Search

Recent comments

- crummy....

2 hours 10 min ago - RC into A....

4 hours 3 min ago - destabilising....

5 hours 7 min ago - lowe blow....

5 hours 39 min ago - names....

6 hours 16 min ago - sad sy....

6 hours 41 min ago - terrible pollies....

6 hours 51 min ago - illegal....

8 hours 3 min ago - sinister....

10 hours 25 min ago - war council.....

20 hours 10 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

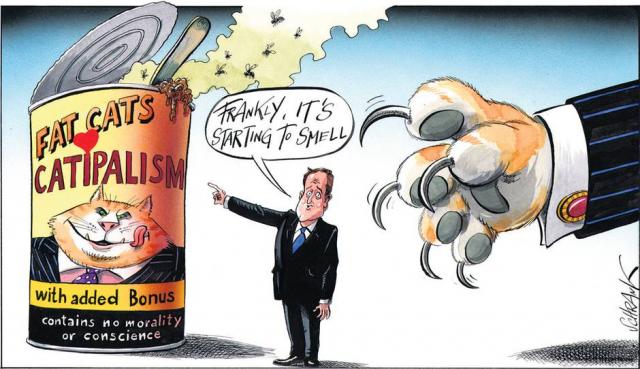

on the nose .....

The government faces renewed pressure to announce tough measures on bankers' pay this week as data shows that the average remuneration for 1,265 senior staff was £1.8m in 2010.

The analysis of regulatory disclosures by eight leading banks comes as the business secretary, Vince Cable, prepares to announce on Tuesday how he will tackle the issue of executive pay.

Research by the Guardian has found that the average pay deal was £1m or more for employees regarded as having the most influence over risk-taking activities at their firms. The highest average was at Goldman Sachs (£4m) and the lowest at HSBC (£1m), during a year when data from the Office for National Statistics showed the average wage in the UK was £25,900.

Banks are being forced to publish the information for the first time under European rules that are helping to lift the lid on secretive City bonuses at a time when top pay is a politically charged issue.

Executive pay has been rising faster than salaries for the average worker across the UK and Cable is expected to announce a range of measures to give shareholders more powers to vote down pay deals. However, he is expected to step back from putting employees on remuneration committees.

In 2010, the pay of the bosses of the UK's top 100 companies jumped by an average of £1.3m to almost £4.5m, according to the High Pay Commission, which has been influential in setting the policy changes that Cable intends to announce.

The government's policies on pay are being announced as bonuses for 2011 are handed out across the City and the bonus arrangements for the bailed-out Lloyds Banking Group and Royal Bank of Scotland are being discussed.

The remuneration committee at RBS is expected to meet this week amid pressure from David Cameron to ensure the bonus for the chief executive, Stephen Hester, is lower than last year's £2m. A figure of £1.5m has been mooted.

The deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, said he expected the RBS bonus pool to be "considerably lower" than it was last year. "We have been very, very clear that in RBS - and for that matter in other banks - the bonus pool has got to be considerably lower than it was last year," he told BBC1's The Andrew Marr Show.

Asked about Hester's rumoured payout, he added: "You are asking me about a hypothetical outcome that I don't believe will arise."

Ed Miliband went further on Sunday night, calling for Hester to be stripped of his bonus altogether. "If responsibility means anything I don't think he should be getting his bonus," he told BBC Radio 5 Live's Pienaar's Politics.

Lord Oakeshott, the Liberal Democrat peer who resigned as a Treasury spokesman over the lax treatment of banks by the coalition, said: "This lifts the lid for the first time on the heaving cauldron of gambling and greed in London's investment banks - 1,265 investment bankers collected £1.8m, on average in a single year, almost 75 times the average wage."

The regulatory filings of eight leading banking groups - Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Citi, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Nomura, Barclays, Royal Bank of Scotland and HSBC - were analysed for the information provided about "code staff". These are the individuals deemed to be responsible for managing and taking risks. The data is for the year to 31 December 2010, except for Nomura, which is for the year to 31 March 2011.

For non-UK banks, the filings are for the UK or European operations. The highest average deal was at Goldman Sachs Group Holdings (UK) which had 95 code staff in 2010 who were received an average of £4m through schemes whose ultimate value will be known in five years and depend on the share price.

