Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

fak'n it ...

Could you explain to me this custom?” We had spent three days with our Turkish colleague, and by our final evening together in Çanakkale, on the eastern shore of the Dardanelles strait, the conversation had become more expansive. “Why do Australians insert newspaper into their backsides and set fire to it as they leap into the sea?”

Confused, we asked where on earth he had witnessed such an exotic cultural practice. “Right here in Çanakkale, many years ago. All of them completely naked, taking turns to jump off the jetty. They assisted each other with the newspaper and matches.”

His memory harked back to the late 1980s, a time when the backpacker “pilgrimage” to Gallipoli was in its infancy, before the torrent that was to follow. The Australians in question had been touring the battlefields between bouts of boozing and incendiary bathing, and their outlandish behaviour was widely frowned upon by their hosts. Reports appeared in local papers and, perhaps inevitably, spontaneous brawling erupted with local youths who took it upon themselves to police the boundaries of decorum.

Such a spectacle seems entirely incongruous today, and would embarrass the majority of Anzac tourists, whose journeys are more reverent and restrained. Yet the episode had lodged in our friend’s mind as an Australian “custom”. He told of other incidents of contemptuous conduct and deliberate disregard, not out of moral indignation but more as a historical curiosity. He explained that the annual sleep-out at Anzac Cove in those early years intrigued the local community, fuelling rumours of drunken orgies and general debauchery on the shores of Ari Burnu.

We had come to the Gallipoli peninsula in early May, only weeks after the centenary of the Anzac landing. Remnants of the production were being dismantled: the scaffolding of grandstands at Lone Pine stacked in piles near the cemetery; the pilgrims’ handwritten letters to “the fallen” still stuck to the gravestones of Australian soldiers at Anzac Cove. With the enormous video screens, loudspeakers and thousands of participants gone, the landscape had returned to some semblance of normality.

Unlike the Anzac landings in 1915, the invasion of 2015 was marked by Australia’s “friendship” with the Turkish people. This sentiment has recently become a pillar of the Anzac legend, both for Australians and their former enemies. Shorn of the horror of combat, the friendly wartime encounters – foes burying one another’s dead, soldiers sharing cigarettes or singing across the trenches – have become integral to our understanding of what took place a century ago. Tales of Turkish–Australian friendship are repeated out of all proportion to the number of times the events actually occurred.

All across the peninsula – in monuments, museums, souvenirs, and even on the floor tiles of one popular local restaurant (which shows a khaki-hatted Australian tourist shaking hands with a Turk) – this narrative exalts the camaraderie of the two nations.

Gentleman’s War is the portentous title of one locally sold guidebook, conveniently recasting Gallipoli in a pacifist guise. Another Turkish publication claims that Simpson and his donkey would often rescue wounded Turks. Official battlefield tours emphasise the comradely nature of the conflict and the absence of any deeply felt enmity – a message largely reserved for the Anzac sector rather than the British, Irish and French battlelines to the north and south. Some historians continue to cultivate this perception.

Days before centenary events, the Australian Financial Review told of Australian historian Les Carlyon “puffing” his way up the hills of Gallipoli with his Turkish counterpart Kenan Çelik. Asked what Anzac meant to him, Çelik enthused, “it’s the message of Christians and Muslims embracing”. Carlyon was equally determined to peddle a sentimental view. He recounted that when an armistice was declared in May 1915, allowing both sides to bury their dead in no man’s land and speak to their adversaries, a “change” occurred in the Australian soldiers’ diaries; they started writing things like, “These Turks aren’t bad blokes.”

As with so much Gallipoli mythology, this particular strain has its origins in the all-seeing eye of Australian war correspondent Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean. “It is extraordinary how the men have changed in their attitude to the Turks,” he noted in his diary after the May armistice. “Since the slaughter of May 19th … they have changed entirely. They are quite friendly with the Turks.” But this was not the whole story. Bean was equally frank in recording mutual distrust during the ceasefire, with the Australians repeatedly firing on Turks caught collecting rifles and reconnoitring the Anzac trenches. He glumly concluded, “This quite disillusioned me as to truces … I don’t think I would ever desire a truce again.” Bean’s later diary entries show why we should be wary of tales of frontline fraternity. During one exchange of gifts, the Australians launched tins of bully beef onto the Turkish parapet with dubious intent. “When a Turkish hand appeared reaching for the tin they would blaze at it. On one occasion I believe they threw a ham bone over – an abhorrence to the Turks – and caused quite a disturbance.”

