Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

on being screwed .....

We are taught that the laws of the market are as certain as the law of gravity, that capitalism is the natural order of things and that the system generally works. But while a tiny few are doing very well out of capitalism, the vast majority face a day-to-day struggle for survival.

More than a billion people live on less than a dollar a day and 6 million children die each year of hunger-related illness. Of the 4.4 billion people in developing countries, nearly three-fifths lack access to safe sewers, a third have no access to clean water, a quarter do not have adequate housing, and a fifth have no access to health services.

In the United States income inequality is at levels even higher than those in ancient Rome. According to a 2011 study by two American historians, the top one percent of earners in Ancient Rome controlled 16 percent of the society's wealth. By comparison, the top one percent of American earners controls 40 percent of the wealth.

The wealthiest one percent saw their incomes rise by 275 percent between 1979 and 2007, according to the US Congressional Budget Office. Just six billionaires – the heirs to the retail giant Walmart – possessed the same amount of wealth in 2007 as the bottom 30 percent of Americans.

This stark inequality is reproduced on a global scale.

According to the World Wealth Report 2012, the world's richest 1 percent owns nearly half of the world's wealth, while half of the global population own just 1 percent of the world's wealth. And, according to Forbes Magazine, the world’s 1,226 current billionaires hold a combined wealth nearly four times the combined GDP of sub-Saharan Africa. Last year, according to the aid organisation Oxfam, they earned enough money to end world extreme poverty four times over.

Australia, buffeted by a decade-long mining boom, has not escaped the global increase in inequality. The richest 20 percent of Australians possess 61 percent of the nation's wealth, while the poorest 20 percent share just 1 percent of Australia’s wealth. Today, 2.2 million Australians (1 in 8 households) live below the poverty line, according to the Australian Council of Social Services, and more than 105,000 are homeless (1 in 200 Australians).

Why is the world so unequal?

Competition between capitalists has created a constant drive for innovation unheard of in previous class societies. There are enough resources today to provide everyone with adequate food, shelter, education and sanitation. In fact, humanity's productive capacity and knowledge is so developed that it opens the possibility of a massive leap forward in science, art, culture, environmental sustainability and human solidarity.

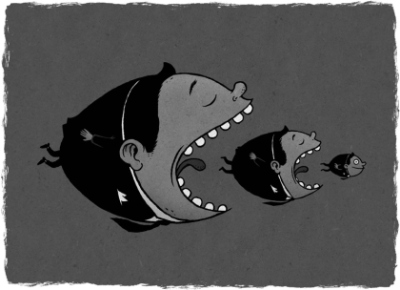

But under capitalism, land, natural resources, machinery and factories – the “means of production” – are owned by a small minority of people, the capitalist class. The majority, the working class, must sell their labour to the capitalists in return for a wage or salary. We are told this is “fair”. But the goods and services produced by workers are then sold by the capitalists for more than the cost of wages he or she pays. This is what Marxists call exploitation. Capitalists live off the profits and reinvest the rest for the further accumulation of wealth.

Like everything else for sale under capitalism, our capacity to labour is a commodity; its price subject to fluctuation according to the laws of the market. In fact, capitalism seeks to turn everything of value into a commodity: the house we live in; the food we eat; even the water we drink. Goods and services are not produced in our society to satisfy people's needs, but rather to be sold for a profit.

This “profit motive” is not simply the result of greed on the part of individual capitalists. They have little choice in the matter. Capitalists must make a profit to maintain their investments and to avoid going broke. Competition with other capitalists forces them to reinvest as much of their profits as they can afford to keep their means and methods of production up to date and consequently to pay as little as they can in wages.

In the eyes of the capitalists, wealth is wasted if it is used for anything other than increasing profits. As a consequence, the immense wealth generated under this system is concentrated in ever fewer hands.

The rise of global corporations

The growth of global inequality coincides with the rise of giant transnational corporations. Of the 100 largest economies in the world, 52 are corporations and 48 are countries. The largest of these corporations, Exxon-Mobil, increased its revenue in 2011 by 28 percent to US$453 billion (more than the GDP of South Africa). Seventy percent of world trade is controlled by just 500 of the largest industrial corporations.

In the early twentieth century, the rise of transnational corporations coincided with the dividing up of the world's markets by the colonial powers. The first capitalists were merchants who traded in commodities, including spice, cloth and slaves. They moved beyond simply “buying low” and “selling high” to become exploiters of labour. Initially they engaged artisans to work in homes and scattered workshops. With the advent of the industrial revolution in Britain in the late eighteenth century, workers were brought together under one roof in factory sweatshops.

To achieve this transformation of production, two developments were required: the amassing of fortunes to build large, capitalist enterprises and the availability of a mass labour force. The first was achieved through the conquest of the riches of the colonies. The second was achieved by driving peasants off their land.

