Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

in the public interest .....

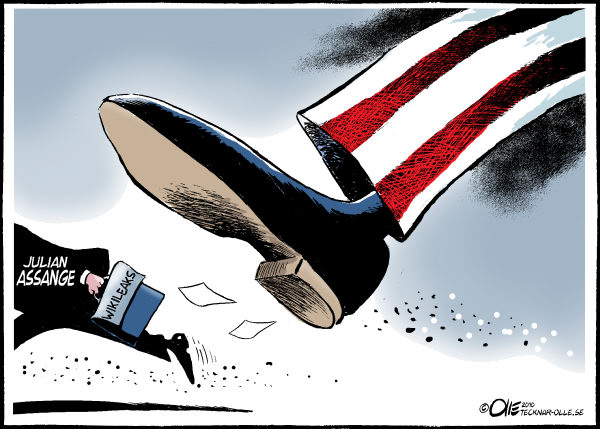

In their attacks on WikiLeaks and its founder Julian Assange, traditional news organisations seem to have forgotten that his objectives are the same as theirs.

When a fellow MP once observed to Ernest Bevin, foreign secretary in the postwar Labour government, that his cabinet colleague Herbert Morrison was "his own worst enemy", Bevin - who loathed Morrison - famously replied: "Not while I'm alive, he ain't." I keep thinking of this every time Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, appears in the news. The man does indeed appear to be his own worst enemy - alienating all but the most sycophantic supporters, repudiating his "authorised" biography, and so on. The impression one gets from conversations with people who have worked with him is that, as a colleague, he makes the late Steve Jobs look like St Francis of Assisi. But the truth is that Assange has far more formidable enemies than himself. And many of them work for what we might now call "old media".

This was particularly evident when the "Cablegate" controversy erupted a year ago. The US government, impaled on its own windy rhetoric about the importance of a free and open internet as a scourge of authoritarian regimes, suddenly found itself on the sharp end of a spot of networked journalism. And it responded by launching a ferocious attack on WikiLeaks which has been subsequently dissected by the Harvard legal scholar Yochai Benkler.

In his paper Prof Benkler chronicles how the US government vastly overstated the extent of the actual threat of WikiLeaks. But, more significantly, he also shows the extent to which mainstream US media connived in this enterprise. He analysed all the news stories at the time of the embassy cables release and found that in the first fortnight of the controversy about two-thirds of news reports in the US explicitly misstated what WikiLeaks had released - claiming that hundreds of thousands of cables had been "dumped" online at a time when only a few hundred cables had been released, in redacted form, and only after they had already been published by one or more of the traditional newspaper partners in the endeavour (the Guardian, the New York Times, El País and Der Spiegel).

"The pattern of misreporting in the news media," Benkler maintains, "fit the pattern of overstatement by government actors, both administration officials and senators. It fed into a description of WikiLeaks as though it was some terrorist organisation as opposed to what it is, which is, in fact, a journalistic enterprise." The US vice-president Joe Biden described Julian Assange as "like a hi-tech terrorist" - a phrase that Benkler characterises as capturing "the overstated, overheated, irresponsible nature of the public and political response to what was fundamentally a moment of journalistic disclosure".

The most depressing thing about old media's treatment of the controversy was its implicit denial that, in the end, WikiLeaks and traditional news organisations are in the same business - namely publishing, in the public interest, information that powerful agencies in society wish to keep secret. The idea that WikiLeaks might be entitled to the same first amendment protection that US news organisations enjoy doesn't seem to have occurred to many of the print journalists who gleefully traduced the website and its erratic founder.

And yet, as Benkler puts it, if Bradley Manning (the whistleblower who allegedly supplied WikiLeaks with the confidential information) "had walked off a military base in Oklahoma and handed the disc with the files to the editor of a tiny local newspaper of a small town 100 miles away, we would not conceivably have treated that local newspaper as categorically different from the New York Times. Indeed, we lionise the local newspaperman as a bulwark against local corruption".

Quite. By conniving in the "framing" of WikiLeaks as a terrorist organisation, old media were implicitly rendering it ineligible for constitutional protection. And, worse, - this also enabled them to overlook what amounts to legalised torture of Private Manning by the US authorities.

The strangest thing of all is that the New York Times - which, remember, was a partner in the release of the redacted diplomatic cables - has been perhaps the sharpest old media critic of WikiLeaks. Last week its esteemed media columnist, David Carr, returned to the fray with a piece about WikiLeaks's current financial and other problems and asking "Is this the WikiEnd?" And yet Carr's employer is the same newspaper that released the Pentagon papers in 1971 - and went all the way to the supreme court to defend its right to do so. I can't see much difference between what WikiLeaks did with the cables and the New York Times did with the Pentagon papers. The lesson for old and new media alike is simple: from now on, we're all in this together.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2011/nov/13/assange-wikileaks-misreporting-old-media

- By John Richardson at 14 Nov 2011 - 1:10pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

6 hours 44 min ago

7 hours 58 min ago

8 hours 55 min ago

11 hours 2 min ago

11 hours 45 min ago

13 hours 16 min ago

13 hours 35 min ago

15 hours 15 min ago

16 hours 14 min ago

16 hours 18 min ago