It is only more recently that the myth of mutual regard has gained such acceptance.

The Çanakkale Martyrs’ Memorial, for example, was originally opened in 1960 but it was not until the 1990s that a new frieze portraying a solemn scene of reconciliation was added. Here, Turkish soldiers are depicted bearing a wounded Anzac, while their officers warmly greet a slouch-hatted Allied soldier. The shoreline of Anzac Cove itself is adorned with an imposing sandstone edifice built in 1985, inscribed with the words now famously attributed to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Turkish republic:

Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives … You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours … You, the mothers, who sent their sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well. – Atatürk, 1934

Atatürk’s adage has become the defining motif of the redemptive myth, reproduced across the battlefields and featuring prominently in official commemorations. Yet as Paul Daley showed recently in the Guardian (drawing on the work of Turkish historian Cengiz Özakıncı), no credible source can be found that clearly links Atatürk to these hallowed words. The celebrated image of “Johnnies and Mehmets … side by side” seems almost certainly a latter-day invention concocted in a Brisbane suburb in 1978.

It was the Gallipoli veteran and former Queensland Country Party trustee Alan J Campbell who first ushered the celebrated passage into the Anzac liturgy. Charged with the task of erecting a fountain in Brisbane’s city centre to honour Gallipoli veterans, Campbell drew from an account shared with him by another veteran who had heard of Atatürk’s stirring speech during a visit to Gallipoli the previous year.

Although Campbell attempted to confirm the purported speech, no evidence was found. The Turkish Historical Society did send Campbell a newspaper interview with former interior minister Șükrü Kaya, in which he referred vaguely to sentiments apparently voiced by President Atatürk in the 1930s. Without confirming the source (and adding a few embellishments of his own, including the “Johnnies and Mehmets” phrase), Campbell nevertheless had the words transcribed onto a plaque adorning the fountain a few months after its inauguration in March 1978. In this way, hazy testimony and a contemporary creative flourish combined to produce an image far more in tune with the 1970s than the age of Atatürk.

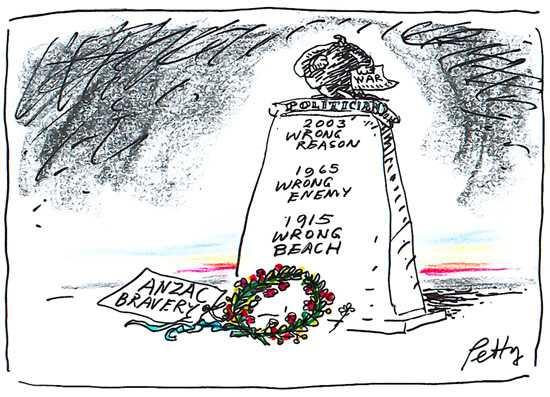

If there were any doubt that the purported history of the Gallipoli campaign – built on a midden of historical half-truths and outright falsehoods – had fallen prey to contemporary politics and commercialisation, the spate of centennial memorialisation and relentless Anzackery provided ample evidence. Last February, hundreds gathered in the Sydney municipality of Auburn, home to approximately 5000 residents of Turkish ancestry, for the unveiling of a 20-metre Wall of Friendship. The wall’s central plaque depicts a Turkish soldier carrying a wounded Allied soldier, a facsimile of a statue that the Turkish government erected in 1997 at Pine Ridge on the Gallipoli battlefields. Another plaque on the wall bears the crossed flags of Turkey and Australia, and Atatürk’s alleged words from 1934. For Auburn city councillor Semra Batik-Dundar, the structure represented “a story of compassion … [and symbolised] the love and friendship between the two countries”.

