Search

Recent comments

- google bias...

12 hours 42 min ago - other games....

12 hours 45 min ago - נקמה (revenge)....

13 hours 45 min ago - "the west won!"....

15 hours 48 min ago - wagenknecht......

16 hours 29 min ago - the game of war....

18 hours 53 min ago - three packages....

20 hours 13 min ago - russian oil.....

20 hours 20 min ago - crime against peace....

1 day 4 hours ago - why is Germany supporting the ukrainian nazis?....

1 day 5 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

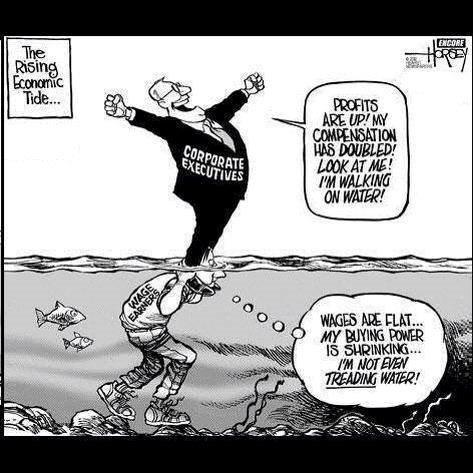

the rising tide .....

The gap between the rich and poor in Australia is growing and the most affluent are not paying enough tax, according to a survey by the Oxfam charity.

Concern about the burgeoning inequality in society has also resulted in the wealthiest Australians having too much influence, according to the report Still the Lucky Country?

The report cites a Forbes and Credit Suisse Global Wealth Databook study that found the wealthiest 1 per cent of Australians have more money than 60 per cent of the population.It found the nine richest people in Australia have a fortune that equates to the bottom 20 per cent of the country.

Of 1016 people surveyed, 79 per cent said the gap between the rich and poor had widened over the past 10 years; 76 per cent said the most affluent Australians don't pay enough tax; while 64 per cent said inequality was making Australia a worse place to live.

''Inequality threatens to further entrap poor and marginalised people and undermine efforts to tackle extreme poverty,'' the report, which will be released on Monday, says. ''By concentrating wealth and power in the hands of a few, inequality robs the poorest people of the support they need to improve their lives, and means that their voices go unheard.''

The report comes as the Greens called for a Senate inquiry into the federal government's treatment of young jobseekers, who they say face ''growing inequality'' under the government's new restrictions on welfare payments.

''The government is imposing what they call reasonable compliance requirements on young jobseekers, telling them to apply for 40 jobs a month and attend appointments with employment service providers, all while they're receiving no income support at all,'' Greens spokeswoman Senator Rachel Siewert said.

The Oxfam report is in contrast to comments made by Treasurer Joe Hockey last week as he defended the federal budget. ''I would argue the comments about inequality in Australia are largely misguided, both from a historical perspective, and from the perspective of the budget,'' he told the Sydney Institute in his speech A Budget for Opportunity.

But Oxfam Australia's chief executive Helen Szoke disagreed, saying: ''The Australia figures are quite staggering if you think that nine individuals have a net worth that is equivalent to the total 4.5 million people, or the bottom 20 cent of income workers - that's pretty stark,'' she said.

Oxfam survey finds widening gap between Australia's rich and poor

- By John Richardson at 16 Jun 2014 - 6:39pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

advance australia fair .....

Inequality is a significant, worsening and global problem. The extremes are obscene.

For example: The Oxfam data provided to the recent Davos Conference namely that the richest 85 people on the globe - who between them could squeeze into a single double-decker bus - control as much wealth as the poorest half of the global population put together (3.5 billion people).

Or the Paul Krugman example, namely that the 25 highest-paid hedge fund managers in the US - all male - earned some US$21billion in 2013, that’s more than double the wages of all the kindergarten teachers in America combined.

From World War1, until about the end of the 1970s, Australia was a relatively egalitarian society, indeed, one of the most egalitarian in the world. This egalitarianism has been eroded quite dramatically ever since.Advertisement

Our land of “the fair go” is disappearing.

As the report that I am launching today shows, the wealthiest 20 per cent of households now account for 61 per cent of total household net worth, whereas the poorest 20 per cent account for just 1 per cent of the total. In recent decades, the income share of the top 1 per cent has doubled, and the wealth share of the top 0.001 percent has tripled, and the share of the one-millionth richest (the top 0.0001 per cent) has quintupled.

Moreover, the inequality is worsening. Over the last decade, the richest 10 per cent have enjoyed almost half of the growth in incomes, and the richest 1 per cent has received 22 per cent of the gains.

At the same time, poverty is increasing, and many of those reliant on government benefits, including unemployment benefits, have fallen below the poverty line.

Most disturbingly, defining the poverty line as 50 per cent of median income suggests that some 575,000 (one child in six) were living in poverty in 2010. Some 37 per cent of those living on government benefits were living in poverty, including 52 per cent on Newstart allowance, 45 per cent of those on a parenting benefit, 42 per cent of those on a disability support pension, but only 14 per cent of those on an aged pension.

Greater inequality leads to greater stratification of the community, with adverse effects on trust, self-image, and equality of opportunity for disadvantaged groups, all of which, in turn, have negative effects on health and social stability. There is also mounting evidence that inequality impedes productivity and economic growth.

Power, money and resources are distributed unequally across our social hierarchy.

As researchers Sharon Friel and Richard Denniss have pointed out, this leads to unfairness and inequity in the immediate circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, including levels of pay and other conditions of work, access to quality health care, schools and education, social protection, the affordability of homes, and the nature of communities, cities or towns.