In addition, bonuses in shares - yet to vest - worth about £390m were handed out at Goldman Sachs in 2010.

JP Morgan has 82 code staff who were paid an average of £2.6m in 2010, Citigroup 95 who fall within the definition and were paid an average of £2m, while at Nomura, which expanded in the City after buying some of the operations of the collapsed Lehman Brothers, the average was £2.1m for 65 code staff. At Merrill Lynch UK Holdings, owned by Bank of America, the 94 code staff earned an average £2.3m. Eight individuals received £22m in signing-on fees during 2010. Data from the UK banks was first published last year.

At Barclays there were 231 code staff with an average of £2.4m while HSBC had 280 on an average £1m. At RBS there were 323 code staff with an average of £1.1m. These banks have more code staff as they are based in the UK, where their operations are larger than those of the international players. The numbers for UK banks also include overseas staff.

Jon Terry, a partner at consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers, said this was the first time such levels of pay had been disclosed by banks and would contain some discrepancies. "Within code staff there will be a head of compliance and a head of equities, who is going to earning relatively more," said Terry.

Eight City Banks In £1.8m Pay Spree

meanwhile ....

The image of Sir Fred Goodwin sporting tweed shooting jacket and "broken" double-barrelled shotgun has come to symbolise all that is wrong with crony capitalism and immoral bankers. "Fred the Shred" has become the target, an easy scapegoat, as if stripping him of his knighthood, as the Daily Mail demands, will atone for all the sins of the banking crisis; the 21st-century equivalent of mounting a criminal's head on a spike outside the Tower of London.

David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband all eagerly joined in last week to call for Sir Fred to lose his knighthood - even though this is subject to an independent committee of senior civil servants.

The party leaders have used Sir Fred to push their own case - be it "moral markets", "popular capitalism vs crony capitalism", "producers vs predators", or a "John Lewis economy".

But in the different versions of this same argument - all fine words promising a brighter future for society - will any of it make a difference to the current state of play? Or will it continue to be the case that the richest in society are left untouched by the Government's austerity agenda, while the poorest continue to suffer?

The politics in this are important. With the public so recently reminded of Sir Fred, chief bogeyman of banking, the Government, in particular, is under pressure to offer more than tough words and vague action.

Enter Vince Cable, the Business Secretary, who will this week unveil plans to clamp down on executive pay, empower shareholders and give employees a greater say.

Although some of the moves have been already trailed by the Prime Minister and Mr Clegg, Mr Cable is planning a "tough" crackdown on boardroom pay which he believes will address concerns in his party that the Lib Dems are not pushing the fairness agenda inside the coalition.

Mr Cable, who was still drafting his speech last night, is finessing plans to tax banks and other firms who fail to show restraint in awarding pay and bonuses - but faces resistance from the Treasury under George Osborne.

Central to the coalition battle over executive pay is the role employees can play. Mr Cable is adamant that the huge rise in executive pay in the City is at odds with the success firms achieve. He wants to see employees on remuneration panels, arguing they can bring "a helpful, fresh perspective". The battle will go to the wire. "Vince is very keen, the PM and Chancellor aren't," said a government source.

The average total remuneration of chief executives in FTSE 100 companies was £1m in 1998, but topped £4.2m in 2010. While salaries have remained relatively static, the levels of bonuses, long-term incentive plans and pensions have grown dramatically.

Mr Cable will call time on "payouts for failure", forcing firms to have a set policy on golden goodbyes to prevent failing bosses walking away with millions. Shareholders will be given clearer information on the proportion of company profits paid to executives, compared with dividends and employee pay.

He is expected to halt the City merry-go-round which has seen directors from different firms serving on each others' remuneration boards, which has helped drive up pay across companies. Shareholders will be given a binding vote on executive pay. Mr Cable is also keen to reverse the trend that has seen pay at the top rise sharply, while "shop-floor" staff have received meagre increases, or even pay freezes.

Part of bringing "morality" into markets is ensuring firms look more like the rest of society, including having more women both in the boardroom and on remuneration panels.