A few weeks later, at Goulburn in south-eastern New South Wales, the Pine Ridge statue found another incarnation. In a light-and-video installation, the Turkish soldier carrying an Allied soldier (“probably an Anzac”) was one of several images beamed onto the face of the regional city’s Rocky Hill War Memorial. The installation temporarily obscured the original memorial’s modest statement of remembrance, replacing it with emotive images of war and the camaraderie of the combatants. In the government-funded Australian Turkish Friendship Memorial Sculpture unveiled in Melbourne last April, which also bears Atatürk’s supposed words, the memorialisation of war has also given way to a redemptive story that could be used to foster multicultural community spirit. This sentiment, although admirable, is being built on shaky ground: the much-lauded statue of the Turkish soldier carrying his enemy is entirely bogus.

According to Turkish authorities, the Pine Ridge statue symbolises the “courtesy and consideration that developed on both sides” and the “humanistic attitude” of the Turkish soldiers. It is a popular stop for visitors and locals alike. Subsidised by the Turkish government, companies bussing Turkish school students and tour groups invariably halt at the statue and proclaim the statue to be an emblem of national character: the Turkish Samaritan who nobly spirited his enemy to safety.

When the statue was first unveiled, the inscription (also translated into English) claimed that, during a ceasefire after “heavy trench fighting” at Chunuk Bair on 25 April 1915, the cries of a wounded Allied captain could be heard from between the lines.

The plaque read:

At that moment an incredible event occurred. A piece of white underwear was raised from one of the Turkish trenches and a well-built, unarmed soldier appeared. Everyone was stunned and we stared in amazement. The Turk walked slowly towards the wounded British soldier, gently lifted him, took him in his arms and started to walk towards our trenches. He placed him down gently on the ground near us and then straight away returned to his trench … This courageous and beautiful act of the Turkish soldier has been spoken about many times on battlefields. Our love and deepest respect to this brave and heroic soldier.

The account was attributed to First Lieutenant Richard Casey. His words were said to have dated from 1967, when he was Australia’s governor-general. Casey accompanied the Australian Imperial Force’s 1st Division when it landed on 25 April 1915 and was purportedly an eyewitness to this remarkable scene. The story has been repeated for years in guidebooks and newspapers, including Sydney’s Daily Telegraph in November 2013: “In 1967, Governor-General Lord Richard Casey arrived in Turkey to inspect the abandoned battlefields dotted along the west coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula … where he gave a speech recounting a remarkable story from the campaign.”

The problem, and not the only problem, is that Casey was never in Turkey in 1967.

That year he visited England, the US, India and Papua New Guinea. Nor is there any public record of him visiting Turkey as governor-general, or giving any speech at any time in which he recounted such a story. Casey’s biographer, the meticulous scholar WJ Hudson, makes no mention of it. And although Casey kept a detailed diary during his time at Gallipoli in 1915, nowhere within his personal account is there anything that even vaguely resembles the episode eulogised at Pine Ridge today.

But there are more obvious inconsistencies: there was no “heavy trench fighting” on 25 April 1915 (the diggers weren’t dug in yet), nor indeed any fighting at all, let alone a ceasefire, at Chunuk Bair that day; the story claimed that the Turkish soldier was “unarmed” yet there he is, cast in bronze, with his rifle slung over his shoulder. It was all fabricated.

Keen to save face amid growing controversy, and desperate to retain the redeeming power of the story for Gallipoli’s booming tourism industry, Turkish authorities changed the inscription on the plaque. In the early 2000s, a new Turkish-language version appeared, which again put words into Casey’s mouth:

We left the Çanakkale Peninsula after having fought the Turks, losing thousands of heroes. In our battles we have realised and admired the patriotism of the Turks. Every Australian loves the Mehmetçik [Turkish soldiers] as their own sons. His bravery and his love of country and humanity have immensely impressed the Anzacs. With much respect and gratitude to the Mehmetçik – Australian governor-general Lord Casey

The new quotation appeared to deliberately echo Atatürk’s words, yet by the time Alan J Campbell set in train the Atatürk myth in 1978, Casey was already two years dead. Inexplicably, to add to the confusion, the English translation of the original plaque remained at the foot of the statue for several years before it, too, was removed.

