Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

when the adults take charge .....

When Robert Menzies won elections, he would reassure voters that he would govern not just on behalf of those who voted for him but also on behalf of those who didn’t. It was a promise to put the national interest above partisan interests and a recognition that almost half of the electorate always votes for the other side.

In his victory speech last year, Tony Abbott repeated Menzies’ promise. A good government, he said, “governs for all Australians, including those who haven’t voted for it”. It has “a duty to help everyone to maximise his or her potential. Indigenous people. People with disabilities. And our forgotten families, as well as those who Menzies described as lifters, not leaners. We will not leave anyone behind.”

At Australian federal elections since 1949 the two-party preferred vote has generally been in the 53 - 47% range. Only in 1975 and 1977 did the winner receive more than 55% of the vote. In 2013 it won 53.49%. But you would think everyone but the greenish luvvies of the inner suburbs had voted for the Coalition by the way the government and its cheer squad at News Corp insist that “the Australian people” have given it a mandate to do everything it said it would and more. Elections are crude and effective devices for transferring power from one political elite to another, but they are not conveyor belts for detailed policy preferences. Voters make their choice at the ballot box for a multitude of reasons, few of which can be pinned to specific policies.

Mandate talk has always been winner-takes-all talk, its main purpose to rub the defeated government’s nose in the loss of rule and give the new government courage to pursue difficult policies. In the first flush of power, the present winners are taking all they can get, including revenge. This is a disturbing shift in elite political culture that makes Menzies’ promise seem quaint.

The revenge is not on the electorate but on the politicians opposite: the members of the previous government and the Greens who supported them, and the union movement with which the ALP is still organisationally entwined. The pathetic Craig Thomson, who has now been found guilty of defrauding the Health Services Union when he was national secretary, will be called before the parliamentary privileges committee to investigate whether he misled parliament when he protested his innocence. The royal commission into union governance and corruption has extraordinarily wide terms of reference to investigate union dealings, including bribes, secret commissions and campaign funds, and without time limits. Julia Gillard’s role in setting up a slush fund for her former boyfriend Bruce Wilson more than 20 years ago will be caught in the trawl, and it is unlikely that Bill Shorten will escape investigation, given his long association with the Australian Workers Union.

Then there is the royal commission into the home insulation scheme that Labor used to stimulate the economy after the global financial crisis of 2008. The scheme, which led to hundreds of house fires and the deaths of four young men, has already been the subject of six reviews, including one by the Australian National Audit Office and inquests by the coronial offices of New South Wales and Queensland. These have concluded that the scheme was too hastily implemented and poorly managed. But the government has decided that working over this fiasco yet again is so urgent that it warrants breaking two of the conventions that keep our politics civilised. The first is that new governments do not launch punitive inquiries into the actions of the governments they have defeated, as the sanctions have already been provided by the electorate in voting the government from office. Malcolm Fraser, after all, did not launch an inquiry into the Khemlani loans affair that brought down the Whitlam government. The second is that cabinet documents are closed for 20 years so that ministers can engage in frank discussion without fear of political fallout. In these conventions, there is human as well as political wisdom. Governing is a difficult and messy business that claims great personal tolls from those who attempt it. Defeated prime ministers and ministers are owed some time out of public scrutiny in which to rebuild their lives and their sense of themselves.

Of course, arguments can be mounted for each of these pursuits, though those for the inquiries into the insulation scheme and now Labor’s National Broadband Network are particularly thin. Abbott claims that all this has nothing to do with payback as he earnestly invokes the rule of law. But there is a pattern, and it is not just the presence of his attorney-general, George Brandis. Craig Thomson, Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard, Peter Garrett, Greg Combet, Bill Shorten, Penny Wong and perhaps more will be called before various inquisitorial bodies to account for things they did or didn’t do.

Whatever the inquiries’ motivations, the impression will be that there are cases to answer, and who knows what will be turned up. Labor will seem like an illegitimate contender for public power, not to be trusted with the reins of government. It all looks very much like a vengeful determination to kick one’s enemies so hard when they’re down that they won’t get up any time soon. It is not quite the same as throwing the defeated opponent into the dungeons, but it has the same motivation.