Lord Oakeshott, a former Lib Dem Treasury spokesman and an ally of Mr Cable, said: "The bosses of Britain's big companies are a self-selecting old boys' club: 310 of the FTSE 350 have not a single woman executive director, and progress is invisible to the naked eye."

Chuka Umunna, the shadow Business Secretary, will argue that Mr Cable's plans fall short of implementing the recommendations of the High Pay Commission, published last November, which called for greater transparency and accountability.

But will any of this be enough? The bonus season is already in full swing, and as he led the Government's assault on "crony capitalism" last week, Mr Cameron claimed that he would act to stop bosses of state-owned banks, such as the RBS boss, Stephen Hester, receiving excessive bonuses.

Mr Hester is in line for a £1.5m payout, even though RBS's share price halved over the past year, after he got a £2m windfall the previous year.

Angela Knight, chief executive at the British Bankers' Association, said the banking industry was the "inevitable target" of remuneration reforms, and called on the Government to cool criticism of the sector, making it clear that her colleagues would fight any reforms.

There is now an unstoppable backlash against Sir Fred, led by the Daily Mail and Facebook pages. Manifest, the shareholder proxy voting service, has scanned FTSE 100 boardrooms and identified 63 knights, 19 lords, seven baronesses and three dames. Yet why should the Honours Forfeiture Committee remove Sir Fred's knighthood when Lord Archer, for example, kept his peerage despite being jailed for perjury and perverting the course of justice?

But anyone could be forgiven for thinking that, as the leaders of all three parties went to war on greedy bankers last week, fairness was being restored in the system.

Yet at the same time, figures released by the welfare minister, Chris Grayling, and the immigration minister, Damian Green, claiming that there are "370,000 migrants on the dole" showed that there are those among the poorest in society who are being made scapegoats.

These figures, which were challenged by economists, were released against a backdrop of the Government's legislation on welfare reform, reducing benefits for the disabled and unemployed: the poorest. The Government will be judged not just by its fine words, but its deeds. And they know it.

So, why is no one calling for these bankers to lose their gongs?

•1. Sir Victor Blank

Knighted 1999. Chairman of Lloyds during the HBOS merger, just before it was bailed out. Faces US legal action

•2. Lord Stevenson of Coddenham

Ennobled 1999. Resigned as HBOS chairman after the Lloyds merger. Has apologised for bank's near-collapse

•3. Sir James Crosby

Knighted 2006. Resigned from FSA in 2009 after allegations he ignored a whistleblower while head of HBOS

•4. Sir Tom McKillop

Knighted 2002. RBS chairman in Goodwin's reign. Later admitted he had no banking qualifications

•5. Sir Philip Hampton

Knighted 2007. Chairman of RBS since 2009. Presided over rows about chief exec Stephen Hester's bonuses

•6. Sir George Mathewson

Knighted 1999. RBS group chief exec 1992-2001, chairman to 2006, then a £75,000-a-year consultant to the bank

•7. Sir John Bond

Knighted 1999. HSBC Holdings chairman until 2006. Vodafone row over £1.25bn tax bill blotted his copybook

•8. Helen Weird, CBE

Honoured 2008. Lloyds TSB finance director was awarded £875,000 bonus while retail executive director

•9. Philip Williamson, CBE

Honoured 2008. Ex-Nationwide chief exec got £1.6m on retiring, plus £605,000 salary and £374,000 bonus

•10. Lindsay Tomlinson, OBE

Honoured 2005. The ex-Barclays executive sold £5.5m-worth of bonus-scheme shares leaving him with £25m

- By John Richardson at 23 Jan 2012 - 9:15am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

grand larceny .....

Rich Ricci, Jerry del Missier and Bob Diamond took home paychecks of $15 million or more from Barclays bank last year, continuing a tradition of excessive pay in the UK. Bob Diamond, the CEO, made just shy of $28 million (£17.7 million), while Jerry del Missier and Rich Ricci, co-heads of Barclays Capital, made $17 million (£10.8 million) and $15 million (£9.7 million), respectively.

Of course this pales compared to what U.S. hedge fund managers make - Raymond Dalio of Bridgewater Associates was paid an estimated $3 billion in 2011, Carl Icahn of Icahn Capital Management earned $2 billion. The top European hedge fund manager in 2011 was Alan Howard of Brevan Howard Asset Management, who earned $400 million last year. All told, the 40 highest paid hedge fund managers were paid a combined $13.2 billion in 2011, according to a Forbes magazine survey.

