Search

Recent comments

- economy 101....

56 min 28 sec ago - peace....

1 hour 44 min ago - making sense....

4 hours 23 min ago - balls....

4 hours 26 min ago - university semites....

5 hours 14 min ago - by the balls....

5 hours 28 min ago - furphy....

10 hours 43 min ago - nothing new....

11 hours 15 min ago - blood brothers....

12 hours 13 min ago - germanic merde....

12 hours 17 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

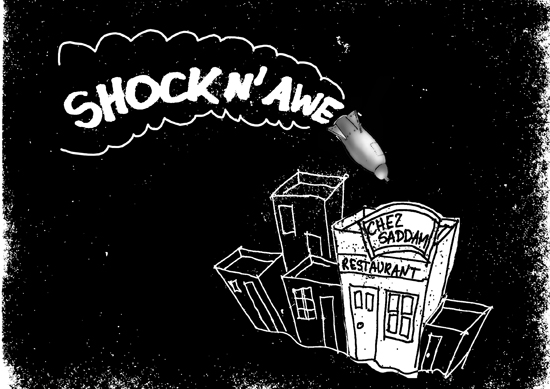

from the vault — shock and awe...

- By Gus Leonisky at 19 Dec 2010 - 9:55am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

wolfo... meister puppeteer...

the other motive for war...

Hersh's attempts to link the religious groups to the Pentagon, meanwhile, brought a denunciation from Catholic League President Bill Donohue, who said Hersh's "long-running feud with every American administration - he now condemns President Obama for failing to be 'an angry black man' - has disoriented his perspective so badly that what he said about the Knights of Malta is not shocking to those familiar with his penchant for demagoguery."

Further, Pentagon sources say there is little evidence of a broad fundamentalist conspiracy within the military. Although there have been incidents in which officers have proselytized subordinates, the military discourages partisan religious advocacy.

Hersh said Thursday that he couldn't remember every detail of his speech because it was "a rumination" rather than a scripted talk. But, he said, "no one said the whole war was waged as a crusade. My point is that some leaders of the Special Forces have an affinity for that notion, the notion that they're in a crusade.

"I'm comfortable with the idea that there is a great deal of fundamentalism in JSOC. It's growing and it's empirical. . . . There is an incredible strain of Christian fundamentalism, not just Catholic, that's part of the military."

He called his "angry black man" comment about Obama a "figure of speech, a cliche" that his audience, consisting primarily of American expatriates, laughed at. The speech was sponsored by Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service, which has a campus in Qatar.

Over a long and distinguished career, Hersh, 73, has broken dozens of major stories about the U.S. military, foreign policy and covert operations. In 1969, he exposed an Army massacre of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai and subsequent coverup, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize. His account of the Abu Ghraib prison abuses in Iraq for the New Yorker in 2004 spurred reform and prosecutions and brought Hersh new acclaim.

Hersh declined to comment on some of the specific statements he made in the speech, such as the notion that American military officers pass "crusader" coins among themselves. "I said what I said," he responded. "I can't get into it because I'm writing a book" about the small group of neoconservatives who directed U.S. foreign policy in the Bush administration.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/01/20/AR2011012006090_pf.html

see toons above...