Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

would you kill the fat man .....

At 4:13 in the morning on June 13, 1944, there was an explosion in a lettuce patch 25 miles southeast of London.

Britain had been at war for five years, but this marked the beginning of a new torment for the inhabitants of the capital, one that would last several months and cost thousands of lives. The Germans called their flying bomb Vergeltungswaffe - retaliation weapon. The first V1 merely destroyed edible plants, but there were nine other missiles of vengeance that night, and they had more deadly effect.

The V1s were a terrifying sight. The two tons of steel hurtled through the sky, with a flaming orange-red tail. But it was the sound that most deeply imprinted itself on witnesses. The rockets would buzz like a deranged bee and then go eerily quiet.

Silence signaled that they had run out of fuel and were falling. On contact with the ground they would cause a deafening explosion that could flatten several buildings. Londoners tempered their fear by giving the bombs a name of childlike innocence: doodlebugs. (The Germans called them “hell hounds” or “fire dragons.”)

Because the missiles were not piloted, they could be dispatched across the Channel day or night, rain or shine. That they were unmanned made them more, not less, menacing. The doodlebugs were aimed at the heart of the capital, which was both densely populated and contained the institutions of government and power. Some doodlebugs reached the targeted zone. One smashed windows in Buckingham Palace and damaged George VI’s tennis court. More seriously, on June 18, 1944, a V1 landed on the Guards Chapel, near the Palace, in the midst of a morning service attended by both civilians and soldiers: 121 people were killed.

The skylight of nearby Number 5, Seaforth Place, would have been shaken by this explosion too. Number 5 was an attic flat overrun by mice and volumes of poetry. There was a crack in the roof, through which could be heard the intermittent growl of planes, and there were cracks in the floor as well, through which could be heard the near constant roar of the underground. The flat was home to two young women. Iris was working in the Treasury, and secretly feeding information back to the Communist Party; Philippa was researching how American money could revitalize European economies once the war was over. Both Iris Murdoch and Philippa Bonsanquet would go on to become outstanding philosophers, though Iris would always be better known as a novelist.

Iris’s biographer, Peter Conradi, says the women became used to walking to work in the morning to discover various buildings had disappeared during the night. Back at the flat, during intense bombing raids, they would climb into the bathtub under the stairs for comfort and protection.

They weren’t aware of it at the time, but matters could have been worse. The Nazis faced two problems. First, despite the near miss to Buckingham Palace, and the terrible toll at the Guards Chapel, most of the V1 bombs actually fell a few miles south of the center of London. Second, this was a fact of which the Nazis were ignorant.

An ingenious plan presented itself in Whitehall. If the Germans could be deceived into believing that the doodlebugs were hitting their mark - or, better still, missing their mark by falling north - then they would not readjust the trajectory of the bombs, and perhaps even alter it so that they fell still farther south. That could save lives.

The details of this deception were intricately plotted by the secret service and involved several double agents, including two of the most colorful, ZigZag3 and Garbo. Both ZigZag and Garbo were on the Nazi payroll but working for the Allies. The Nazis requested eyewitness information about where the bombs were exploding - and for a month they swallowed up the regular and misleading information that ZigZag and Garbo provided.

The military immediately recognized the benefits of this ruse and supported the operation. But for the politicians it had been a tougher call. There was an impassioned debate between the minister for Home Security, Herbert Morrison, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. It would be too crude to characterize it as a class conflict, but Morrison, who was the son of a policeman from south London and who represented a desperately poor constituency in east London, perhaps felt more keenly than did Churchill the burden that the operation would impose on the working-class areas south of the center. And he was uneasy at the thought of “playing God,” of politicians determining who was to live and who to die. Churchill, as usual, prevailed.

The success of the operation is contested by historians. The British intelligence agency, MI5, destroyed the false reports dispatched by Garbo and ZigZag, recognizing that, were they ever to come to light, the residents of south London might not take kindly to being used in this way. However, the Nazis never improved their aim.

By the end of August 1944, the danger from V1s had receded. The British got better at shooting down the doodlebugs from both air and ground. More important, the V1 launching pads in Northern France were overrun by the advancing Allied forces. On September 7, 1944, the British government announced that the war against the flying bomb was over. The V1s had killed around six thousand people. Areas of south London - Croydon, Penge, Beckenham, Dulwich, Streatham, and Lewisham - had been rocked and pounded: 57,000 houses had been damaged in Croydon alone.