Such pay-outs make Goldman Sach’s vice president Greg Smith’s estimated salary of $500,000 look like pocket change.

The UK salaries have become public knowledge because of a pact made by the banking sector with the UK government, as part of Project Merlin signed in February 2011. The plan – named after the fictional wizard – was intended to boost bank lending for small businesses. The project has been a failure so far with lending falling every quarter instead.

Yet Project Merlin has been successful in revealing how well bankers are paid, often despite doing very badly for investors, he most scandalous revelation so far comes from the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), which received $70 billion (£45 billion) of taxpayer funds. Despite the fact that the loss-making bank is now effectively 83 percent state owned, RBS handed out shares worth almost $44 million (£28 million) to nine of its top executives in 2010. All told it paid out nearly $1.5 billion (nearly £1 billion) to its senior employees – even as it reported losses of $1.7 million (£1.1 billion) for 2010 and slashed pension payments to its employees.

Shareholders protested at the RBS annual meeting last April. "You should not be paying yourselves anything until the debt is paid off to the government and to the people," said one attendee, characterising the pay scales as "really obscene to the degree of greed and corporate theft."

And it's not just the average citizen who thinks salary levels are excessive. Three out of four financial workers in the City of London who responded to a survey by St Paul's Institute thought the wealth divide was too big.

In 2010, five of Barclays top managers also shared a payout of £110 million. That year, the bank's top two earners were also Jerry del Missier and Rich Ricci , who made over $15 million each last year. It needs to be noted that Ricci, del Missier and Diamond are not the highest paid people at Barclays. That distinction goes to company traders, whose salaries do not have to be revealed under UK rules (as opposed to bankers).

Perhaps one of the most curious facts to emerge from the banker’s pay scandals in the UK are the fact that some of the bankers are employed and paid outside the banks themselves. For example Stuart Gulliver, HSBC's highest paid banker, is not employed by the bank's main holding company despite taking over as chief executive but by a Dutch-based company called HSBC Asia Holdings. Part of his salary is paid into a Jersey-based defined contribution scheme called Trailblazer. And Bob Diamond, chief executive of Barclays, is seconded to the bank from a Delaware subsidiary known as Gracechurch.

The banks say that there is no tax benefit to the arrangement.

Barclays Bankers Bonanza

crying poor .....

Executive pay is a hot topic, but one of ANZ's most senior executives says he is mystified that Australians love hearing about the millions paid to athletes and movie stars, but slam the remuneration of corporate leaders.

''We seem happy and even proud when our sports people make it onto the list of the top 20 paid people, or similarly when our entertainers make it on Hollywood's best-paid list,'' ANZ Australia chief executive Phil Chronican told an American Chamber of Commerce in Australia lunch yesterday.

''Yet for some reason when people are managing large complex businesses it is seen as excessive.''

Mr Chronican said the issue was not whether an executive was paid $1 million, $3 million, $5 million or more, but why.

''Just like sports people and entertainers, senior executives' careers do come to an abrupt end,'' he said.

Mr Chronican said the disclosure of the salaries of executives of listed companies was important for transparency.

''Maybe we should look to extend the disclosure to other groups who are in positions of power in their community, including those who are managing public superannuation savings.''

While acknowledging that for most Australians, "any level of executive pay looks high, even stratospheric", Mr Chronican, who earned a combined $2.2 million in compensation in 2011, said that the real issue was how big were the risks that bankers were hired to manage. "What returns do they earn shareholders? How do they serve customers? Are they good employers?"

In a wide-ranging speech, Mr Chronican, who oversees ANZ's domestic operations, said many Australians were not feeling the benefit of the mining boom, which had contributed to the change in consumer activity in recent years.

"Despite our strong economy, many Australians feel worried about our prospects in the face of uncertainty in Europe and many, particularly outside the fast lane of the mining and resource sector, feel they're not seeing the benefits," he said.

Although Australia continued to grow thanks to Asian demand for resources, the country was undergoing "a period of quite painful structural change", he said. Bank growth would be hit by slowing business and household credit demand, which remained at a 30-year low, while household savings were at a 30-year high.