Clearly there are many factors at work here. The report identifies:

-globalisation in general, and the expansion of financial markets in particular

-asymmetric access to technological change

-the decline in union membership

-changes in compensation packages for top executives

-“rent seeking” behaviour, where wealthy, politically powerful and “privileged” companies, organisations and individuals use their position and resources to obtain economic gain at the expense of others without contributing to productivity.

By way of an aside, to add substance to this latter point, you could list big miners, big polluters, and even our big four banks, as examples. To expand on the Krugman example that I mentioned before, the hedge fund managers clearly don’t deliver high enough returns to justify their obscene fees, and they’re a major source of economic instability, indeed, they may represent a significant threat to the stability of the global financial system.

While our political leaders seem to wax on endlessly assuring us all that “we were created equal”, or promising “equality of opportunity”, “fairness”, “equity”, a “fair sharing of the burden of adjustment”, and the like, their policies of the last several decades have clearly compounded the problem.

Most conspicuously, tax cuts and tax expenditure concessions concentrated on the better off, especially those in superannuation, have led the way, combined with the failure to ensure that social security benefits kept pace with inflation, together with a host of other changes across many policy areas.

As the report says, to begin, there is an urgent need for a mature community debate about how inequality is impacting on our lives, our culture, our economy and our society.

The report lists nine other ways to advance Australia Fair:

1. Increase the fairness and adequacy of government revenue raising through taxation reform

2. Implement fairer funding for schools

3. Invest nationally in early childhood development, especially for disadvantaged groups

4. Set all pensions and benefits no lower that the poverty line and index them to average wages

5. Establish more job creation programs in priority areas

6. Develop new models of employee management and cooperative ownership of business

7. Implement the World Health Organisation recommendations on social determinants of health

8. Encourage an inquiry by the Productivity Commission into the impact of inequality on economic efficiency and growth, and

9. Establish a national research program to monitor progress and test the impact of interventions aimed at reducing inequality

I might add another by suggesting that an inequality impact statement be an essential attachment for all major policy proposals to Cabinet.

However, we need to ask ourselves whether there is sufficient and widespread dissatisfaction with the status quo for significant, if not radical change, in distribution?

There is obviously a growing electoral awareness of the issue, and a growing constituency for change. The reaction to the recent Budget makes the point.

Even though the Abbott government was at pains to argue that “fixing the Budget” would be done by sharing the burden of adjustment, the electoral backlash was driven by the obvious inequity of the Budget measures proposed.

The Budget proposed a cut of some 12-15 per cent in the disposable income of key lower income groups, but less than 1 per cent for those on higher incomes.

Moreover, the government burnt much of its political capital for little gain in terms of “fixing the Budget”, especially when the unfunded challenges of meeting spending commitments still persist in the out years.

However, it is possible to achieve the desired changes in a more equitable way.

Consider some examples. Better targeting of the aged pension by means of reformed asset and income tests would have been more palatable if the pension had also been increased for those who genuinely qualify under the revamped tests, and if the superannuation tax concessions, which overtly favour the rich, had also been reduced, simultaneously.

Super concessions cost roughly the same as the aged pension, but are increasing faster. An example of a conspicuous benefit to the rich is the concessional tax on contributions, such that it costs a person on an annual income of $20,000 about $118 to gain a $100 benefit, while it only costs a person on an annual income of $250,000 a mere $62.50 for the same benefit.

A surcharge on the super contributions by the upper income groups would have raised a considerable sum and ensured considerably more equity in the Budget’s treatment of the aged.

In a similar vein, the decision to give universities the capacity to charge course fees would have been more defensible if the government had decided to simultaneously shift overall funding from the universities to students by way of a voucher, thereby enpowering the students to select courses and so driving the universities to compete in terms of both quality and price of the courses offered, only being funded if they are successful in attracting students.

Finally, it is hard to defend the government’s decision to maintain the FBT benefits on cars, again a decision that favours the wealthy, when the previous government was prepared to knock it off, when the government has made a stand against further support for the car industry, and when it would have raised some $1.8 billion.

The Abbott government promised us no surprises but it would be good to have the surprise that they plan to return us to the "land of the fair go."

Dr John Hewson is a professorial Fellow at the Crawford School of Public Policy at ANU and a former leader of the Liberal Party. This is an edited version of his speech delivered at the launch of “Advance Australia fair? What to do about inequality in Australia", a report by Australia21 and the Australia Institute.

How Australia is advancing unfairly

unfair US subsidies and corporate welfare...

After eight decades, the future of the Export-Import Bank is today uncertain. Its charter expires in late September and needs to be renewed by Congress if it is to live on. It shouldn’t. It’s time to pull the plug on the bank.

Ex-Im is the very definition of corporate welfare — it helps foreign buyers to purchase U.S. goods by offering favorable financing for those deals. In 2012, a staggering 82.7 percent of its loan guarantees went to Boeing, as my AEI colleague Timothy P. Carney reported. The government shouldn’t take money out of your paycheck to assist Boeing’s customers.

Not everyone agrees. Some members of the foreign-policy community worry about what will happen when nations buy their airplanes and other hardware from other countries. But surely there are better, more direct ways for the government to accomplish its foreign-policy goals than through an open-ended export-credit agency.

Some argue that the bank creates jobs by gaining more customers for export-based American firms. The case for this claim is weak. The trade deficit and export-based jobs are determined by the savings and investment behavior of American households, firms and the government, and not by trade policy in general, or export subsidies specifically.

How does this work? In the textbook model, when the government subsidizes exports the demand for dollars increases — arising from the need to finance dollar-denominated purchases, bond purchases due to higher interest rates, or other macroeconomic effects — pushing up their price. As the price of dollars increases, exports fall and imports increase. When all is said and done, your export subsidy hasn’t increased employment or really had much of an effect at all on the trade deficit.

read more: http://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2014/06/30/conservatives-against-corporate-welfare-its-time-to-put-this-agency-out-of-its-misery/