Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

vale the mungo who laughed...

Mungo MacCallum always treated readers respectfully by announcing his allegiance to the Left. Most importantly he always had a sense of humour and expected this in others.

When Gough Whitlam asked who this ‘tall, bearded descendant of lunatic aristocrats is’, MacCallum mentioned great uncle Darcy Wentworth ‘bigamously married to a chambermaid by a bribed priest in a hot air balloon floating over Watsons Bay’ and praised uncle Billy Wentworth who advocated for the 1967 referenda on Indigenous rights. The MacCallums were less flamboyant. Great grandfather Mungo was Chancellor of the University of Sydney and the writer’s father was a journalist who produced the first television programs for the ABC.

MacCallum did not overestimate his own influence and admitted his ‘faults’. At school he fainted and so unlike Prime Minister Menzies was unable to see the Queen passing by in 1954 and begs understanding for securing bail for Paddy McGuinness after an anti-apartheid rally. Experience in a British election convinced him of the merits of compulsory voting and he decided that a writer had a responsibility to make readers interested in public affairs. What he embraced as the ‘method in his madness’ was a determination to entertain and to foreground the fun in politics.

Mungo was caught in a ‘bind’ during the ‘glorious false dawn’ of 1972. Iconoclasm loses its appeal when your icon is the prime minister. Despite his involvement in Labor’s campaign, Malcolm Fraser offered Mungo a speechwriting job. Mungo admitted that some of his memories were a little hazy but the sixties and seventies were a long time ago and the milieu of the long lunch could have clouded his memory. Nevertheless, mention of slogans such as ‘All the way with LBJ’ and chants such as ‘Lynch Bury, Bury Lynch’ will take the reader back.

Mungo filled a void for students of politics who research the constitutional issues of 1975 but neglect the social and political nature of the time. Mungo foregrounded the innate conservatism of the electorate, its distrust of the Left and its willingness to forgive those ‘born to rule’.

When Whitlam was sacked, Mungo was listening to a recording of his own ditty ‘nothing could be crazier than Malcolm Fraser grazier this morning’. Initially, he refused to believe what had happened but when he saw Laurie Oakes running, he realised ‘something apocalyptic had happened’. Both Whitlam and MacCallum burnt out too quickly but MacCallum reckoned he would not be tempted back to writing. Publications such as Nation Review were gone and the Australian changed dramatically.

Significantly, Juni Morosi was the only woman to get a mention, and Mungo reckoned the ‘shiny bum’ bureaucrats had it all over the bumbling politicians in those days. Mungo always observed that human weakness was an inevitable feature of democracy.

MacCallum stirred nostalgia but had a serious civic purpose. By demystifying politics and making it appear entertaining, he encouraged readers to take an interest. This memoir could even stimulate idealistic young Australians to ask whether some aspects of politics that have disappeared might be worth further consideration. In an age deprived of historical perspective, it is easy to imagine that politics has always been the same. But today’s cynical political style would benefit greatly from an injection of genuine humour.

There could be no better cure for the neuroses threatening our political culture than a dose of Mungo’s compassion, tolerance and humour. To the extent that political leaders are of us and from us, when we laugh at them, we laugh at ourselves. Life is brief and we need to laugh. When Mungo began writing for P&I his sign-off was simply ‘Mungo MacCallum is … Mungo MacCallum’. He was unique.

Read more:

https://johnmenadue.com/tony-smith-anyone-laughing-has-not-heard-the-news-vale-mungo/

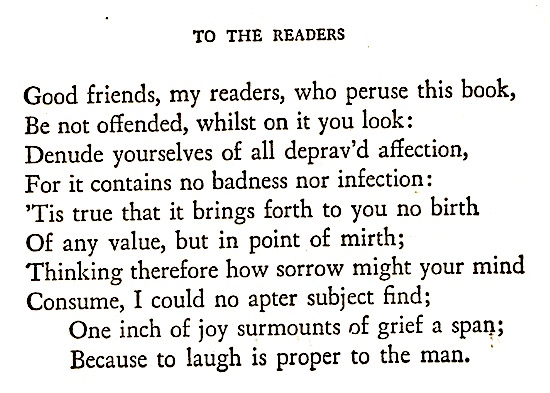

Image at top from a translation of Rabelais introduction to Pantagruel (16th century)...

- By Gus Leonisky at 11 Dec 2020 - 9:29am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

9 hours 36 min ago

14 hours 38 min ago

16 hours 58 min ago

18 hours 27 min ago

18 hours 35 min ago

21 hours 35 min ago

22 hours 4 min ago

22 hours 49 min ago

23 hours 20 sec ago

1 day 9 hours ago