In Capital, the German revolutionary Karl Marx described how the Europeans' plunder of the Americas, and the spread of colonies, greatly boosted commerce and industry at the expense of the colonised:

“The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the indigenous population, the beginnings of conquest and plunder of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for commercial hunting of black-skins, are all things which characterised the dawn of the era of capitalist production.”

In England, as the industrial revolution unfolded, a new class of wage workers came about through the theft of common lands that peasants had depended on for their livelihood. The English landed gentry simply “enclosed” common lands, claiming them for sheep pastures so that they could sell wool to the newly emerging cotton mills. Peasants were forced from lands they had tilled for centuries by soldiers and driven into the cities in search of employment.

As industrial production has shifted from Europe and North America to the former colonies, this process has been repeated on a much larger scale. As US author Mike Davis observed, in his book Planet of Slums,

“The scale and velocity of Third World urbanization, moreover, utterly dwarfs that of Victorian Europe. London in 1910 was seven times larger than it had been in 1800, but Dhaka, Kinshasa, and Lagos today are each approximately forty times larger than they were in 1950”.

According to the UN, more than one billion people now live in the slums of the cities of the South. Warehoused in shanty towns, these urban slum-dwellers have been forced to seek out a miserable existence in the informal economy.

Whilst the private armies of the landed gentry drove English peasants off their lands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, mass urbanisation in the Third World has been driven by the forces of corporate globalisation. A worldwide debt crisis beginning in the late 1970s, and subsequent “structural adjustment” programs imposed on the Third World nations by international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, saw billions driven off their lands and into deeper poverty to raise profit margins for the world's global corporations.

Today, the colonialism that coincided with the rise of capitalism has given way to a neo-colonial world order, in which the transnational corporations' control of technology and finance is buttressed by trade blocs and military force.

War: capitalism with the gloves off

The rise of capitalism as a world system has seen more wars fought than ever before. Nearly 100 million people perished in two world wars during the first half of the twentieth century as the imperial powers of Europe battled it out for control of colonies and strategic markets.

Killing people on a mass scale has been refined to a science. Capitalism has given us the atomic bomb, which killed hundreds of thousands in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and land mines and cluster bombs, which kill and maim long after the shooting war has finished. Today, twenty years after the end of the Cold War, a nuclear arms race continues, threatening to wipe out the human race.

Just as capitalist governments use police against protesters and to break strikes in industrial disputes, powerful imperialist states use their militaries to intervene in underdeveloped countries where the investments of multinational corporations are threatened by outbreaks of popular struggle. In his 1933 book, War is a Racket, retired US Major-General Smedley Butler reflected on his 33 years of military service in the Marine Corps:

“I spent most of my time being a high-class muscle-man for big business, for Wall Street and for the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico... safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place of the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. The record of racketeering is long.”

Since the Second World War, the US has emerged as the world’s dominant power. Today it uses vast military might to exert its global domination through various means – including wars of occupation (Iraq and Afghanistan) and arming client states (such as Colombia and Israel).

The “War on terror” has provided the pretext for much of the slaughter. Where a fig leaf of international diplomacy is required, the UN Security Council is invited to endorse such imperial conquests. Reliable US allies, such as the NATO powers and Australia, are also brought in to fight alongside US marines to provide a veneer of “international support”. Indeed Australia has joined US forces in numerous imperial conquests since World War II, including Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Wars, which pit working people against each other, provide a means for multinational corporations, with the backing of imperial states, to defend and extend their market share with the threat – or use – of violence. New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman aptly explained the relationship between the free market and war to his readers back in 1999:

“The hidden hand of the market will never work without a hidden fist – McDonald's cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the F-15. And the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley's technologies to flourish is called the US Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps.”

Environmental devastation

The rise of global capitalism has also put the future survival of humanity at risk from environmental vandalism. Forests have been felled, soil exhausted, rivers dammed and species made extinct in the eternal hunger for profits. The burning of fossils fuels has produced an increase in green house gases. Global warming continues to accelerate.

Faced with the overwhelming evidence of climate change, capitalist governments have been forced to acknowledge that action is required. Yet the solutions they put forward remain little more than smoke and mirrors.

We are told that nuclear power is safe, despite the disasters of Fukushima and Chernobyl, which forced hundreds of thousands from their homes and will result in cancer fatalities for decades to come.

The centre-piece of the Australian government’s 'environmental' policy is a carbon trading scheme that gives business the opportunity to purchase pollution rights. Under their scheme, coal-fired power stations can continue to pollute, provided they subsidise carbon-offsets, based on the logic that their carbon emissions will be absorbed from the atmosphere by planting some more trees.

Carbon trading schemes, which have been operating in Europe for more than a decade, have proved disastrous. While consumers are slugged for the costs faced by the polluters, little is being done to make the necessary transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. This is because global corporations, which exercise control over the supply of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas, don't want to see their profit margins dinted by a ready, affordable supply of energy from renewable sources, such as wind and solar farms.

