Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

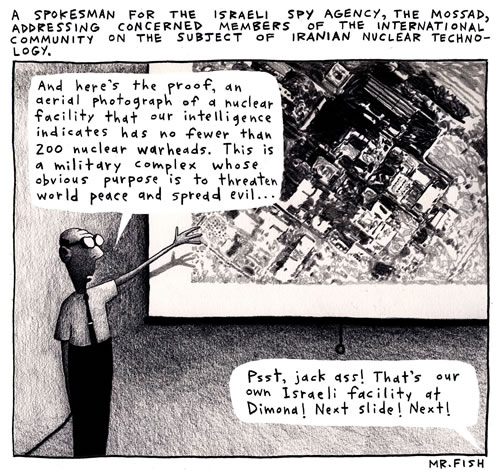

avoiding peace at all costs ....

doubtless another issue that bob will be keen to pursue at the UN security council …..

On September 19, to nobody’s surprise, Shaul Chorev, the director-general of Israel’s Atomic Energy Commission, announced that his government would not attend an upcoming conference devoted to establishing a nuclear-free Middle East. The announcement reaffirmed Israel’s long-standing position that a nuclear-free zone can come about only as a consequence of a lasting regional peace. Until such a peace is achieved, Jerusalem will not take any tangible steps toward eliminating its nuclear weapons.

At least on the face of it, this stand is sensible. For 45 years, Israel has been the only nuclear power in the Middle East, enjoying a formidable strategic safety net against any existential threat. Since 1957, Israel has invested tremendous resources in building up a solid nuclear arsenal in Dimona. Today, according to various estimates, this stockpile comprises some 100–300 devices, including two-stage thermonuclear warheads and a variety of delivery systems, the most important of which are modern German-built submarines, which constitute the backbone of Israel’s second-strike capability. For Israel to give up these assets in the midst of an ongoing conflict strikes most Israelis as irrational.

This consensus, however, overlooks the fact that Israel’s nuclear capability has not played an important role in the country’s defense. Unlike other nuclear-armed states, Israel initiated its nuclear project not because of an opponent’s real or imagined nuclear capability but because of the worry that, in the long run, Arab conventional forces would outstrip the power of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). As early as the 1950s, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion sought to manage the threat of modernizing Arab armies, which were inspired by pan-Arab sentiment and backed by the Soviet Union, by developing the ultimate deterrent. Shimon Peres, the architect of Israel’s nuclear program and now Israel’s president, relentlessly argued in public speeches and writings that Israel needed to compensate for the large size of the Arab armies with “science” - a code word for nuclear arms.

As it turned out, however, Arab conventional superiority never materialized. Ever since Israel crossed the nuclear threshold on the eve of the 1967 war, the qualitative gap between Israel’s conventional forces and those of its Arab neighbors has only grown. Today, particularly as the Syrian army slowly disintegrates, the IDF could decisively rout any combination of Arab (and Iranian) conventional forces. This advantage, combined with the United States’ support for Israel, is what has kept Arab countries from taking up arms against the Jewish state - not the fear of nuclear retaliation.

If, of course, Iran were to obtain a nuclear weapon, the arsenal at Dimona would no longer be irrelevant; it would be an important hedge against Iran. But far from being a secure balance, as the international relations theorist Kenneth Waltz has argued, this state of affairs would be highly unstable, especially at first. The two states deeply distrust one another and lack any effective channels of communications. Since Iran would not have a second-strike capability and the Israelis often prefer preemption in conflicts, Jerusalem might be tempted to launch a nuclear first strike. Moreover, other nearby countries, such as Saudi Arabia, might themselves seek nuclear weapons, further destabilizing the region and raising the possibility of an unintentional nuclear exchange.

