. High street banks have now taken provisions of more than £12bn in mis-selling claims related to PPI products.

Barclays Tax Avoidance Division Generated £1bn A Year – Salz Review

meanwhile …..

Australia will force corporate giants such as Google and Apple to disclose their tax arrangements in an effort to curb alleged tax avoidance by multinational corporations.

The increasingly borderless global economy means big firms often have no tax liability in a country, even with a major local presence, assistant treasurer David Bradbury said on Wednesday.

In Australia, multinationals including the local arm of Google have been accused of shifting income to countries such as Holland or Ireland where tax rates are lower.

"This should not be a guessing game," said Bradbury after releasing measures that would require about 2,000 large and multinational businesses, including miners BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto with yearly revenue of A$100m (£69m) or more, to have their tax details published by the government.

"The government intends to improve transparency around how much tax large enterprises are paying. We want to make sure that large multinational companies are paying their fair share," he said.

Australia's minority Labor government last year released draft revisions to tax laws to stop profit-shifting in line with a push by Britain and Germany, and discussions last year within the Group of 20 wealthy nations.

Asked in a radio interview on Wednesday about alleged profit-shifting by Google, the prime minister, Julia Gillard, said she did not want to single out any company but said profit-shifting was an international issue requiring action by G20 nations.

"As a matter of principle, taxpayers, whether they're companies or individuals, should pay their proper rate of tax," Gillard said. "This is an ongoing discussion at an international level."

The revisions, opposed by opposition conservatives, will be voted on by parliament after the 14 May budget, with the government requiring support from a handful of independent lawmakers and Greens holding the balance of power.

The amendments aim to shut down loopholes that risk the loss of more than A$1bn in government revenues each year by allowing IT firms to avoid or reduce tax through online sales.

Australia's corporate tax rate is 30%, compared with 12.5% in Ireland. Major companies including Rio Tinto have already begun publishing tax details, expanding on information in existing financial statements.

Australia To Force Multinationals To Disclose Tax Arrangements