Ultimately, none of this clumsy airbrushing mattered because the original story had taken flight. Reproduced on monuments, quoted in newspapers and guidebooks, and circulated online, the tale of the compassionate soldier has become too alluring and useful to expose as fiction. Although a handful of Turkish websites and guidebooks now acknowledge the story to be a fabrication, it continues to be recycled as a tale of Turkish benevolence and an emblem of close ties between the two countries.

From the moment Turkey first established diplomatic relations with Australia and opened an embassy in Canberra in 1967, the Gallipoli story became more visibly one of fraternisation. More than 300 Anzac veterans had already returned to Gallipoli in 1965 for the 50th anniversary. As they disembarked, they were greeted by a Turkish military guard of honour, Turkish veterans of the Gallipoli campaign, officials, journalists and local villagers. Turkey’s first ambassador in Canberra, Baha Vefa Karatay, a former brigadier and military history buff, was intent on furthering “the friendship and respect for the valour of each nation’s soldiers”. In April 1968 Karatay hosted a reception for 42 Gallipoli veterans at the Turkish embassy, which Casey attended. The two men discussed Casey’s memories of the Gallipoli campaign. Karatay already had plans for a book that gathered the recollections of both Australian and Turkish soldiers who fought at Gallipoli, hoping that the combination of the former enemies’ memories would reconcile the two nations and deepen ties in the years ahead.

When the book was finally published in Turkey in 1987, Karatay paraphrased what Casey had said to him 20 years earlier: “We Australians knew and loved you at Gallipoli,” Casey supposedly said. In another anecdote with some similarity to the Pine Ridge statue, Casey allegedly told Karatay: “One day we had to bear our wounded past a Turkish trench in open terrain. When five or six of us carried out the task, we were neither attacked nor fired upon from the Turkish trenches. The Turkish soldiers had lifted their heads from the parapet and watched in full humane understanding.” It’s not hard to see Karatay fuelling the patriotic fires, exaggerating Casey’s recollections to laud his countrymen and cement the bonds of Turkish–Australian friendship. While it’s possible that a creative interpretation of Karatay’s paraphrasing of Casey’s remarks was the source of the Pine Ridge statue, it still fails to match the heroic story memorialised in bronze, and conceals the true nature of Casey’s experience at Gallipoli in 1915.

Casey’s Gallipoli diary, which he kept from 25 April until 7 October, when he was evacuated to London with suspected enteric fever, reveals how quickly the horror and confusion of war overwhelmed him. Although he observed in May that there was “no personal animosity about war – men merely do their duty in fighting their government’s quarrel, and when that is done … they would just as soon give their enemy their last cigarette as give it to their friend”, Casey was under no illusion. “Our men treat the Turk more like a rabbit than anything else.” As the Turks charged the Australian lines, he was buoyed by his men’s call to arms: “We’ll give ’em Allah!” He described the stench of the decomposing bodies of the enemy as “Turkish eau de cologne”, and after a fierce day’s fighting on 19 May he could barely contain his elation when the Australians and New Zealanders had mounted a successful counterattack near Quinn’s Post: “The number of dead Turks is something wonderful – the slopes in front of our trenches are literally covered with Turks …”

At Gallipoli, Casey quickly realised the botched nature of the offensive, complaining that the Allies had waded into the campaign “with too few men” to achieve their objective of taking the ridges and securing the Dardanelles. Three weeks in, it was clear that he harboured severe doubts regarding the rationale of the operation. “This game gets very sickening. I get fits of rather severe depression at times. It all seems so hopeless and endless and sordid. Tied down to a few square miles of steep hilly country – plastered with shells from well concealed positions – no freedom to manoeuvre and no getting on.” Fifty years later his view was unchanged. As he wrote to the federal Liberal MP Bruce Graham on 24 March 1965, “We had no idea why we were there, but as war was an unaccustomed exercise anyhow we didn’t spend much time thinking about things that were beyond our ken.”