Nonetheless, it’s possible that without the double-agent subterfuge, many more buildings would have been destroyed - and many more lives lost. Churchill probably didn’t lose too much sleep over the decision. He faced excruciating moral dilemmas on an almost daily basis. But this one is significant for capturing the structure of a famous philosophical puzzle, eventually posed by Philippa Foot (née Bosanquet) after the war - the trolley problem:

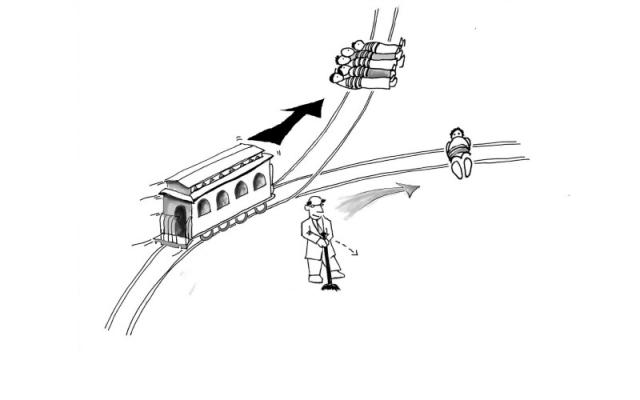

A runaway trolley is hurtling down the track. Its brakes have failed. Ahead, five people are tied to the rails. You are standing on the side of the track. By turning a switch you can divert the trolley down a side track. That will save five lives. Unfortunately, one man is on this side track, and he would be killed. What should you do?

Many studies have shown that almost everybody - young and old, rich and poor, men and women - think it’s right to divert the trolley. Churchill would no doubt agree. But this contrasts with another case, posed by another philosopher.

You’re on a footbridge overlooking the railway track. You see the trolley hurtling down the track and, ahead of it, five people tied to the rails. Can these five be saved? Again, the moral philosopher has cunningly arranged matters so that they can be. There’s a very fat man leaning over the railing. If you were to push him over the footbridge, he would tumble down and smash on to the track below. He’s so obese that his bulk would bring the trolley to a shuddering halt. Sadly, the process would kill the fat man. But it would save the other five. Should you push the fat man?

In this scenario, very few people believe you should push the fat man. That’s odd. For in both scenarios, there’s a choice between killing one and saving five. These thought experiments are designed to test our moral intuitions, to help us develop moral principles and thus to be of some practical use in a world in which real choices have to be made, and real people get hurt. There is a reason why this puzzle has never been fully solved, philosophically: it is complicated . . . really complicated.

Questions that, at first glance, appear straightforward - such as “When you pushed the fat man, did you intend to kill him?” - turn out to be multidimensional.

For the past half century, trolleyology (as this sub-genre of philosophy has jokingly been called) has provided a vehicle to contest fundamental issues in ethics - vital questions about how we should treat others and live our lives. When Foot introduced the trolley problem it was to intervene in the debate over abortion. Nowadays, a trolley-like challenge is more likely to arise in deliberations about the legitimacy of types of conduct in warfare. Churchill’s dilemma - about whether to attempt to redirect rockets to less populous areas - continues to be reincarnated in a variety of other forms too. The Fat Man quandary highlights the stark clash between deontological and utilitarian ethics. Most people do not have utilitarian instincts. They believe that Winston Churchill would have been wrong to use citizens as a human shield, even if his objective was to save the lives of others. He would have been equally wrong to force or inveigle people into the path of a Nazi threat, even if in order to save lives. But, on balance, he was surely right to support the deception plot to redirect the doodlebugs toward south London.

Why the difference? Philosophers still can’t agree. But whatever the answer, the strange situation of the fat man on the footbridge must hold the key. I wouldn’t kill the fat man. Would you?

- By John Richardson at 2 Jan 2014 - 10:03am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

2 hours 22 min ago

2 hours 48 min ago

4 hours 44 min ago

10 hours 40 min ago

12 hours 3 min ago

12 hours 11 min ago

22 hours 16 min ago

23 hours 29 sec ago

23 hours 19 min ago

23 hours 27 min ago