Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

someone has to do it ...

It’s 5 am on a pitch-black inner Melbourne street. Two small children are sleeping inside a weatherboard house as their mother, the lawyer and corporate activist Shen Narayanasamy, creeps into a taxi and asks the driver to hurry to the airport. She’s late, and puzzled by a faulty alarm clock. But over the past few nights she hasn’t slept much. She’s been adding the final touches to a report on Transfield Services, the company that manages Australia’s offshore detention program, and its alleged complicity in human-rights abuses.

The car winds through the dark streets and Narayanasamy doesn’t mind being one of the few awake. She spent nights drafting the report during her recent maternity leave. “You know how it is,” she says of this insomniacal period of forensic legal work and breastfeeding, “you’re up anyway, so it’s either that or watching Orange Is the New Black.” The 33-year-old has a tiny diamond stud in her nose and an African head wrap that’s a little bit Nefertiti, a little bit Nina Simone. She checks her smartphone; there are just a handful of new messages. Even Transfield’s directors must only now be stirring in their beds, ruing the fact that this striking woman is coming towards them.

Narayanasamy is GetUp!’s human rights campaign director. Her No Business in Abuse (NBIA) campaign has been targeting Transfield’s investors, clients and financiers, asking them to reconsider their relationships with the company. Today may provide another chance to deliver the message: Transfield is holding its annual general meeting in Sydney, and NBIA’s representatives plan to attend.

When the taxi makes it to the airport’s drop-off area, Narayanasamy swiftly pays and rushes into the terminal. There is not enough time; it’s always slipping away, running out – most pressingly, in her mind, for people in detention who are trying to maintain their sanity. She starts to jog just to make it to the gate. “I haven’t run this much since before the caesarean,” she pants.

Outside the Sydney Mint, a few hours later, members of the riot squad stiffly commingle with protesters, who range from a band of polite retirees volunteering for GetUp! to more seasoned agitators aligned with other groups. Narayanasamy holds a megaphone that looks oversize next to her petite frame. She’s been involved in refugee politics for 15 years. Reminders of her hardcore activist past are close by, marking her evolution into someone “who prioritises being able to read a spreadsheet”.

“This company is doing business in abuse,” she announces plainly. “It’s paid $1.4 million a day to do business in abuse. That the government pays you to do it doesn’t make it right. And we want this company to know today they need to face the consequences!”

“Shame!” call protesters as a handful of investors sidle through the wrought-iron gates.

“Shame!”

Should a company that is trying to downplay its mammonist credentials have chosen a venue other than the Mint’s old coining factory? Inside ‘The Gold Melting Room’, with its charcoal walls and shuttered windows, the mood is funereal. Rows of Transfield’s lawyers, public relations advisers and security staff uniformly wear dark suits and talk in hushed tones. One can’t make out the chant of the protesters outside, only the rise and fall of loathing.

An associate of NBIA bought the minimum number of Transfield shares needed to vote, and has sent two proxies to the meeting to question the directors. Brynn O’Brien, NBIA’s business and human-rights technical adviser, is dressed in “’80s corporate glam”: a black tailored jumpsuit, red Hermès-esque scarf and gold-tone jewellery. (At the last minute, she completed the outfit by swapping scuffed sandals for nude-coloured pumps.) She’s accompanying Mohammad Ali Baqiri, a former child detainee on Nauru.

Transfield’s chairman, as she’s known, is Diane Smith-Gander, a tall, aquiline-featured woman with a helmet of steel-blonde hair. She opens the meeting, and two protesters stand and shower her in curses. Security guards swiftly show them to the door.

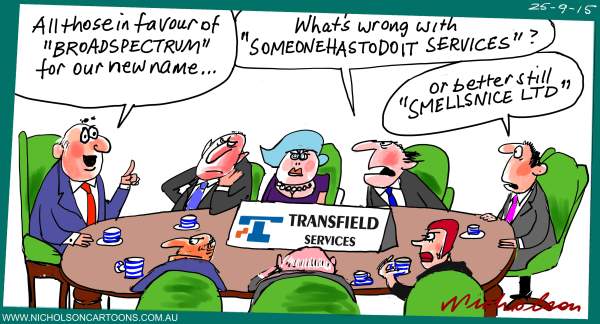

Those remaining hear about Transfield’s “solid progress in financial metrics”; the CEO’s cash and stock options; the board’s compensation; and their decision to rebrand from Transfield to the “exciting new name” of Broadspectrum. (No mention is made of the fact that the company’s founding family withdrew permission for Transfield to use the name, so as to distance themselves from the detention centres.) Then there’s news about the Environmental Management System, the Equality and Diversity in the Workplace Policy, and the Community Engagement Approach. Meanwhile, a security guard with an earpiece roams the room, threatening to evict anyone recording the details … Any questions?

