Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

pedalling to perdition ....

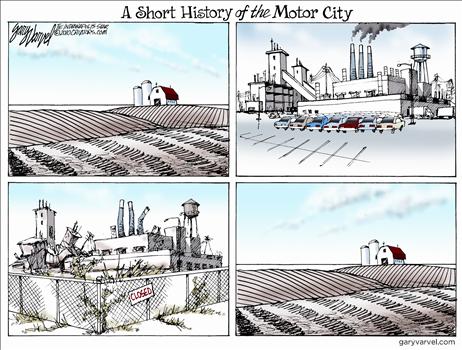

Australians might view Detroit's decline with only passing curiosity but it offers an object lesson in the need to nurture economic competitiveness, writes Julie Novak.

The announcement that the city of Detroit, the heartland of modern American manufacturing, has filed for bankruptcy is an event seemingly lifted out of an Ayn Rand novel.

Originally published in 1957, Ayn Rand’s greatest work, Atlas Shrugged, portrayed a dystopian world in which economic activity was collapsing under the weight of government interventions and anti‑capitalistic social sentiments.

The mass 'capital strike' devastated many communities, and perhaps none more than the small, mid‑western American town of Starnesville, originally established by entrepreneur 'Jed' Starnes to house up to 6,000 workers at his motor vehicle manufacturing plant.

The collapse of Starnes' Twentieth Century Motor Company, expedited by a disastrous collective bargaining agreement in which workers worked according to their ability but were paid according to their need, soon led to the decline of the town and a precarious existence for its remaining inhabitants:

"A few houses still stood with the skeleton of what had once been an industrial town.

Everything that could move, had moved away; but some human beings had remained. The empty structures were vertical rubble; they had been eaten, not by time, but by men: boards torn out at random, missing patches of roofs, holes left in gutted cellars."

That some of Detroit's precincts, strewn with abandoned apartment blocks and shuttered factories and small business outlets, offers a real‑world analogue for the fictionally downtrodden Starnesville has http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/danielhannan/100227375/obamanomics-is-...)" target="_blank">not gone without notice.

An important point to draw from Atlas Shrugged is that entrepreneurs and suppliers didn't 'shrug' off the excesses of government taxes and regulations, and contend with the social animosities towards market conduct, by abstaining from productive activities altogether.

Rather, the productive 'shrugged' by moving to places more hospitable to economic creativity and wealth generation, most notably the secluded, but welcoming, haven of 'Galt's Gulch'.

It is here that Rand's fiction, again, contains a grain of truth of what has transpired for Detroit.

In recent decades, entrepreneurs and business owners fled high-cost Detroit in favour of other American locations, notably low-taxing, 'right‑to‑work' jurisdictions such as Texas, or to other countries altogether, taking their prized capital and knowledge with them.

Aspirant workers, and others looking for a better life for themselves and their families, had also left Detroit, once America's fourth largest city, in droves, with the city's total population falling from 1.9 million people in the 1950s to a little over 700,000 today.

A long term process of de-population of this magnitude inevitably spells trouble, through fewer local economic interactions to sustain a vibrant market economy, and a smaller revenue base with which to provide core government services.

One culprit underlying Detroit's problems, that should have been avoided, have been the anti-competitive activities of the union movement, as represented in both the private and public sectors, in efforts to secure wages and conditions at odds with the objectives of providing efficient commodities and public services.

Under pattern bargaining arrangements enforced upon General Motors, Ford and Chrysler over many years, the United Auto Workers union had succeeded to secure lavish benefits for their members.

Prior to the unconscionable auto bailouts of 2008, automotive workers in Detroit enjoyed $70 per hour in wages and benefits, seven weeks of paid vacation, and generous pensions after 30 years of employment.

These elevated costs of employment contributed to the production of expensive local American vehicles, which were increasingly superseded in the market by cheaper, and resultantly more popular, imports.

The union strategy of treating companies as cash cows for their members could not be economically sustained in such an environment, which has been compounded in recent years by sluggish economic conditions within the United States.

Aggressive public sector union demands over a long period led to a regime of exorbitant pensions and other benefits for municipal government workers, typically far exceeding those enjoyed by most private sector workers.

It is estimated that about $9.2 billion, or half of the total debts owed by the City of Detroit, are represented by pension and health benefits, with the bulk of the remaining debts owed to municipal bondholders.

In a scenario whereby the public sector worker becomes master as opposed to servant, it is unsurprising that basic services would suffer to the detriment of the needs of local communities.

For example, the average police response time to a call-out is just under an hour in Detroit, while two-thirds of ambulance services remain idle.

Whilst many Australians will probably view Detroit's woes with a sense of passing curiosity at best, the troubles besetting the city should, rather, serve as an object lesson regarding the need to ensure economic competitiveness as comprehensively as possible.

Demands for better wages and employment conditions by unions should be grounded on solid evidence of improved workplace productivity, and have due consideration to the overall economic environment faced by firms.

For their part, governments should lay out a 'welcome mat' of low taxation, streamlined regulations, and efficient spending to enterprising all-comers from around the world, and without the need to resort to 'corporate welfare' subsidies or other specific assistance.

To safeguard our prosperity, Australia should be economically mindful of doing everything that Detroit hasn't managed to do.

- By John Richardson at 25 Jul 2013 - 7:03am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

6 min 32 sec ago

4 hours 25 min ago

9 hours 47 min ago

11 hours 41 min ago

13 hours 10 min ago

15 hours 4 min ago

15 hours 51 min ago

1 day 7 hours ago

1 day 7 hours ago

1 day 8 hours ago