Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

walking away from omelas ....

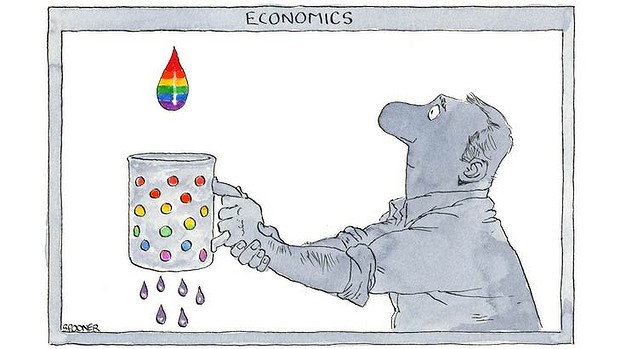

Our nation might be rich but rampant consumerism is not making us any happier

I have been reading the excellent How Much is Enough? by the economist son and philosopher father Robert and Edward Skidelsky. They argue that developed nations, such as ours, are on a blind pursuit of consumption. They point out that we are unable to stop this consuming, despite it killing us, killing wealth distribution and probably killing the environment. They conclude that despite increasing our wealth, we're no more happy - possibly unhappier - and that we are working to ''an ethic of acquisitiveness, which dooms societies to continuous objectless wealth creation''.

They bluntly outline that our way of life feeds our insatiability and insatiability feeds our way of life. As Eva Cox recently asked, ''I'm not sure if I am working to live, or living to work?''

And hell-bent on wealth creation are we. According to Credit Suisse we are now rated as the second wealthiest country. Despite our own local economic pessimism, outside our shores we are considered an economic phenomenon. Our debt rate is among the world's lowest, our employment rates among the world's highest and our outlook is not as gloomy as many would like us to believe. As Ian Harper puts it, we are in ''rude health'' when it comes to our economy. However, paradoxically, we also punch above our weight with regard to our poverty profile.

Indigenous living and health conditions continue to be pitiful in many parts of Australia and, in many sad aspects, world-beating - take for instance indigenous children's hearing loss ranking as the worst in the world of any given population. Two million Australians now reside in poverty conditions (including 12 per cent of the country's children), and our overall poverty rates have risen an astonishing 50 per cent over the past 12 years.

It is little wonder that in marking the 10th anniversary of Anti-Poverty Week, a group of eminent former patrons, including Janet Holmes a Court, Fiona Stanley and Tim Costello, have called for a national development goal to progressively reduce poverty in this country.

They argue that we need an agreed measure of poverty, such as the Australian National Development Index, to annually measure, and motivate our progress towards reducing disadvantage; one that sits outside the normal economic indices.

What does this mean in terms of how we view poverty in Australia? Poverty is obviously about the lack of wealth or income to meet basic goods. In our terms, 11 per cent of the population lives below the poverty line, and even larger numbers reside in unaffordable or unstable housing.

Poverty is also about wealth distribution, and a consumer society such as ours means we have wide wealth disparities. Australia now ranks as one of the most unequal in wealth distribution, with deep-seated intergenerational poverty now emerging in many parts of the country. For example, just 1.5 per cent of Victorian postcodes account for 20 per cent of the top indicators for disadvantage.

Rates of depression, obesity, marriage breakdown, and chronic drug and alcohol abuse - these are all casualties of our wealth pursuit, and we feature high against world standards. Further, living in a society that is promoting conspicuous consumption, even by those who cannot afford it, can trigger other poverty conditions such as mortgage breakdowns, bankruptcies and credit card debt.

Against such trends it is little wonder the often underrated condition of loneliness is featuring more, with 20 per cent of Australians older than 18 now considering themselves socially disconnected, and one-third of Victorian communities experiencing low social cohesion. It seems, despite our wealth, we are more unattached, certainly more unequal, and ultimately more unlikely to involve ourselves in wider community life than ever before.

The irony is that while Australia is a most desired economy, the habitual pursuit of wealth has left us not only incapable of enjoying it properly, but sharing it accordingly and, more important, becoming more motivated to fix the resulting poverty issues it conjures up. Instead, treasurers around the country are captured by ''acquisitiveness''. They insist on the pursuit of surpluses at any cost, without considering that a nation, in good economic health, could be justified to spend bravely on such nation-defining issues as indigenous health, education achievement in our poorest neighbourhoods or the chronic shortage of affordable housing.

However, solutions to these problems are not easy for us to accept. For instance, the current housing crisis could be fixed through tax treatment, rather than more money. But are we really prepared to give up our tax advantage for the betterment of the wider group? Now that's a test for government.

Ursula Le Guin once wrote a remarkable short story on an imaginary society called Omelas. This was a place where everything is bountiful, everyone enjoyed wealth and life's goods were in abundance. However, for this utopia to continue, it required the suffering of one child locked in a cage deep in the bowels of the township. The story challenges our thinking - can we enjoy fully our fruits when even one life suffers?

Australian life is not Omelas, nor could it be viewed in such stark terms, but there is certainly enough dramatic inequality in our nation, where chronic poverty sits side by side with lucky wealth.

Such circumstance calls us to get a better grip of ourselves and our surroundings. If our pursuit of wealth is unlikely to temper, then we should also devote such wealth to resolving the tough but solvable poverty problems on our landscape. Only then would our good story of a wealthy and fundamentally lucky nation be more complete.

Paul McDonald is Victorian co-chairman of Anti-Poverty Week and CEO of Anglicare Victoria.

- By John Richardson at 17 Oct 2012 - 8:21am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

4 hours 15 min ago

5 hours 31 min ago

6 hours 12 min ago

7 hours 9 min ago

16 hours 10 min ago

16 hours 24 min ago

21 hours 4 min ago

22 hours 28 min ago

22 hours 37 min ago

23 hours 37 min ago