Handsome, with full lips and a pompadour, Baqiri has spent $150 to look businesslike: blue suit, white shirt and a new pair of shoes. He’s in his last semester of a law degree and is carrying around notes for an exam tomorrow.

In the dimly lit room, he takes the microphone and introduces himself: “My name is Mohammad Ali Baqiri, but in Nauru detention centre I was known as a number and I was 3283. I’m an Afghan Hazara. I fled the Taliban to seek protection in Australia at the age of ten, without my parents but with my brother’s family. I spent three years of my life in Nauru detention centre from 2001. In 2001 or 2015 it’s always the same. When you hold people like me indefinitely on a remote prison island, they suffer.”

NBIA’s report offers evidence of that. Narayanasamy and her co-authors have been scrupulous about only including information from previous government, Amnesty International or United Nations inquiries, but unfortunately that still gives them plenty of material on sexual and physical assaults; phenomenal levels of depression and anxiety; third-world obstetric and paediatric care; inadequate hygiene facilities; unbearable heat with poor or non-existent shaded, safe, vermin-free places for children to play; a mentality of suspicion among staff members towards the refugees; the dehumanising practice of being referred to as a number; and children engaging in self-harm, including lip-stitching, swallowing detergent and self-laceration. The report quotes Peter Young, the former chief psychiatrist for Australia’s detention network, speaking in August 2014. “If we take the definition of torture to be the deliberate harming of people in order to coerce them into a desired outcome, I think it does fulfil that definition.”

“As an Australian citizen,” Baqiri continues, “I’m ashamed at what these vulnerable people have to go through to then be tortured in a detention centre …”

Smith-Gander tries to cut him off, but as the board members sit on an elevated platform, impassive as judges, he goes on.

“I’d like to leave you with these questions. Is it OK for this company to profit from the abuse of vulnerable men, women and children in mandatory detention centres? And my second question is, do you think reputable organisations like hospitals, and universities, and indeed other companies will continue to do business with this company if it continues to do business in abuse? Thank you.”

You have to hand it to Smith-Gander: the woman’s a pro. First, she thanks Baqiri and says Transfield is very glad he could join them to express his views. She apologises for interrupting him – she wanted to be sure he had a question – and thanks him for the way he handled it. But there’s a little of the headmistress in her: Baqiri could be Nauru’s valedictorian of the year.

“Obviously you have experienced a number of challenges,” she offers, “and I’m very genuine in saying you have our respect and you must have a huge amount of strength to have overcome those challenges to be the person you are today. You are a fantastic role model for young people in this country and I’m personally glad you’re an Australian citizen …”

She says she hopes it’s clear from the company’s statements that they do respect all asylum seekers and they do have zero tolerance for abuse. “But many of your arguments are political arguments and …” Smith-Gander pauses, set to deliver a line in which she’s found safety before. She lingers on each word: “We do not see politics as our business.”

And this may prove a very grave myopia.

“Do you have a pen?” Narayanasamy asks. It’s after the meeting, in a cafe around the corner. “I’ll draw something for you.” With a series of circles on a page, she maps Transfield’s investor picture, particularly the super funds, the fund managers and the “mum and dad” shareholders. She connects these together and one gets a glimpse of her determination. Then she moves on to financiers. “Banks hold almost $400 million in syndicated loans with Transfield, which expire in 2017.”

Narayanasamy’s diagram grows weblike. “OK, who are their clients?” she asks rhetorically. In a way, she’s re-enacting her gotcha moment, because she realised she had a viable campaign when she started investigating Transfield’s maze of services. “They contract with schools, with universities, with councils and public transport. They run the ferries.” As she went on to write in NBIA’s report, “The network of money that keeps abuse in business is large – but we’re at the centre of it.”