Any of the above remarks by Casey would be a more truthful evocation of Gallipoli than the myth depicted on the Pine Ridge statue. Fighting war creates a radically different set of imperatives to those elicited by remembering war. Returned soldiers struggle to forget the horror, and have to reconcile the suffering and loss of life, while their fellow citizens reach for stories of friendship to redeem the humanity of loved ones who fought.

In the heat of battle, the soldier rejoices at the sight of the enemy dead – they are “rabbits”, vermin who must be exterminated. For the Turks in 1915, our soldiers were no different. Even in 1931 Atatürk described the Allied forces as “invaders” and noted pointedly, “The history of civilisation will judge those lying opposite each other and determine whose sacrifice was more just or humane and who to appreciate more.” No stirring evocation here of the sleeping sons of mother Turkey, their differences dissolved in death.

Nothing exemplifies this cognitive dissonance more than the wartime diaries and letters of Private Alan J Campbell – the Queensland soldier who years later played a key role in popularising Atatürk’s dubious aphorism. Fully transcribed and accessible at the State Library of Queensland in Brisbane, Campbell’s day-to-day account of his four months at Gallipoli evokes at once excitement, anxiety, the occasional mourning of a fallen mate and a pervasive longing for news from home. His Gallipoli is a place of constant peril interspersed with bouts of boredom and dysentery. To the extent that the Turkish foe features at all, he is an adversary whose periodic advances are variously “repulsed”, “knocked about” and “easily cut up”. Campbell is calmly committed to killing his enemy. He relishes his “pretty exciting” role as a sniper, which he and his “spotter [Monty] both like very much as there is generally plenty of shooting to be done”. Of one particularly “cheeky” adversary he notes effusively, “My third shot just about carried his skull cap off and the part of his head in its way.” Another target “went through various funny antics on the skyline after he was hit”.

The Turks themselves seemed to entirely reciprocate these sentiments, frequently erecting signs in English such as “Say your prayers your life is short”. Campbell and his sniper colleagues busied themselves removing these statements with their periscope rifles, while their Turkish counterpart (who was “rather a sport”) signalled the extent of their misses. Lest this shred of shared endeavour be mistaken for a pervasive camaraderie, Campbell continues: “One day an old chap was waving me a miss with his hat and I got it with a bullet.” Indeed he is more attentive to describing Turkish outrages, such as shooting the Allied wounded as they crawled back to the parapet, or stealing the boots of deceased diggers. He notes indignantly how “one fellow fell right into the Turks’ trench and his stripped body was thrown over the parapet by the Turks afterwards”. Hardly a tribute to the “not-bad-blokes” of Carlyon’s account, Campbell’s personal records bear scant resemblance to the latter-day myth of cross-trench amity.

The stories of Turkish–Australian friendship at Gallipoli are repeated endlessly today as a means of ennobling the campaign for a generation uneasy with older myths of martial valour. We imagine the battle as the heroic birth of a nation, despite the fact that our soldiers did not understand why they were there in the first place. We remember tales of fraternisation and forget the overwhelming evidence of inhumanity, preferring our wars cleansed of killing. We feel connected to the story of Gallipoli but at the cost of historical understanding.

It is no coincidence that Australia and Turkey have invested more in the friendship narrative than any of the other nations that fought at Gallipoli. The Turkish government’s official recognition of the name Anzac Cove in 1985 at the request of Australia and New Zealand (Atatürk memorials were erected in Canberra and Wellington in a reciprocal gesture) marked the first of many joint initiatives designed to strengthen diplomatic ties and alleviate the stigma of a former enemy annually re-occupying ground conceded in December 1915.

Unsurprisingly, the surface camaraderie is periodically punctured by political and diplomatic differences. Prime Minister John Howard’s bungled attempt to include Gallipoli on the National Heritage List in 2003 was one prominent source of friction (as was his remark that the Gallipoli peninsula was “as much a part of Australia as the land on which your home is built”). Howard was merely echoing Prime Minister Bob Hawke’s wistful fancy that Anzac Cove was “a little piece of Australia”, but both statements underlined an endemic ambiguity about Australian proprietary claims to Turkish soil that could only rankle in Ankara. The infamous road dispute in 2005, in which the foreshore of Anzac Cove was despoiled to service the hordes arriving for the 90th anniversary, also sparked public recriminations between the two governments.

