Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

in the absence of principles .....

The allegations are horrifying, the evidence credible: massed civilians shelled and bombed, enemy leaders shot down after surrendering, naked and bound male and female prisoners executed by jeering soldiers. All happening just over two years ago in a nearby Commonwealth country.

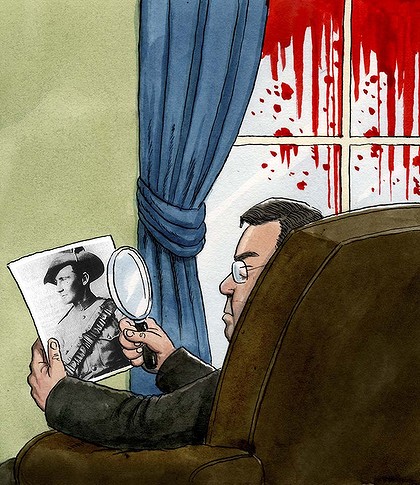

Straight after this was dumped on Canberra's doorstep, our top law official moved into action on war crimes. The federal Attorney-General, Robert McClelland, announced he would ask the British government to review the fairness of the military trial of Harry ''Breaker'' Morant and other Australians convicted of shooting prisoners and a German missionary during the Boer War - a partial surrender to a sentimental lobby which believes orders or nods and winks from above somehow excuse their crimes.

This intervention in a 110-year-old case stands in deep contrast to Canberra's reluctance to address present-era war crimes and unfair trials. It's ''unbelievable'' to Ben Saul, a Sydney University professor in international law. ''Given what he hasn't done, about [David] Hicks, a guy who is still alive and didn't kill 11 or 12 people in cold blood, and got a manifestly worse trial than Breaker Morant got, it's pretty ordinary stuff.''

The contrast became even more bizarre when the head of government accused of ultimate responsibility for the contemporary war crimes, the Sri Lankan President, Mahinda Rajapaksa, landed in Perth a few days later to attend this week's Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting.

Rajapaksa's sweeping victory in 2009 over the Tamil Tiger separatists involved a deliberate government strategy of keeping out and targeting independent witnesses. Since the conflict, refugees have arrived to give first-hand testimony to an inquiry launched by the International Commission of Jurists local chapter, headed by former NSW Liberals leader and Supreme Court judge John Dowd.

Its findings of credible evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity by the Sri Lankan government were handed to the Australian Federal Police last week, backing up earlier conclusions by a UN Expert Panel. (Neither exonerate the Tigers from similar serious charges - but their leaders are all dead).

On top of that, an Australian engineer of Sri Lankan Tamil background, Arunachalam Jegatheeswaran, launched a private prosecution on Monday in the Melbourne Magistrates Court against Rajapaksa for war crimes he says he witnessed as a volunteer relief worker in the conflict zone.

McClelland promptly quashed the case, claiming it breached domestic law and Australia's treaty pledges of diplomatic and sovereign immunity for visiting leaders. A smokescreen, of course, since domestic law does allow private war crimes prosecutions - if they are taken over by federal prosecutors and approved by the attorney-general. As for immunity, Australian National University expert Donald Rothwell says this is yet to be tested in an Australian court where serious war crimes are involved.

It was a political decision. The government wanted the CHOGM to be a happy event; it needs Rajapaksa's co-operation to stop Tamil boat people setting off; it is glad the Tamil Tigers have been finished off.

As tends to be the way, the strongest voice on Sri Lanka came from one of most distant countries. Canada's Stephen Harper has been threatening to boycott the 2013 CHOGM in Sri Lanka and oppose Rajapaksa's bid to host the 2018 Commonwealth Games in his Chinese-reconstructed home town Hambantota, unless he addresses the allegations seriously. Kevin Rudd, who has been strident on Libya and Syria, kept pretty quiet.

That fits a pattern of loud general talk, little specific action. It's not just Sri Lankan and other war crime victims popping up in our midst, but alleged perpetrators. Among them a former Burmese soldier, now an Australian citizen, who confessed three months ago to having executed 24 civilians; an East Timor militia figure; the Serbian warlord ''Captain'' Dragan Vasiljkovic; and a former World War II soldier in the Hungarian Army, Charles Zentai, now 89.

The way we've handled these cases suggest moral and legal confusion far wider than the Breaker Morant case. The Burma and Timor cases were not pursued. The 1975 murders in Balibo, Portuguese Timor, have been with the AFP four years after the Sydney inquest that fingered two former Indonesian soldiers as suspects. The Home Affairs and Justice Minister, Brendan O'Connor, has backed Zentai's extradition to Hungary for investigation, even though all witnesses to his alleged murder of a Jewish youth in 1944 are dead, there is no confession and no forensic evidence - a case Israel itself would not now prosecute.

Vasiljkovic now awaits his last appeal against extradition to Croatia on charges of mass rape by himself and his troops during the 1990s Balkan wars. But as Mark Ierace, a former prosecutor in the special tribunal for war crimes in the former Yugoslavia at The Hague, points out, Australia has no fallback to try the very serious allegations against this Australian citizen and resident if extradition is ruled out.

The legislation ratifying Australia's accession to the treaty establishing the International Criminal Court applies only to crimes committed after June 2002. Before that, only certain types of war crime and crimes against humanity are covered by the Geneva and other conventions, and only in the context of international armed conflicts. In recent times, such crimes have tended to occur in internal conflicts; their victims and perpetrators spread around the world.

Vasiljkovic's failed defamation case against The Australian, which involved testimony by rape victims and cross-examination by video link from Croatia, showed the feasibility of a war crime trial in Australia, says Ierace, now the senior public defender in NSW.

''The International Criminal Court is there for the big fish,'' he said. '' This is the logical next step - that each country equips itself to deal with the smaller fish that land on their shores. Without this next step, the net has big holes in it. With this step you then ensure coverage around the globe, so there's no escape from criminal responsibility.''

Rajapaksa might be too big a fish for Australia. But political backing and resources for the AFP on war crimes to tackle direct perpetrators would make it harder for leaders like him to shrug us off.

Should Australia join a push for accountability, Sri Lankans could come to thank us: they're left with reduced freedom, security and prosperity from the ''white van'' abductions and murders of government critics, and the nepotism that also came with Rajapaksa, and seem likely to stay long after victory over the Tigers.

- By John Richardson at 29 Oct 2011 - 7:55am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

4 hours 43 min ago

5 hours 36 min ago

6 hours 53 min ago

8 hours 56 min ago

9 hours 53 min ago

11 hours 3 min ago

11 hours 53 min ago

21 hours 42 min ago

21 hours 54 min ago

22 hours 1 min ago