“Then,” she continues, “we asked, ‘All right, what is Transfield’s corporate reputation?’ We assessed their directors. They all have links across small-l liberal institutions.” One of them is a board member of the Australian National Committee for UN Women; another is a director of the Black Dog Institute, an NGO dealing with the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of mood disorders. “‘All right,’ we thought, ‘who are the audiences these people respond to?’ You’ve got academics, philanthropists, medical professionals, and once we mapped all that we knew we were sitting on a winnable campaign.”

Polls show 25% of Australians share Narayanasamy’s fervent opposition to offshore detention: many are high net worth and highly educated. Her target audience. “That’s who we need to talk to. They’re our people.”

Fifteen years ago, as a Monash University law student, Narayanasamy started visiting Baxter and Woomera detention centres, another well-meaning young activist. “One of the first things I realised was that there were just a whole lot of young men who were terribly lonely, and terribly at sea, and actually they needed to see our parents.” Hers are Tamils. “The minute my mum walked in that door, people fell on her, actually fell on her, and touched her feet, and wanted her to cook for them, to feed them. It’s a real cultural thing that your mum feeds you.”

Narayanasamy’s family informally adopted a young Tamil refugee they met; he moved in with them after his four years in detention came to an end. “There was a big group of guys,” she says, remembering the detainees who were all eventually granted asylum. “Heaps of them are irretrievably broken. It’s such a waste.”

After university, she joined a corporate law firm, before, a year later, taking the skills she’d learnt to her dream job as an economic justice advocate for Oxfam. In her free time, Narayanasamy would also meet with a loose collective of refugee activists. They’d explored the idea of a campaign like this for a while, but with her research in hand suddenly they could see the opportunities to affect Transfield and its network’s cost–benefit analysis. Would it be possible to make companies think twice not just about the moral and ethical components of their business but also the financial and legal implications?

For most of the year, Narayanasamy has been meeting with various banks and other corporate stakeholders. Initially she took her children to meetings, placating her three-year-old daughter with an iPad, while, in one instance, her infant son vomited on a CEO’s shoes. Despite this, she claims, “The level of support inside the corporate world is really high. They don’t support what we’re doing necessarily, but they think the detention centres are a waste of money and human potential.” Undoubtedly their lawyers are also investigating NBIA’s claim that “all companies, including Transfield, have an overarching responsibility to respect human rights in their business activities. A responsibility clearly outlined by the authoritative global standard – the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and echoed in a host of other international and domestic standards.”

Earlier in 2015, Transfield’s share price started sliding. Narayanasamy refuses to quantify the effect of her campaign on the share price. (“The last thing some super fund needs is some fucking activist taking credit for their decision.”) How would she know, she argues, who is selling what or why? But in August the health services super fund HESTA announced it was divesting its 3.5% stake in Transfield, and the company’s largest shareholder, the funds management firm Allan Gray, has also stated it is reviewing its holdings.

The newly named Broadspectrum is on the verge of signing another five-year contract with the Australian government. “The government can and will throw more money at detention centres. What we can do is force them to do it in the context of a massive campaign in which businesses, institutions and individuals have signed the No Business in Abuse pledge.”

She stands up. Her phone’s bleating is constant and she’s late for another meeting. Plus Transfield’s lawyers have started writing. There are investors she should visit and GetUp! supporters to keep updated. Narayanasamy is on the last flight home, and soon after walking in the door at midnight she’ll realise she has a case of gastro thanks to the children, and soon after that they will be up again, and the campaign’s momentum – as if charged by her intensity – will continue unabated. But now, her energy unflagging, she walks down Pitt Street with a kind of restless calm, already hypothesising about the alternatives to detention, testing out her latest set of plans.

Burning the stakeholders: Shen Narayanasamy takes on Transfield

- By John Richardson at 11 Jan 2016 - 1:06pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

11 min 7 sec ago

1 hour 46 min ago

1 hour 54 min ago

4 hours 11 min ago

5 hours 19 min ago

15 hours 35 min ago

19 hours 55 min ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 3 hours ago

1 day 4 hours ago