There can be no 'market solutions' to the environmental crisis we face. We cannot create clean air by privatising the very air we breathe. Yet the technology exists to meet our energy needs sustainably with renewable sources and greater efficiency.

A system in crisis

Today economic crisis has pushed twenty-six million European workers into the dole queues. In Spain, Greece and Portugal more than one in five workers, and half of young people, are out of work. In the Middle East and North Africa, mass unemployment among graduates and stifling repression has sparked the Arab Spring, a series of uprisings that have seen dictators fall from Tunisia to Egypt and Yemen.

The crisis is not simply about debt and poor financial regulation. Nouriel Roubini, a professor of economics at New York University put it like this in the Wall Street Journal in 2011:

“Karl Marx had it right. At some point capitalism can self-destroy itself… We thought that markets work. They are not working. What’s individually rational…is a self-destructive process.”

The current crisis in Europe and North America was precipitated by a housing bubble. In the early 2000s houses prices soared, but wages did not. Banks offered loans knowing that borrowers would not have the capacity to pay. As a construction boom – financed by shonky loans – came to a grinding halt, shareholders panicked. Banks stop lending, economic growth came to a standstill and workers began to lose their jobs.

Today, 500 Spanish families are being evicted from their homes every day, while thousand of newly built apartment blocks remain empty. Some, without jobs and unable to pay their mortgages, have thrown themselves from balconies, rather than face the bailiff knocking at the door.

One after another European government has imposed harsh austerity to bail out the big end of town. As Greek economist Costas Lapavitsas observed last year, “The hour has come to pay the piper, and ordinary citizens across Europe are growing to realise that socialism for the wealthy means punching a few new holes in their already-tightened belts.”

Wages, pensions and unemployment benefits are being cut, teachers and public servants are being sacked, hospitals and public utilities are being privatised. But these measures are taking place in the face of fierce resistance. Last November, millions of workers across southern Europe brought industry to a standstill in simultaneous general strikes.

There is an alternative

The inequality and injustice of capitalism, the pollution of our environment, the invasion and occupation of nations that refuse to follow the script, and mass unemployment, are not the aberrations of a system that needs tinkering. They are how capitalism works.

Capitalism is based on a profound contradiction. Whilst tremendous advances in labour productivity under capitalism have produced wealth enough to wipe out hunger and poverty, it remains a system subject to profound crises that have thrown millions out of work, sparked brutal wars of conquest and impoverished the majority of the world's population.

Capitalism has brought masses of workers together in factories, mines, warehouses and offices, as capitalist production methods have spread throughout the world. A global working class has been born, the largest social class in human history. Yet workers have no control over the character and conditions of their work. Labour for capitalists is but a means to expand profits. For workers it is solely a means to make a living.

Imagine a society where the means of production are held in common, for the common good of humanity. Instead of goods being produced only if they can be sold for a profit, they are produced because they are socially necessary; their production and distribution carried out according to a plan devised democratically by workers themselves.

Imagine a society where “overproduction” is not the trigger for a crisis that produces mass unemployment, but rather a means to reducing the hours of work demanded of each worker.

Imagine a society where people take what they need and give what they can; where no one is satisfied until everyone has food, clothing, shelter and quality of life.

Imagine a society that no longer pitted workers against each other, in competition for work; where war, famine, poverty, racism, sexism and homophobia were things of the past.

There is an alternative to the irrationality of capitalism. That alternative is socialism.

Socialism is not a new idea. But today, socialism is possible as it never was before because capitalism has created the material conditions and social forces necessary to bring about the abolition of class society. As Marx observed, capitalism has brought into being its own “gravediggers”: a growing working class with the power to overthrow the capitalist ruling class. Marx's lifelong collaborator Friedrich Engels wrote in 1877 that,

“the bourgeoisie, a class which has the monopoly of all the instruments of production and means of subsistence, but which in each speculative boom period and in each crash that follows it proves that it has become incapable of any longer controlling the productive forces, which have grown beyond its power, a class under whose leadership society is racing to ruin like a locomotive whose jammed safety valve the driver is too weak to open. If the whole of modern society is not to perish, a revolution in the mode of production and distribution must take place, a revolution which will put an end to all class distinctions.”

The words are as true today as they were when they were written. But such a revolution won't come about by us wishing and waiting. We need to fight for change. Socialism – a society that organises production to meet human need, not corporate greed – is not only possible, but urgently necessary.

- By John Richardson at 23 Feb 2013 - 4:42pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

15 min 55 sec ago

9 hours 55 min ago

12 hours 52 min ago

15 hours 11 min ago

1 day 51 min ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 8 hours ago

1 day 12 hours ago

1 day 14 hours ago

1 day 14 hours ago