Fearing the prospect of living in the shadow of such terror, many Israeli officials have openly called for a military strike to halt Iran’s nuclear program. They are spurred by anxieties that are deeply rooted in Israeli culture, stemming from the trauma of the Holocaust and of two thousand years of perceived and real victimhood throughout the Jewish Diaspora. Israeli leaders, particularly Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, now evince a belief that the country can rely only on itself when it comes to ensuring its security and its existence.

The problem for Israel, however, is that a strike on Iran might carry grave consequences, especially since the IDF cannot completely destroy Iran’s nuclear infrastructure on its own. Israel can delay Iran’s nuclearization, but it cannot prevent it. Meanwhile, a military strike could provoke a great backlash, including missile and rocket attacks by Iran, Hezbollah, and Hamas on Israeli population centers. Just as worrisome, a strike would provide the Iranian regime with a handy justification for its decision to go nuclear.

And so Israel finds itself in a strategic dilemma: it considers an Iranian bomb an existential threat, but it cannot stop Iran’s nuclearization by itself or without provoking an unpredictable backlash.

Fortunately, Israel has a way out of this strategic limbo: by agreeing to give up its nuclear arsenal. Instead of rejecting the calls for a region free of weapons of mass destruction, Jerusalem could participate in such an initiative - joining in a similar sacrifice by all other regional actors, including Iran. The conventional wisdom is that this would be a bad bargain for Israel, giving up too much in exchange for too little. But such a bold move could set in motion a long-term process that might end the bitter stalemate over Iran’s nuclear program. Iran has been calling for a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the Middle East since 1974 and perceives the Israeli arsenal as a great threat, so it will have no choice but to support the initiative. And purely from a security perspective, Israel would be safer in a WMD-free region. It would maintain its conventional superiority and its ability to deter conventional challenges - all the while eliminating the prospect of nonconventional threats, such as an Iranian nuclear bomb or Syrian chemical weapons.

Of course, Israel is not likely to actually abandon its own nuclear arsenal anytime soon, and, even if it did, it would not lose the know-how and the capability to produce nuclear arms in the future. But a change in policy that started Israel in this direction would at the very least increase the pressure on Iran to give up its own nuclear project.

Several developments might eventually encourage Jerusalem to take the plunge. As Iran inches its way to a bomb, the status quo of the last 45 years, during which Israel succeeded in maintaining its regional nuclear monopoly with hardly any external pressures, is becoming increasingly untenable. If Israel does ultimately resort to the unilateral use of military force against Iran, international pressure will build for Israel to give up its strategy of nuclear opacity, to come clean about its own arsenal, and to take tangible steps toward establishing a nuclear-free Middle East. After all, the logic of using force to secure a nuclear monopoly flies in the face of international norms. The same pressure might come about if the international sanctions against Iran prove to be successful and Tehran agrees to limit the country’s nuclear development, or if an American-led coalition destroys Iran’s nuclear facilities. Moving toward a nuclear-free Middle East may be the price that Jerusalem will be asked to pay for the efforts taken by the international community to bail Israel out of a threatening situation. On the other hand, if Iran does become a nuclear state, Israeli voters may pressure their government to give up the country’s nuclear weapons in exchange for Iran doing the same. According to a 2011 survey conducted by Shibley Telhami of the University of Maryland, 65 percent of Israeli Jews prefer that neither Iran nor Israel have nuclear weapons.

Israel’s nuclear capability has never been essential for the defense of the country, and it would become important only if Iran were to get its own nuclear weapon. But that dangerous outcome, especially for a one-bomb state like Israel, need not materialize. If Israel commits to a Middle East free of weapons of mass destruction, offering up its own nuclear capability as a bargaining chip, it may finally make good use of its most controversial strategic asset.

- By John Richardson at 28 Oct 2012 - 7:57am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 40 min ago

3 hours 33 min ago

4 hours 36 min ago

5 hours 8 min ago

5 hours 45 min ago

6 hours 11 min ago

6 hours 21 min ago

7 hours 32 min ago

9 hours 54 min ago

19 hours 40 min ago