The rising cost of banking would reduce shareholder returns from banks in the future, he said.

"Banking is going to be more expensive due to the higher costs of funds and higher regulatory requirements," he said.

Mr Chronican also noted an anomaly in overseas views of Australia and its real estate market.

"Overseas investors have a very odd set of views about Australian property prices," he said.

"They on one hand look at the stability and take a lot of comfort from it. The other is they cannot believe Australia was able to not have a property price collapse," Mr Chronican said.

ANZ Chief Mystified Over Anger At Executives' High Pay

doing the rooted cause analysis .....

Poor Phil Chronican just doesn’t get it.

What Phil & his ilk don’t understand is that a good many people are just as disgusted that a 16 year-old tennis player or the world’s dumbest ‘air-head’ celebrities can pull-down multi-million dollar payments, as they are at the exorbitant ‘rewards’ often received by our corporate high-flyers.

When I started my career some 40 odd years ago, the ‘rule of thumb’ that applied to executive rewards was that the CEO/Managing Director of an enterprise was never paid more than 12 times the level of pay received by the lowest-paid person in the enterprise. Where has that ratio gone?

Moreover, whilst the remuneration paid to some executives is clearly obscene, shareholder & community anger & resentment more often than not arises in situations or circumstances where the recipient has clearly failed to achieve their objectives whilst, more often than not, they have also destroyed significant shareholder value & many people’s lives in the process.

But I don’t blame Phil. The problem of excessive or unjustified remuneration exists only because of complacent shareholders who will not control their company boards or, in the case of some companies, largely controlled by institutions, the fact that there is an exclusive conclave of directors who network to serve their own interests ahead of those of the organisation.

still at the trough .....

Barclays is scrambling to head off a damaging revolt over the £17m pay package awarded to its chief executive Bob Diamond by changing the terms of his bonus for last year - just days before a crucial shareholder vote.

In an unscheduled announcement to the stock market that demonstrated its level of anxiety about a potential shareholder rebellion at next Friday's annual meeting, the bank also pledged to bolster dividends to try to address investors' concerns that it paid £2.1bn in bonuses last year - more than three times the £700m used to pay shareholders' dividends.

The surprise move came after the bank embarked on urgent canvassing of major investors earlier this week, asking them what could be done to limit the dissent prompted by Diamond's £2.7m bonus. There has also been investor anger over the decision to pay a £5.7m tax bill Diamond incurred when moving back to the UK from the US to become chief executive, after more than a decade running the investment bank Barclays Capital.

The bank will now more closely link Diamond's bonus to return on equity, which is the bank's net income after tax divided by shareholder equity. Diamond's return-on-equity target is 13% - well above the 6.6% achieved for 2011, a figure he described as "unacceptable".

Diamond will have half of his £2.7m share award for 2011 linked to the return on equity in three years' time. Only if the bank's return on equity is greater than its cost of equity (11.5%) will he take that half of the bonus. The same will apply to the £1.8m bonus awarded to finance director Chris Lucas. Until now, neither bonus had any performance criteria attached and would have been released, in shares, to both directors in three years' time.

The bank immediately won round Standard Life, which owns 2% of Barclays shares. Guy Jubb, the investor's head of corporate governance, said: "We now intend to support the remuneration report at next week's AGM."

However, it was far from clear that other investors had been convinced so easily and Barclays could face a tense week while shareholders lodge their votes not only for the remuneration report but also for the re-election of Alison Carnwath, the non-executive who chairs the remuneration committee. "Some are tempted to shift but most are not," one shareholder said. "It's a bit late to be doing this if the company thinks this is such a good idea - and also it does not address the fundamental issues on pay."

Investor advisory body Pirc kept its recommendation to vote against the remuneration report and Carnwath's re-election, arguing there should have been no bonus at all given the bank's performance. David Paterson, head of corporate governance at the influential National Association of Pension Funds, said it was a "positive step" but called on Barclays to "engage with shareholders after the AGM in order to address the fundamental concerns which many have about the structure of executive pay".