The winner-takes-all approach is also evident in the attacks on those policies that the Liberals and Nationals regard as emblematic of Labor and the Greens: Christopher Pyne’s establishment of a two-man review of the national curriculum; the unwinding of the Tasmanian forest agreement by attempting to open 74,000 hectares of forest “locked up” by World Heritage listing; the resumption of “scientific” testing of the effects of cattle grazing in the Victorian alpine national park; the jettisoning of (and yet another inquiry into) the former government’s $300 million boost to childcare wages; the stripping of funding from the Environmental Defender’s Offices; the approval of the dumping of dredge spoils in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park to enable the expansion of the port at Abbot Point; the abolition of the Climate Change Authority; the appointment of a Human Rights Commissioner who not only is publicly committed to repealing the section of the Racial Discrimination Act that deals with racially abusive language but also has previously called for the commission to be abolished.

Of similar pattern is the use of the armed services in the mess that has become Australia’s asylum seeker policy, for once the defence force is involved the government and its supporters can invoke its devotion to the nation to put the policy beyond criticism. Take the concerted attack on the ABC for reporting that an asylum seeker claimed to have had his hand deliberately burnt by the navy, which led to Prime Minister Abbott accusing the broadcaster of “taking everyone’s side but Australia’s”, or the abuse that rained on the head of ALP senator Stephen Conroy when he accused Lieutenant General Angus Campbell, the commander of Operation Sovereign Borders, of being engaged in a political cover-up. Conroy was rude and his motives questionable, but his accusation was half right. Campbell and his fellow officers are not intentional agents in a cover-up, but there is no doubt that the government is hiding behind the military’s near-immunity from public criticism to deflect public scrutiny of Operation Sovereign Borders.

It is not good for democracy to hold the military beyond criticism. It is not even good for the military, for it discourages the robust criticism needed for it to remain at its best. Events are proving a case in point, particularly in regard to our navy, whose navigational expertise and equipment are so poor that it is reportedly unable to detect Indonesia’s sovereign sea border, and half of whose patrol boats are presently docked for structural repairs.

Being prime minister is about managing the dialectical interplay between division and unity, between pushing one side’s special interests and managing the diverse interests of the country as a whole. Abbott is trying. His serious demeanour and studied, rather ponderous public utterances seem like those of a man keeping himself in check, restraining his pugilistic instincts in order to appear calm and reasonable, there for all Australians as he promised on election night. As well, he now has real and difficult problems to deal with, such as managing the consequences of the end of the car manufacturing industry, the decline of Qantas, an unemployment rate edging in the wrong direction, and our deteriorating relationship with Indonesia.

But too many of his government’s actions are telling a different story: that of a bunch of winners taking it out on the losers, as if the country were divided along the same lines as the parliament. It all feels a bit like student politics in its short-term point-scoring, its payback and its intense personal antagonisms – yet another episode in the increasing disjunction between our adversarial parliament and the complex diversity of experience and opinion in contemporary Australia.

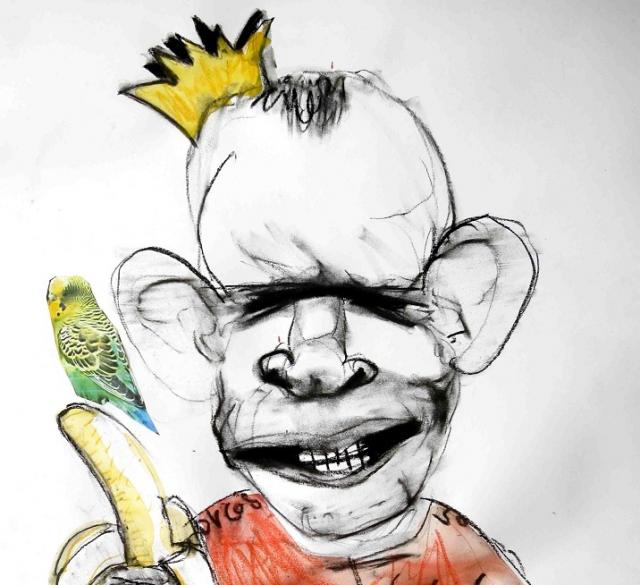

The Triumphalism Of Tony Abbott - The Liberals' Winner-Takes-All Political Payback

- By John Richardson at 31 Mar 2014 - 6:27pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

12 hours 11 min ago

12 hours 14 min ago

13 hours 14 min ago

15 hours 17 min ago

15 hours 58 min ago

18 hours 22 min ago

19 hours 42 min ago

19 hours 49 min ago

1 day 4 hours ago

1 day 5 hours ago