Undeniably, the new redemptive myth helps both governments cope with the demands of stage-managing an annual influx, which comes with unavoidable political undertones.

In 2002 there was only one Turkish tour company operating on the Gallipoli peninsula; today there are more than seven working alongside several Australian companies. For both Australian and Turkish tour groups, selling a “friendly war” is more palatable to customers, and ultimately far more profitable. As one company enthuses, its “Youth Tours … give young people the chance to explore their mutual ties to Gallipoli.

Australian and Turkish youths explore a shared history and the rich and rewarding bounty of international friendship.” Several Turkish websites declare confidently that “even on the field of the war the spirit of humankind [was] maintained above everything. A friendly attitude developed between Turks and Anzacs during the gentlemanly war.”

Since the early 1990s, when Australian “pilgrims” began descending on Gallipoli in larger numbers, Turkey, not to be outdone, has invested in a rash of monuments and actively encouraged commodification of the Gallipoli story as a heroic myth of national formation, albeit one increasingly clothed in Islamist propaganda, as Edward Luttwak recently noted in the London Review of Books. “Today’s Islamist rulers are doing everything possible to obliterate [Atatürk’s] firmly secular Turkey … the official centennial documentary of his victorious Gallipoli campaign featured a fervently praying [President] Erdoğan as well as re-enactors mouthing Islamic invocations while [Atatürk] himself only flashed by as a silent image.” Turkey’s deliberate cultivation of the Gallipoli story as a sacred parable, complete with injections of government funds as in Australia, has resulted in a political climate in which the official narrative is not open for debate. Forging a conciliatory bond with the former enemy subtly facilitates this, closing ranks against the prying eyes of political dissent.

Unknown to those who embrace it, the tale of a Turkish soldier carrying a wounded Australian at Gallipoli can indeed be found in the archives, but its origins lie in a completely different source to the one etched on the statue at Pine Ridge. On 10 November 1918, Private BJ Dunne of the Australian Imperial Force’s 16th Battalion recalled his experience as a prisoner of war at Gallipoli.

I was taken prisoner on or about August 8th 1915 at Anafarta after being wounded in the leg … A Turk took me or rather found me lying out and I might say that that man was the means of saving my life twice, for two other Turks tried to kill me and he stopped them each time, [he] also took one man’s water bottle … and gave me a little water … After some time this same man carried me on his back a very long way under fire and put me under a tree, this I think was their hospital.

Dunne’s evidence could easily be leapt on by proponents of the Turkish–Australian friendship story as proof that the myth is based on historical truth. But when the full context of his statement is taken into account, it’s possible to appreciate why we should be cautious about elevating such stories. Dunne described his “shocking” treatment at the hands of the Turks in the days following his capture. He watched as one of his fellow Australians, dreadfully wounded in the back, was forced to walk; when he fell to the ground his captors “struck him and treated him badly”. The Turkish soldiers continued this harsh treatment, while the women Dunne encountered “spat at us and pelted us with all kinds of muck”. Not until he reached a hospital in Constantinople and was out of the hands of the military did the Turks treat him with any degree of humanity.

On the back of one Turkish soldier and the comforting words that Atatürk never uttered, Turkey and Australia have rushed to memorialise a romantic image of Gallipoli – one of co-operation and friendship. As admirable as these intentions might be, they are based on falsehoods and the misrepresentation of war. Far better a friendship that has the courage to confront war’s brutality, and the senseless loss of life that occurred in 1915.

An Anzac myth: The creative memorialisation of Gallipoli

- By John Richardson at 12 Jan 2016 - 10:57pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

16 min 41 sec ago

9 hours 39 min ago

10 hours 32 min ago

13 hours 33 min ago

14 hours 47 min ago

14 hours 53 min ago

3 days 21 hours ago

3 days 22 hours ago

3 days 23 hours ago

3 days 23 hours ago