The Association of British Insurers, whose members control a fifth of shares on the stock market, declined to comment on the changes. Last week it issued an "amber top" alert to its members, highlighting its concerns about the bonuses of Diamond and Lucas. The ABI had previously pointed out that it was "business as usual" at the bank as the amount of revenues it had used to fund bonuses at Barclays Capital had remained static at 35% even though the bank had insisted bonuses were down 25% on the year.

The bank appeared to attempt to address this, saying that it was "fully committed to ensuring that a greater proportion of income and profits flow to shareholders notwithstanding that it operates within the constraints of a competitive market".

Barclays added that it had made no changes to the tax arrangements.

Lib Dem peer Lord Oakeshott said: "This shouldn't be enough to let them off the hook. What really sticks in the throat of taxpayers and investors is the blank cheque to cover his tax bills after his move from New York to London."

The changes followed week of shareholder meetings led by chairman Marcus Agius and were "recognising the strength of opinion expressed by some shareholders, via those meetings, and the executive directors' confidence in the future performance of the bank", Barclays said.

Sticking to its target for a 13% return on equity, the bank said: "Achieving this target of 13% return on equity will allow the portion of post-tax profits that are distributed as dividends to normalise at a level much higher than today, and Barclays intends to continue to make steady progress towards that as the return on equity improves. The combination of higher earnings and a higher dividend payout ratio will allow a significant increase in the absolute level of dividends received by shareholders".

Barclays Chief Bob Diamond Links Part Of Bonus To Improved Performance | Business

at the other end of the trough .....

At some point in the future, historians will look back at this era as the time when America basically lost its collective mind.

The latest example is Ted Kelly, the recently retired chief executive officer of Boston's Liberty Mutual insurance company. Ask any official or business person across the state, and they'll sing Ted Kelly's praises: good guy, insanely smart, devoted to the common cause, all of that manifest in that Liberty Mutual grew at breakneck speed under his leadership and gave millions of dollars away.

There's something else, though, that came out this week. Mr Kelly had an annual compensation package of $US50 million for the past four years. Yes, there's a zero after the 5. That's just shy of a million dollars a week, $192,000 per working day, $24,000 an hour. To run an insurance company.

It calls to mind an anecdote in an award-winning Washington Post series last year. A newly promoted chief executive of Dean Foods got a pay package in the 1970s equal to $US1 million in current dollars, plus a Cadillac. He moved from a three-bedroom house into a four and joined the local country club. He declined future raises because he thought it would be bad for company morale.

It's not apparent that Mr Kelly had those same reservations. As a result, every Liberty Mutual policyholder, all those regular people making ends meet at kitchen tables, have paid for Mr Kelly to take $200 million out of the company, their company, over the past four years.

Every Massachusetts taxpayer is footing part of his salary, given that the state granted Kelly's company a $46.5 million tax break for a new headquarters in Boston. The whole thing is grotesque.

This is not a screed against the rich. There are precious few people who don't want to be part of that group. But there should be at least some rhyme or reason to who makes what. You're an entrepreneur, inventor, someone who founded a business taking enormous risk, you deserve what the open market will pay.

It's why there's admiration (and envy) rather than ill-will for the techie who made $400 million from the sale of Instagram. But $50 million to be an insurance executive, albeit a very good one? Was there no one else on the planet who could do it nearly as well for $10 million?

These boards, of course, are the real problem. Mr Kelly revealed this week that the Liberty Mutual directors are paid $200,000 a year, a figure never previously reported.

Enter NStar chief executive Tom May, a marquee character in the serial of overpaid executives. Mr May sits on the Liberty Mutual board, helping to set Mr Kelly's salary.

Meantime, a key Liberty Mutual official sits on the NStar board, which recently hiked Mr May's pay from $7.9 million to $9.2 million.

This isn't fair market value; it's a rigged game: executives hurling bundles of money at each other, then using the raises as benchmarks. Is there a synonym here for grotesque?

Corporate profits set a post World War II record last year, but workers' pay fell 2 per cent. Chieftains are swimming in millions while unemployment is historically high. We're in an era of princes and paupers, mansions and minions, with income inequality in the US rivalling developing countries such as Uganda and Cameroon and tax policies that favour the ueber-rich.

This article was first published at the Sydney Morning Herald